Religion, Religions, Religious, and Native Americans in Colonial America

1) What drew you to colonial American history and to Native American religions?

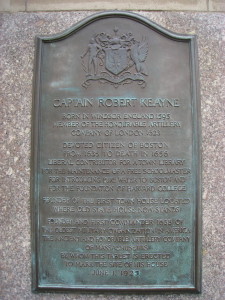

I recently came across a hand-written sheet of paper (remember those?) from 2001 on which I had listed out potential dissertation topics should I happen to get admitted into a Ph.D. program. The list is pretty entertaining, but in retrospect, one of the twenty or so ideas was eerily prescient: “Evangelization of Native Americans.” But that wasn’t really where I was intellectually at the moment. I was admitted to Harvard to study late nineteenth / early twentieth century social reform and was hoping to build on my M.A. thesis on the settlement house movement (the thesis looked at Robert A. Woods and Boston’s South End House). In my first semester I took a “Radical Religion” seminar with David D. Hall—essentially a research seminar on transatlantic puritanism—and by the time I had handed in my final paper on Robert Keayne and the issue of usury in early Boston, I knew I was hooked on the colonial period. I dabbled for a while in transatlantic Puritanism but eventually realized that, no matter how much I was trying to focus on Puritans, Native Americans were omnipresent in ways that I couldn’t quite explain or understand. So I began to read widely in the literature on American Indians in the colonial period and soon realized that the period after King Philip’s War was this historiographical black hole, until the First Great Awakening, that is, when particular Native groups in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and on Long Island, suddenly reappeared long enough to convert en masse in the revivals. I wanted to know what happened to these groups between the 1670s and the 1740s and why they chose to convert so suddenly and completely in the Awakening. Despite being told by some well-meaning folks that there simply wasn’t enough out there to sustain a dissertation, once I started researching and writing I was amazed at how much I had from which to draw. Although the dissertation only went up to the 1780s, for the book I continued the story up through the 1820s, but in reality there is no real “ending” for Native religious engagement. What I found was that while the Awakening was one important season of religious engagement, it alone does not adequately capture the complicated ways in ideas about religion intertwined with concerns over land and community sovereignty. And, the narrative about “sudden and complete conversion” in the Awakening was wrong, by the way.

I recently came across a hand-written sheet of paper (remember those?) from 2001 on which I had listed out potential dissertation topics should I happen to get admitted into a Ph.D. program. The list is pretty entertaining, but in retrospect, one of the twenty or so ideas was eerily prescient: “Evangelization of Native Americans.” But that wasn’t really where I was intellectually at the moment. I was admitted to Harvard to study late nineteenth / early twentieth century social reform and was hoping to build on my M.A. thesis on the settlement house movement (the thesis looked at Robert A. Woods and Boston’s South End House). In my first semester I took a “Radical Religion” seminar with David D. Hall—essentially a research seminar on transatlantic puritanism—and by the time I had handed in my final paper on Robert Keayne and the issue of usury in early Boston, I knew I was hooked on the colonial period. I dabbled for a while in transatlantic Puritanism but eventually realized that, no matter how much I was trying to focus on Puritans, Native Americans were omnipresent in ways that I couldn’t quite explain or understand. So I began to read widely in the literature on American Indians in the colonial period and soon realized that the period after King Philip’s War was this historiographical black hole, until the First Great Awakening, that is, when particular Native groups in Connecticut, Rhode Island, and on Long Island, suddenly reappeared long enough to convert en masse in the revivals. I wanted to know what happened to these groups between the 1670s and the 1740s and why they chose to convert so suddenly and completely in the Awakening. Despite being told by some well-meaning folks that there simply wasn’t enough out there to sustain a dissertation, once I started researching and writing I was amazed at how much I had from which to draw. Although the dissertation only went up to the 1780s, for the book I continued the story up through the 1820s, but in reality there is no real “ending” for Native religious engagement. What I found was that while the Awakening was one important season of religious engagement, it alone does not adequately capture the complicated ways in ideas about religion intertwined with concerns over land and community sovereignty. And, the narrative about “sudden and complete conversion” in the Awakening was wrong, by the way. 2) In one of the “Major Problems in American History” essays, David Hall discusses the “enchanted worlds” of colonial Americans. Did those enchanted worlds change during the eighteenth century and did Native Americans participate in those enchanted worlds?

