Let’s start this column with a quiz. Ready? Okay, here we go: Think about a course you teach, and then answer the following question quickly:

Beyond the content of the course, what do you want your students to learn?

If you found yourself drawing a blank, don’t worry: you’re in good company. Whenever I run a course design workshop or individual consultation, I start with that question. The majority of times, I get one of two reactions:

- Silence and a vacant stare; or

- Something along the lines of, What do you mean? The course is the content and the content is the course!

Maybe it’s disingenuous to start with that question, since I know it throws most faculty off balance. Then again, maybe that’s the whole point: to ask something so painfully obvious that the course designer has never even considered it. After all, don’t we often play the same trick on our students?

The good news is that, after only minimal prodding, faculty are usually able to think beyond the confines of course material and identify learning goals transcending their fields. But that doesn’t mean their classes are designed that way, and we have the alarming learning outcomes to prove it (see Richard Arum & Josipa Roksa’s Academically Adrift [2011] on these points). Asked what the “very important” or “essential” goal of an undergraduate education should be, an overwhelming 99% of faculty answered “critical thinking.” With such unanimity, one would expect tremendous improvements in students’ abilities with this skill. Yet, when measured, undergraduates register abysmal critical thinking gains – or even none at all – as they work their way through the college curriculum. Why?

There are myriad contributing factors, but a disconnect between what faculty say their students should learn, and how those faculty actually design and teach their classes, is likely a big factor. Assuming that critical thinking simply happens, no matter what the course design or teaching approach, is both naïve and irresponsible. Further complicating things, there is no universal consensus on what critical thinking is, much less on how it manifests itself in disparate fields.

This being a history teaching forum, I’d like to offer suggestions on the latter issue. The term “critical thinking” in our field has effectively been subsumed by Sam Wineburg’s “historical thinking,” itself a term that appears to mean different things to different people. From a teaching perspective, I’ve largely focused on developing critical/historical thinking in two ways: first, as a willingness to embrace the ambiguity of primary sources, and second, as an ability to evaluate evidence-based arguments about the past. So, if I aim to make my students better critical thinkers, my courses should be designed around primary source analysis and historiography. Just about every other skill in a history curriculum – from research methods to writing proficiency to metacognition to basic content acquisition – can fit under the rubric of, or be marshaled toward, those two key learning goals.

The most important points are these: I have to start the course design process with the desired, field-transcendent goal of critical thinking. I then have to figure out how that skill manifests itself in my discipline. Only after those two steps can I go about designing an effective, learner-centered course. This may sound trivial, but without that procedure, I run the risk of course content dictating my class setup, at which point any likelihood of instilling critical thinking skills has probably evaporated. The fact that measured critical thinking gains in college students are so meager suggests that the aforesaid protocol is too often ignored.

Still looming large is the matter of translating those learning goals into a specific course setup. Yet, it would be a mistake at this juncture to start matching readings and course activities to particular dates in the semester. Before I can do any of that, I have to determine how to assess my targeted learning goals, knowing that some methods will probably work better than others. In addition, I must sequence knowledge acquisition and historical thinking skills development in such a way that students are progressively challenged as the course unfolds. If it sounds like I’m engineering my class in reverse, that’s because I am: this whole process is known as “backward design.”

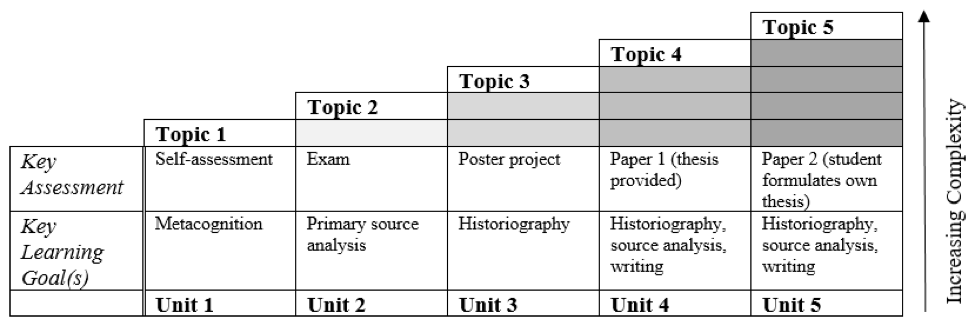

If the points above still seem a bit abstract, let me offer an example from a world history survey course. The assessment of students’ primary source analysis abilities is conducted informally through in-class “think alouds,” and formally through an in-class exam and papers. Historiography assessments are performed via class discussions, poster presentations and papers. Basic course content is not omitted; on the contrary, it remains vital and is primarily assessed in the form of brief quizzes. But content acquisition does not assume a tyrannical centrality: it is interspersed throughout the course as a means to achieve the historical thinking end, rather than being an end unto itself.

The graphic below, which is from an AHA award-winning article I wrote a few years back, lays this all out. One notes a few things in particular. First, learning goals, not content, undergird each unit. Second, key assessments have been identified to measure those learning goals. Third, the course is designed so that it becomes progressively more challenging – not due to sheer volume of material, but because of increasing assignment complexity and cognitive demands. Only after laying this important pedagogical groundwork can I start thinking about specific course themes and readings – the step with which many faculty begin the design process. Although envisioned for a world history course, this framework could work equally well for just about any introductory-level class, even one in U.S. history.

I wrote in a previous column that the teaching barriers between the subfields of history, or even between entirely different disciplines, are largely self-imposed and illusory. As educators, we have far more in common than may appear at first glance, and the role of course design in establishing and achieving learning goals is just one example in my argument. If we begin the design process with our particular fields and course materials in mind, we cut ourselves off from colleagues by assuming our teaching problems are unique. More detrimentally, we run the risk of designing our classes around subfield-specific content, believing that a mastery of material alone will translate into the amorphous “critical thinking” we overwhelmingly identify as crucial for our students.

Now, go back and retake that quiz above. See if you don’t do better the second time through.