Baylor Professor Thomas Kidd on the revolutionary era

Teaching United States History is lucky to have Thomas S. Kidd, associate professor of history at Baylor University, to discuss the era of the Revolution. Tommy is another amazing scholar, the author of a host of books (including one on evangelicals and Islam from the colonial period to the twenty-first century). Here, he reflects on the revolutionary period, whether we should approach it from the top-down or bottom-up approach, and what documents he likes to use.

1. What drew you to the study of revolutionary America?

My earlier work as a historian was on early to mid-eighteenth century America, especially on Puritanism and the Great Awakening. But as a specialist in religious history, I knew that the topic of religion and the American Revolution was perhaps the most hotly debated historical subject in American popular culture today. So I became interested in writing a religious history of the American Revolution that would be accessible to a broader audience yet still academically rigorous.

2. Major Problems in American History contains essays by Gordon Wood and Gary Nash on the radicalism of the American Revolution. Wood’s piece suggests that radical ideas moved from Enlightenment sages like Thomas Jefferson to the general public and made it possible for women and people of color to push for rights, explores how the push for liberty and freedom came from the marginalized and moved up the social ladder until elites took it on as well. From the perspective of religious and political history, which do you think is more accurate?

I hope it is not a cop-out to say that they are both right! Gordon Wood has brilliantly demonstrated that the Revolution set the stage for future reforms with its expansive notion of equality by creation (“all men are created equal”) and the ideological switch from monarchy to republicanism, and then to democracy. The final transformation into the Jacksonian democracy of white men was not necessarily what the major Founders intended, but their egalitarian justification of independence set loose ideological implications that proved hard to limit only to propertied men. But I think that historians such as Gary Nash correctly note that when viewed from the perspective of African Americans, Native Americans, and women, the short term “blessings of liberty” were limited, at best, and often pressure “from below” was required to advance substantial reforms.

From the perspective of religious history, I do think that the implications of the Revolution were radical, as the Revolution began the process of Americans disestablishing the state churches, fully endorsing religious liberty, and placing American religion on a much more voluntary, entrepreneurial basis.

3. If you had to select only one or two primary documents from the revolutionary period to use in the classroom, which would they be?

|

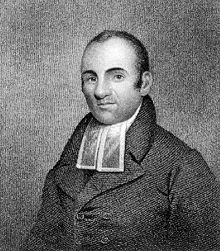

| Reverend Haynes |

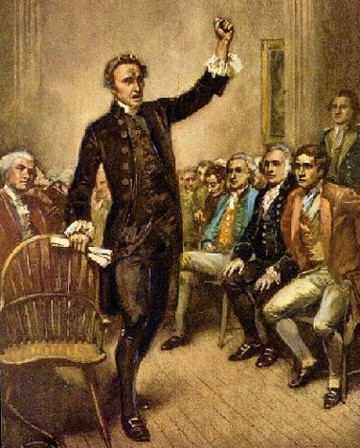

I’m tempted to say Patrick Henry’s “Liberty or Death” speech because I enjoy Henry so much, but I would probably settle on

Lemuel Haynes’sremarkable text “Liberty Further Extended,” in which Haynes, an African American evangelical pastor, employed the Declaration of Independence shortly after July 1776 to make a Christian argument for ending slavery in America. African Americans such as Haynes immediately recognized that if America was to fully embrace the notion that “all men are created equal,” liberty would have to be “further extended” to people of color and slaves.

4. What’s your favorite essay or book on early America?

One could hardly choose a better essay than Perry Miller’s classic

“Errand into the Wilderness.” This not only raises the question of the Puritans’ mission in America, but it also introduces students to a splendid example of historical writing, a topic which receives too little attention among historians.

5. What are you working on now?

I am writing a biography of George Whitefield, the most influential revivalist of the Great Awakening and the most famous person in colonial America. It is due out with Yale University Press in time for Whitefield’s 300th birthday in 2014.