Another Man Nobody Knows

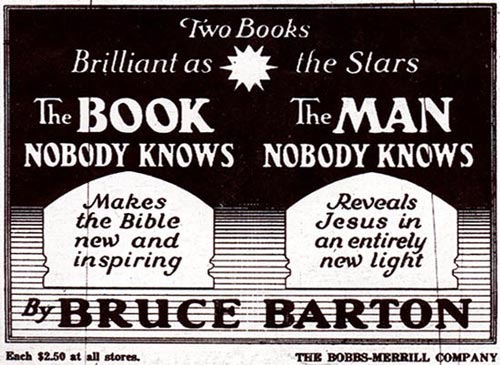

There’s another man that nobody knows about – like William Dean Howells – and I think I can make a case for why he should find a place in Major Problems. And that man is Bruce Barton.

|

| Betty Crocker ad, c. 1927 |

Barton gained widespread popularity in the mid 1920s for his book The Man Nobody Knows. It was a new spin on an old man: the “late, great Jesus Christ,” as one of my former students always put it when discussing religion or Christianity. Hist discusses Barton as part of the 1920s culture of consumerism and especially its new emphasis on advertising. And Barton was a pioneer in the advertising world. He helped establish an advertising firm just before 1920 and then created the character of Betty Crocker.

When it came to Jesus, Barton was fed up. He was tired of the Christ he encountered at Sunday School as a child. There, “Jesus was the ‘lamb of God.’ … [H]e sounded like Mary’s little lamb. Something for girls – sissified. Jesus was also ‘meek and lowly,’ a ‘man of sorrows and acquainted with grief.’ He went around for three years telling people not to do things.” This wouldn’t fly in the 1920s. The meaning of Christ for the modern age was profound: “He picked up twelve men from the bottom ranks of business and forged them into an organization that conquered the world.” Jesus was an “executive”, an “outdoor man,” a “sociable man,” and he taught how to advertise. Jesus “recognized the basic principle that all good advertising is news.” He was, Barton concluded, “the founder of modern business.” (I won’t mention it here, because Paul Harvey and I have now entered the copy-editing stage for our book on race and images of Jesus throughout American history, but Barton had a lot to say about what Jesus looked like and how he has been portrayed in artwork; more on that soon in Jesus in Red, White, and Black).

|

| <http://xroads.virginia.edu/ ~ug00/lambert/rb/bartonadbig.jpg> |

As the chapter on the 1920s in Major Problems reads now, it includes religion beautifully. There is a great cartoon of the evils of modernism; there is a radio broadcast calling Americans back to Jesus and traditional ways; and there is an incredible excerpt from Darrow interrogating Bryan. And heck, one of the historical essays is from Edward Larson’s amazing book Summer for the Gods. But while these documents may show the cultural rifts of the 1920s and the emergence and shaping of Fundamentalism, they do not set up the Great Depression – and that’s what Barton accomplishes.

Barton’s The Man Nobody Knows shows how committed Americans were to market capitalism and the culture of affluence. It shows how far their intellectual and religious worldviews were permeated by materialism and material growth. Only four years later, when the Stock Market plunged in 1929 and the economy spiraled out of control, Americans experienced it not as another example of hard times (like the ones they experienced during the Gilded Age). They took it as a shock; it struck to their core as if they had never been poor or out of work before. Bruce Barton helps set our students up for the great fall. And then … then we can understand how in the 1930s, W. E. B. Du Bois had a new Jesus character say in a new Sermon on the Mount, “there won’t be any rich people in heaven” or John Steinbeck could give the former-preacher-turned-radical-labor-organizer the name Jim Casy (note his initials).

Here’s a vote for Bruce Barton and The Man Nobody Knows getting greater play in the 1920s. Not just to epitomize the era, but to prepare us for what’s next.

I would agree to include Barton in Major Problems. I noticed while reading M.P. that it seems to be a one-sided, traditionalist view on religion and returning to the roots. Barton would spice up by bringing in a business-Jesus viewpoint. Also I never really connected why there wouldn’t be a sense of shock and that people should have remembered of the economic conditions of the Gilded Age. I feel that as soon as people get the money, they acclimated so quickly to the newfound benefits of affluence that they were blindsided by the sudden end of their new lifestyle. Once again, this would be a valuable addition to Major Problems to make it more rounded.

The document I will be discussing is from chapter 7 document 6, “Margaret Sanger Seeks Pity for Teenage Mothers and Abstinent Couples, 1928.”

After reading this document I was so relieved that I did not grow up in this time era because I would be really mad if I got married at 12. Women were treated like pets that were to work in the household and have children, never free to live out their dreams in life. One woman said, “I am seventeen years old. I married when I was thirteen years old and I am a mother of six children.” I am 18, I have no children and do not intend to for a long time. Did these women feel the same way? This was 80 years in the past so maybe this is what they want because they grew up in that culture.

Kelsey Rodocker

I will be discussing the seventh document from chapter 7 titled, “The Automobile Comes to Middletown, U.S.A., 1929”. The document states the the “first real automobile appeared in Middletown in 1900”. Within 20 years there would be 6,221 passenger cars in the city. As bad as this sounds, I did not know cars were around that long ago. I could only imagine the wealth and symbolism associated with owning or riding in a car at this time. The thought of not having a car, and the freedom and fun that comes with having one, is one that I could not cope with to be completely honest. Cars have become such a necessity and way of life, it just simply seems weird to me without them. Besides, using horses for ways of transportation seems awfully smelly. Was it cars that were the first thing to allow teenagers to start wanting freedom and breaking away? I wonder how much a car would have cost then, in relation to now?