Although I love Worlds of Wonder, I have long found that colonial Americans continued to live in enchanted worlds, despite the apparent breakdown in the sharedness of this world in the early eighteenth century between educated elite leaders and the people in the pew. Even more, history has a funny way of moving in cycles; fast forward another hundred years and, immediately following a supposedly “secular” phase of American history—i.e., the decade or so immediately following the American Revolution—suddenly you have massive revivals breaking out in Kentucky, Virginia, and eventually New York and New England. I increasingly believe that there have always been portions of American society who live in “enchanted worlds” – both in the eighteenth century and now (the rise of global Pentecostalism and the Charismatic movement attest to the ongoing power of enchantment today, I think). In the colonial period, many Natives fell in the “enchanted world” camp. Some of this was due to their pre-contact beliefs and practices that lent themselves to reading divine or supernatural causes to illness, weather changes, and other inexplicable events (much like the worlds of wonder Hall describes). Doug Winiarski has a great essay, “Native American Popular Religion in New England’s Old Colony, 1670–1770,” which illuminates some of this belief among Natives post-contact. But even among Natives who could be seen as “New Light” in orientation, belief in an enchanted world abounded. The Mohegan Joseph Johnson noted that on December 22, 1771, all those in his uncle’s house heard an “Uncommon noise, as if one Struck with all his might upon the housetop,” once in the evening, and twice more at daybreak. Just the day before, a large black spot “about the bigness of an half Copper” appeared on the palm of the hand of Johnson’s aunt, which stayed for a while, then vanished, but left her with “a strange sort of feeling after Some time.” “What can be the meaning of these,” Johnson pondered, “we must leave to time to determine.” The question was not whether there was meaning in such events, but what that meaning was.

(part 2 will be posted on Friday so we can all have something to chew on for the weekend)

Great stuff here, gents, and I have a question: I too “have always loved World of Wonder, but…” And for the same reasons you cite. These worlds of wonder don’t seem to go away.

Perhaps they are recasted from “acceptable” to “unacceptable but still prevalent.” Because you’re the expert, Prof. Fisher, I wonder what your take on this is? I’m teaching the Second Great Awakening right now and having to explain seer-stones, treasure digging, and the like, much less Angel Moroni and the Kingdom of Matthias. Is there something special in the colonial era?

Wouldn’t one of the big differences be who is believed and by whom? In 1692, authorities believed Tituba and the others called to testify. In Matthias’s trial, the judge didn’t believe he actually had any spiritual insight. Most Americans did not follow Joseph Smith, while in the time Hall wrote about, it was leaders and powerful figures who held these values too. A world of enchantment continued and continues, but the point seems to be that it was less and less socially potent (or perhaps became only socially meaningful for particular people).

Cotton Mather, for instance, when chronicling colonial history was happy to invoke supernatural forces invading this world in everyday affairs. George Bancroft then in the mid 19th century certainly had a providential interpretation of history – God was using American democracy for his grand purpose – but he didn’t see imps leading John Calhoun.

Outstanding work Lin and kudos to the blog for taking up this topic!! My own research about Catholics in the 21st century takes up the topic of continuing attractions to “presence” rendered in ways considered outdated after the Second Vatican Council. Comparative enchantments seems a promising topic for scholarship and teaching.

Excellent discussion here. Glad to see that Lin’s work will be coming out soon.

Hey all, great discussion; sorry to be a latecomer. I wonder if it isn’t helpful to separate “worlds of wonder” from belief in the supernatural. Although the phrase “worlds of wonder” has demonstrated tons of elasticity in what it covers, I think part of what David was really getting at is literally this wonder at things that seemingly had no natural explanation. And perhaps it was this wonder that was lost–in the instance of Increase Mather and his change over time in how he viewed comets, not as examples of wonder but ordinary occurrences within our solar system. But even things that had natural explanations could be considered supernatural in their timing, long after the worlds of wonder were “gone.” Read this way, seer stones and treasure digging, along with healings and fainting in the spirit, speaking in tongues, and even Catholic presence post Vatican II are part of this extra-natural realm that is still slightly different from the 17th c. worlds of wonder. But perhaps that is splitting hairs. Someone needs to invite David to the conversation! On the issue of acceptable vs. unacceptable but present, the question is always acceptable to whom? In every century between the 17th c. and our own time you will always find leaders of movements or even who are prominent members of society who approve of whatever activity is taking place or supernatural beliefs are being expounded, even if others find it unacceptable. And that raises a huge question about whose religious authority holds sway, both at the time and in our own estimation (even though we think we don’t think about such things in this way). And I don’t think the divide is always between the educated and the uneducated or the elite and the commoners, although sometimes those divisions do hold true. Well, anyway–no real answers here, but I look forward to continuing to puzzle over these things with you all.

Prof. Fisher,

Thanks for the response. And I agree, I think, but am still curious about the meaning of “wonder.” For instance, I, more often than I should admit, wonder how it is that Ed Blum has so many friends. As you say, there is really no natural explanation. And yet… But in a more serious vein, the Enlightenment does much to disenchant the world but so much of what it means to be religious resides outside Enlightenment ideals, especially in colonial America and the United States. Thus I’m stuck in this circular kind of debate about “wonder” and what’s changed…

But I do think you are exactly right to point out that who controls the boundaries of “acceptable” vs. “unacceptable” is the key point, and perhaps a useful way of understanding the American religious past is to probe constantly who it is that controls the boundaries. How do they do it? Why? To what end? And were they successful? As a scholar of the Christianization of Native America, you’re in a useful place to put forward some answers regarding the colonial period!

Thanks again for sparking all these thoughts.

Kevin