Goods and the Good

Here is part 2 of our interview with Professor Linford Fisher. He discusses the kinds of primary sources he likes for the classroom and how to integrate commercial history with religious history in the colonial period. I also want to draw your attention to his marvelous historiographical essay on “Colonial Encounters” in The Columbia Guide to Religion in American History. Our many thanks to Professor Fisher and we’ll have more on his book in September!

I’ve always found it effective to use the list of grievances King Philip gave to John Easton in 1675. It opens up space to talk about the issue of Native perspective on colonial events (like warfare) as well as the thorny issue of authenticity in terms of Native voice. But the grievances are clear and also lead to a conversation about dispossession, livestock, and unwanted evangelization. See John Easton, “A Relation of the Indian War” in A Narrative of the Causes Which Led to Philip’s Indian War (Albany: J. Munsell, 1858).

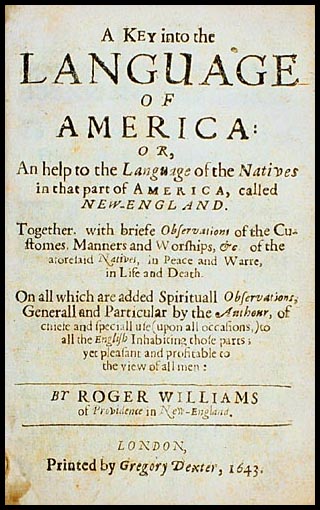

Another source I think is rich and underutilized is Roger Williams, A Key Into the Language of America (1643). It is one of the very few ethnographies—even if clearly biased—from the English in the early decades of colonial settlement. It is rich and full of description that truly illuminate. I found myself returning to it repeatedly when writing the first chapter to my book and enjoying it quite a bit. Although it is too long to assign as a whole, you can easily select certain chapters and talk about Native practices and beliefs on a variety of issues. And the little moralizing poems naturally raise the question of bias and English views of Native cultures. But again, of course I think we need to read Williams critically and with both eyes wide open.

Another source I think is rich and underutilized is Roger Williams, A Key Into the Language of America (1643). It is one of the very few ethnographies—even if clearly biased—from the English in the early decades of colonial settlement. It is rich and full of description that truly illuminate. I found myself returning to it repeatedly when writing the first chapter to my book and enjoying it quite a bit. Although it is too long to assign as a whole, you can easily select certain chapters and talk about Native practices and beliefs on a variety of issues. And the little moralizing poems naturally raise the question of bias and English views of Native cultures. But again, of course I think we need to read Williams critically and with both eyes wide open. 4) Another “Major Problems” essay by T. H. Breen focuses on the role of commodities and consumer goods in tying the colonial world to that of Great Britain. How did consumption or consumer practices influence Native Americans (if at all)? Did it impact their religion or religions?

Ironically, at least early in the colonization process, it would be more accurate to say that commodities and Native goods tied Europeans to the Americas, although certainly later the balance of dependency shifted in favor of the Euroamericans. North America had beaver pelts, deerskins, furs, and wood (especially important for the denuded English landscape); South America and the Caribbean had a bewildering variety of new food items that Europe hungrily adopted, such as potatoes, tomatoes, coca beans, and corn, along with tobacco and of course silver and gold. But Natives were affected by this trade and extraction. Not only were entire Native civilizations demolished, but sacred landscapes were changed. Scholars continue to find immense interest in the ecological changes triggered by land-clearing, deforestation, and beaver hunting instigated by the colonists. But Natives were also affected by the material trade and consumer goods themselves. James Axtell speaks of the “first consumer revolution” (echoing the eighteenth century one Breen writes about) that took place in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as Natives slowly incorporated copper pots, steel knives, guns, blankets, shirts, steel hoes, metal awls, paint dyes, alcohol, and even mirrors into their everyday lives. One of the biggest cultural costs of these new technologies was the long-term loss of more traditional ways of production, which, in turn, led to an increased dependence on a steady flow of European trade goods.

|

| bear paw |

In terms of religion, one of the biggest ways we can trace the effects of this influx of consumer goods is through funerary objects in Native graves. One of the most poignant examples of this comes from a late seventeenth century grave at Mashantucket, Connecticut. In a young teenage girl’s grave, amongst the more traditional funerary items such as a pestle and beads archaeologists in 1990 found a medicine bundle that contained fragments of a Bible page and a bear paw. I wrestle with the meaning of this a bit in the introduction to my book, but it seems to me it is a clear example of how the physical presence of the Bible and the teachings contained in it had become part of funerary practices and—perhaps equally as important—one additional potential means for providing in the afterlife or a deceased relative. But even more broadly, the educational and evangelistic efforts made by the colonists in Native communities meant that in churches and schools Natives were presented with an astonishing array of new material goods, such as all kinds of books and primers, inks and quills, eyeglasses (for reading), benches and tables, and European clothing and foods.

5) What’s your favorite essay or book on early America?

I love Alison Games’ Web of Empire. It, more than any other book out there, I think, succinctly and effectively places colonial America in its rightful Atlantic and even global context. Atlantic history is still alive and well, I think, but the more creative scholarship seems to be moving in an ever-expanding transnational direction, all of which makes it daunting to keep up with the scholarship, let along contribute to it along these lines. For undergrads, I’ve found Patricia Seed’s Ceremonies of Possession does some of this same work, although in different ways. More strictly related to “traditional” colonial America, I’d have to say a favorite is Jill Lepore’s The Name of War. She’s a terrific writer and this book is witty and informative, as well as broad-ranging. I find myself returning to it when I need some writing inspiration.

Excellent interview. I remember reading Jill Lepore’s “In the Name of War” when I took a course on early America taught by Laurel Thatcher Ulrich. An astonishingly rich and fascinating book. Also one of my favorite books on this topic. So glad to see the second part of Lin’s musings on colonial encounters and Native American cultures.