Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter failed at the box office. I haven’t seen the movie (I’ll rent it for $1.31, unless redbox’s prices jump again), but I did read the novel. In part, I grabbed it because a group of junior high and high school teachers told me their students were reading it. I enjoyed Wicked, The Hunger Games, and the Dan Brown novels so I thought – why not. ALVH is not an awful read; it takes one through the first sixty years of the 19th century ok. And we meet many of the main characters from the age.

Abraham Lincoln, Vampire Hunter failed at the box office. I haven’t seen the movie (I’ll rent it for $1.31, unless redbox’s prices jump again), but I did read the novel. In part, I grabbed it because a group of junior high and high school teachers told me their students were reading it. I enjoyed Wicked, The Hunger Games, and the Dan Brown novels so I thought – why not. ALVH is not an awful read; it takes one through the first sixty years of the 19th century ok. And we meet many of the main characters from the age.

So why, as a historian, did I feel mad at the end of it? Because it could have been better fiction if Seth Grahame-Smith had spent less time googling and wikipedia-ing (two sources he thanks in his acknowledgments) and more time talking to an actual historian. If he did, he would have had more to add to his fun. Such as:

- Jefferson Davis attended Transylvania University in Kentucky. Why not have him meet vampires there???

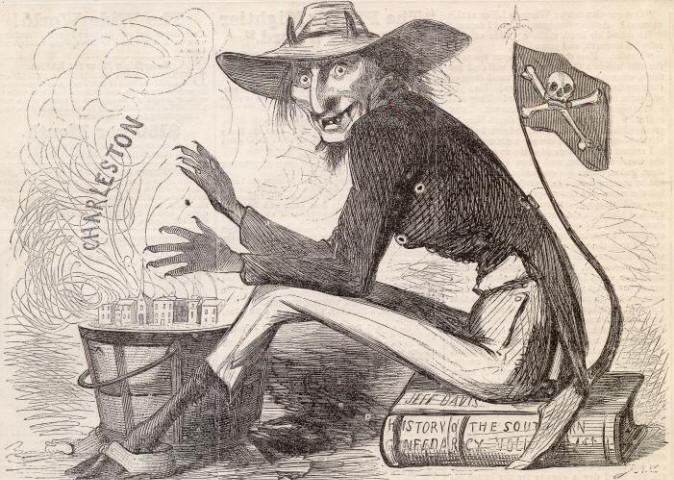

- Political cartoons from the era had vampiric characters (so SGS would not have had to use the ridiculously photo-shopped images he used).

- He might have found a way to include an African American character (maybe Harriet Tubman) as a vampire hunter too. This would have offered at least one black character with an actual … character.

|

| Harper’s Weekly, 1862 http://www.sonofthesouth.net/leefoundation/ civil-war/1862/january/jefferson-davis-devil.htm |

This comment has been removed by the author.

I haven’t read the book or seen the film (I read “Pride and Prejudice and Zombies” and found it tiresome about halfway through) but I believe Harriet Tubman is in the film. Though, she may be a fairly minor character…I’m still astounded that John Brown is not a character in Grahame-Smith’s story. I mean, here is a historical figure who really did go around “hunting” pro-slavery opponents and hacking them to pieces (I know the historical narrative is more complicated than that, but you get the point)and spoke in dramatic Apocalyptic language about blood about as often as most people talk about the weather. There’s even a song about his corpse a-moldering in the grave while his soul marches on!

Sigh. Missed opportunities. Maybe I’ll self-publish a fan-fiction e-book about Brown and become fantastically rich. Wonder if that will count for tenure…?

I have not seen the movie … but yeah, looks like they were smart enough to get Harriet Tubman in there. And yes, John Brown would have been a natural for the book/film as well. The book offers a disturbing approach to US history in the Civil War: white people act upon black people … either as vampires, as pawns of vampires, or as liberators of them and killers of vampires. Any way you slice it, the passivity and lack of individuality among African Americans in it is frustrating.

I’m an English teacher and a Holocaust scholar (and a friend of Carson’s, which is how I found you). These musings interested me.

I get into a lot of conversations with a lot of people (mostly high school kids) about the historical accuracy – or decided lack thereof – of the novels we read (I’m really an English teacher who’s also a frustrated history/civics teacher). While I am often much more satisfied when the novels I read (and the movies I watch) have a basis in reality, I’m not as put off by those that don’t, and here’s why: MY thinking is that an important part of my work is to inspire curiosity in my students. If I can get a kid to do a little more digging into the “real” history behind the stories that we read or watch by letting them know that what happened in the novels or films wasn’t what really happened, then I’m going to do that. That may be where the real value of those inaccurate stories lies.

For example, I engage in a regular discussion (read, “argument”) about Mel Gibson’s Hamlet. I teach it all the time; I think it’s a great way to get kids engaged in a complex and, at times, difficult text. A friend of mine rails against me for this EVERY SINGLE TIME, claiming the film an abomination and arguing that Gibson, along with his many other failings, couldn’t even bother to keep the scenes in order.

Is my friend wrong? No; but I still teach the film because the kids RESPOND to it. It is a doorway through which I can lead them into a more careful – and more accurate – study of the themes and ideas (and the Bard’s actual play). I feel the same way about some of the films about the Holocaust that the scholarly community disdains. I’m not strictly looking for stories that are going to teach the history; my focus is much more on the human emotions and the themes and ideas that I can mine from those stories, and the ways in which I can get the students to apply them beyond the literature in question.

That doesn’t mean that I’m willing to abandon all sense of honoring the truth of the past, certainly, but I do see a great deal of value in piquing kids’ interest. If this film gets even a couple of young people interested in reading more about Lincoln or the Civil War from accurate and reliable sources (toward which it is our job to steer them), is that enough?