In the spirit of continuing my week of post-conference active learning to stave off end-of-term slacking (theirs AND mine)… here’s another one that worked especially well this past week. I should explain – many of my non-lecture lessons are done off the cuff, “just in time,” or slapped together at the last minute (choose your metaphor), so I’m pleasantly surprised at those that don’t flop; I can use them again. Come to think of it, if I were a quarterback (or a brilliant church nursery leader) I might actually write them on my cuff.

The textbook I’m using this term has documents clustered on a theme in each chapter. For the chapter on 1980s conservatism, the theme is affirmative action, with a range of views. This is a topic which could get abstract and opinionated real fast, so my goal was to keep bringing students back to the evidence. I was thinking of Joel Sipress‘s advice in the “Signature Pedagogy for the Survey Course” workshop I attended at the OAH: helping students move from “truth is fixed” to “truth has 31 flavors, all equally good” to ” we can have a shared basis for judgment between what makes one argument better than another.” He also reminded us that in history, the shared basis is the extent to which an argument is consistent with the evidence about the past; i.e. evidence is our standard of judgment – it IS the criteria (not just an ingredient). I found this to be a super-helpful takeaway among many from that awesome session. But I digress.

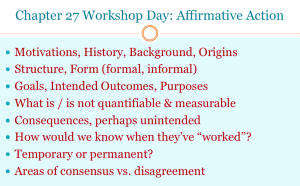

I decided to run a full-class discussion, since we do a lot of small group work on our document workshop days and I wanted to change it up. This took the form of a giant think-aloud on how to construct a historical argument and use evidence as the basis for deciding among possible hypotheses.

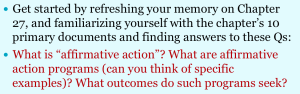

First, I had them read/review the chapter’s documents and identify the range of viewpoints and for each one, performing some of the primary source critical thinking we have done all semester (genre, audience, language, structure, author, date… etc..)

Next, we made sure that we all understood the terms, concepts, and historical background of this debate with some discussion, opportunity for questions, defining words, etc.

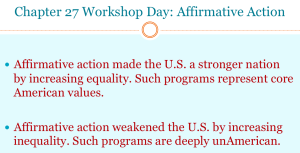

Then, we explored two possible interpretations that seem (on the surface) to be mutually exclusive. Some documents supported one, some supported the other.

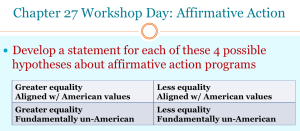

I pointed out that the two second sentences in each statement could actually be swapped, giving us four possible hypotheses to play with.

Now, the part that feels like work: as a class, we hammered out four sentences, each expressing one of those hypotheses in a single concise statement. This is what we came up with (as raw, student-created statements, these are a little rough, but it was enough for our purposes… you might notice we were least successful with the one in the lower left of the quadrant):

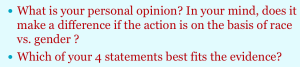

Lastly: this final part is very important, because one thing that beginning history students find hard to do is disentangle their own beliefs, presumptions, and opinions from the actual evidence (come to think of it, this is hard even for non-novices). Without a show of hands, I asked students to first decide which of those four sentences they personally agreed with the most, or which aligned with their own values most closely. Then … I asked them to decide which one best fit the evidence.

This was the aha moment for me, and I hope for them as well, to see that those might be two different possibilities. Incidentally, we found statement #2 to best fit the evidence provided for us in the document section. In breaking down the process in this way, my hope was that students began to recognize that given a different set of evidence or a different question, other hypotheses might be considered. In other words, historical truth is not only “not fixed” but actually contingent upon the evidence itself – an insight that is actually one of the outcomes for my whole course. This lesson turned out to be a really useful way into that concept, I will definitely do something similar again; I can also imagine adapting this up to a slightly more sophisticated level into a writing exercise for the methods course, or a peer review session for the senior seminar.