It is the beginning of another academic year and here I am at another new institution with a new student body, new curriculum requirements, and a new conception of the purpose of the history survey. Centre College, my new academic home, has a general education curriculum and the history surveys serve as the gen. ed. class that teaches the research paper. So, in addition to covering the development of the United States to 1865, I need to teach the development of a research paper from idea through execution. It is a tall order that has resulted in me leaving some of my favorite lectures behind in favor of writing workshops and one-on-one meetings.

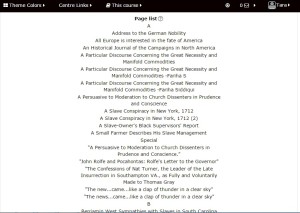

I am hopeful, however, that this process will open up new ways for me to think about teaching the survey. I started the semester with a new project designed to introduce students to reading primary sources but also to working collaboratively. We made a database. This database is a compilation of primary sources that have been assessed, summarized, and analyzed by fellow students and will eventually include over 150 sources. Students located the sources and completed a precis summarizing the text and offering some basic suggestions about the context and purpose of the document.

Students will complete two of these primary source precis and I admit that I rigged the game for the first round by requiring them to find the source in a preselected set of document readers. I wanted them to see what kinds of documents historians marked as important and illustrative of the period. I also wanted to help them learn to evaluate the quality of a source.

And the result is so cool:

Even my students, cynical souls that they can be, remarked on the breadth of material that our first attempt had uncovered. They looked at each other’s work and evaluated themselves based on the work that their peers were producing.

An added bonus is that most of my students chose documents from subjects we will discuss much later in the course. Yet, because I made them identify important events happening around the creation of their primary sources, they are already making connections between their chosen source and our current discussions about the formation of colonial America. For example, our discussion of 18th century religious revivals was strengthened because some students could reference their primary source documents about the Second Great Awakening.

Today was our first “workshop” day where I didn’t try to cover new material but we instead focused on the writing and researching process. I amassed a collection of primary sources and gave them a prompt question (What was the goal of New England colonists in coming to the new world) and their “ticket” out of class was a good thesis statement and three sources that they would use to prove that thesis. This assignment built on their knowledge of primary source analysis but also tried to break down the idea that a thesis statement was really just a vague statement with three points; “colonists came to the new world seeking religious freedom, economic success, and a new social hierarchy.” Most students got out of class early and the students who struggled got more one-on-one attention from me.

So far, both the primary source analysis and the attention to making good arguments fits into my conception of the survey. I’ve always imagined the survey as the place where you learn to answer sophisticated questions. Next week, we delve into secondary sources and topics. I’m less comfortable asking my students to make scholarly arguments and I’m changing my understanding of what the survey class is all about. Writing a research paper means that this class isn’t just about answering sophisticated questions, it’s about creating a sophisticated argument outside the class syllabus.

Do you have a research component to the survey? How do you handle it? Any good strategies?

I teach an American history survey. We don’t have a research requirement, but we are required to introduce primary sources. I have my students write short papers (like an analysis) on primary sources – and I think they learn so much more than reading the textbook.