I was reading Anthony Grafton’s review of Andrew Delbanco’s new book, College: What it Was, Is, and Should Be, and was thinking about a question that constantly lurks in the back of my mind as I teach:

What do I need my students to leave this class with?

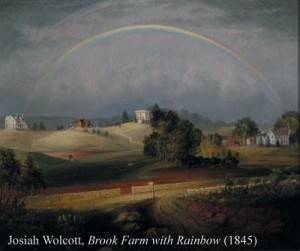

For example, one morning I read in the New York Times a David Brooks column where he had a throw-away line along the lines of: “If you go to college and don’t know the critique of industrial capitalism brought forward by the Transcendentalist, then your education wasn’t worth a damn.” Sometimes I actually agree with David Brooks, and this was one of those times. That very day I taught a longer section than planned on the Transcendentalists. Perhaps Jackson’s war on the banks got less time than it deserved, but, at the end of the day, having my students know the Transcendental critique of capitalism was far more important than having them know the insides and outs of the Biddle-Jackson bank battle.

The rise of fundamentalism and bibilical literalism are other examples of events that maybe weren’t the most recognized of the era, but I really wanted my students to know about it. It affects their lives to this day.

What else gets mentioned? The Southern strategy, the white ethnic revival of the 1970s, the Populist and Labor Movement critique of the industrial order.

I guess at the end of the day I want them to learn at least two things: (1) the world is not preordained but was created among a range of options; and (2) what those options were (and are) so they can have tools in their intellectual quiver. This is different from the uncoverage method of teaching that I’ve blogged about. But it is really what we’re all after, no?

Or am I wrong? Or should I be stressing other things?

didn’t we establish that the only thing students needed to know about was the Populists? 😉

Tariff policy, Kevin. Tariff policy.

More seriously, I think you should emphasize the things that you are most passionate about. At the end of the day, in my judgement, students remember what you teach passionately, and the rest vanishes about 1 day after the semester ends, if it was ever there to begin with.

Paul,

Great point. And I guess in a roundabout way that’s what I’m saying. I am terrified by the prospect of, say, unfettered capitalism and what it does to a perceived larger “common good,” and I am painful aware of the persistent racism in American life. So one way to read my entry is as a commentary on what I find important. I would be curious to know what others think is important. Tariff policy? The Bank War? The United Nations?

Kevin

Hi all. I’m fairly new to the blog, and first time commenting. Kevin, I actually think your question fits nicely with the uncoverage model. At least one of the texts recommended by advocates (Fink, Designing Significant Learning Experiences) says we should link learning goals to our own dreams for what students will know/be able to do after the course is over. If the course is set up to help students uncover the Transcendental critique, rather than have you simply tell them about it, it’s uncoverage. It’s set up with a larger question/problem rather than just the topic — is the particular kind of capitalism that developed inevitable? Were there alternatives? Are there still?

One of my own is for students to see that Americans tend not to be particularly pure about being “big government” and “small government” on the ground — preferences change depending on circumstances, and individuals/groups/parties switch sides depending on the issue because other priorities have driven expectations of government. So we read about the Fugitive Slave Act/Personal Liberty Laws, then we get to secession and emancipation and Reconstruction and some eyebrows go up. Same with land give-aways to railroads and minimum wage/working condition laws, and with various realms of social and economic legislation more recently, etc. Students end up asking/thinking about why Republicans and Democrats (or groups within) seem to switch sides on the “big government” question. One hope is that in a few years when they hear someone say “That’s bad because it’s big/small government,” or some nonsense about how it’s always been, they’ll think “wait a minute” and actually think through the issue rather than rely on the short-hand.