We live in a great age of visualization. Plummeting bandwidth restrictions and the growing availability of high-resolution images (owing in part to the advances of Wikimedia, Flickr, and other open image databases) have antiquated the pixelated images found in five-year old PowerPoint slides. YouTube, digital movie files, and a rapidly multiplying cache of fantastic visualization and digital reconstruction projects, meanwhile, are allowing students to immerse themselves in lost worlds. The nineteenth- and twentieth-centuries in particular, with their rich and often overwhelming number of photographs, lithographs, graphic arts, and material objects, are particularly rich with visual resources. Without such rich visual reserves, however, great swaths of early American history seem to languish in vast visual deserts.

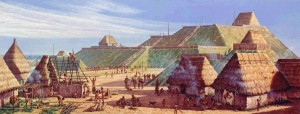

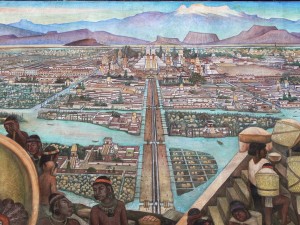

The problem is especially acute for America’s pre-historic native cultures. Consider Cahokia, the sprawling Mississippian city near present-day St. Louis that rivaled anything seen north of modern-day Mexico until the nineteenth century. With enormous mounds, extensive trading networks, numerous dwellings, huge palisades, and extensive corn fields, Cahokia’s full awe-inspiring reality seems confined to a few images taken from National Park Service displays. Or consider Tenochtitlan, the Aztec’s fantastical lake city that rivaled anything contemporary European cities offered in size or grandeur. Bernal Diaz del Castillo recounted the dumbstruck Spaniards’ first glimpse of the city in his Conquest of New Spain:

When we saw so many cities and villages built in the water and other great towns on dry land … we were amazed and said that it was like the enchantments they tell of … Some of our soldiers even asked whether the things that we saw were not a dream … I do not know how to describe it, seeing things as we did that had never been heard of or seen before, not even dreamed about.

And yet Tenochtitlan, too, is visually handicapped. Those desperate for high-resolution visuals seem confined to blurry shots of Diego Rivera murals, shots of bland museum models, or the sensationalistic (yet still pedagogically useful) paintings of Emanuel Leutze and early Spanish chroniclers. One can read of Tenochtitlan’s wonders, but not see them.

Much of European colonization remains as visually starved as native American cultures. Aside from several romantic National Parks Service paintings and contemporary maps and sketches, Jamestown lacks the high-definition and interactive visual treatment worthy of its massive historical weight. Virtual Jamestown, for instance, offered an interactive tool for the late-90s, but what has risen to replace it? For now, perhaps contemporary sketches, real-life reconstructions, and clips from Terence Malick’s visually stunning (and openly myth-embracing) The New World suffice.

Even for those pieces of early American history rich in visual imagery, modern digital reconstructions offer a promising yet frustratingly under-developed path toward visual immersion.

At its best, digital reconstructions could provide glimpses into the bustle of Cahokia, the wonders of Tenochtitlan, or the squalor of Jamestown. For instance, donors recently KickStarted a promising effort to produce an immersive 3D digital recreation of a Bronze Age village in England using geographic and archaeological data. Several similar projects already exist for North America. In 2009, for instance, the Imaging Research Center at the University of Maryland, Baltimore County produced an impressive high-definition recreation of Washington D.C. as it would have appeared in 1814. A much older (and therefore inevitably less visually impressive) effort similarly attempted to give life to the ruins of Chaco Canyon.

The continued development of visually sophisticated digital reconstructions, along with the continued production and dissemination of high-resolution images and video, can only help to more fully immerse students in the past. Meanwhile, there are inevitably many worthy projects trapped in obscurity and others that are widely used yet still unknown to many. So what are they? What do you use to capture the lost visual worlds of early America?

Check out CERHAS at the University of Cincinnati. They have done extensive recreating prehistoric Native American architecture. Also check out ancient ohio trails for a real world application

Wow! Great stuff here. Thanks for putting the information and the links on the site.

For the Aztecs, I’ve used the Historia general de las cosas de nueva España (General history of the things of New Spain) by Fray Bernardino de Sahagún, also known as the Florentine Codex. I realize it falls under the category of Spanish chroniclers, but Sahagún’s visuals are equally stunning and evocative of Aztec culture. The whole set is available in a digitized version from the World Digital Library.

Great post. Have you considered using SketchUp to render certain historical buildings or sites for teaching purposes? It’s incredibly easy and makes it possible for even us non-computer science types to create 3-D architectural models at zero cost. Additionally, to add to the list of rendered historical sites, have you seen this rendering of the Chicago Exposition of 1893? It’s not available online, but looks to be amazing. http://www.msichicago.org/whats-here/tours/two-ways-to-tour-the-white-city/