*Author note: these are my prepared remarks (with some slight modifications) for a roundtable at the 2019 American Historical Association Annual Meeting in Chicago, Illinois entitled “The American Revolution in World History: A Teaching Roundtable.”

For the last eighteen months I have worked as a social studies teacher in Highlands County, Florida as I researched and wrote my dissertation. Highlands County is among the most rural, impoverished, and conservative counties in the state. I have taught at two places: Highlands Career Institute, which is a high school/vocational school hybrid, and Avon Park High School, which is a traditional high school.

Teaching at these institutions after serving as a graduate teaching assistant at the University of Minnesota has been both a rewarding and an eye-opening experience.

For the confines of this panel, I’ll keep my comments limited to my experiences in teaching the American Revolution, though I would welcome any questions about the general state of high school teaching in Florida during questions or perhaps after the panel.

Florida high school students take United States History 1877-present in the 11th grade. In some cases, this is a fine age for students. Their reading and writing abilities should, at that point, be sufficient to engage in primary source analysis and engage in critical thinking and writing exercises.

However, this is negated by the fact that in Florida, students take the US history to 1877 as either 7th or 8th graders. By the time they sit in front of me as juniors, there is no residual memory of colonial era conflicts, the transatlantic slave trade, religious movements of the early nineteenth century, or other keystone moments in early American history. Students hoping to understand why Colin Kaepernick kneels during the national anthem struggle to place his civil disobedience in context with the struggle for black equality.

And so it is with American Indian history. At the outset of each course I have taught I have asked students to name any Florida Indian tribes. Less than ten percent could name the Seminole Tribe of Florida, despite the fact that the Brighton Seminole Indian Reservation lies in an adjoining county. The state textbook fails students by devoting an entire three paragraphs to pre-Columbian history in North America.

The state is failing its kids in regard to teaching American Indian history.

I have worked hard to mitigate this as best I can and in teaching the American Revolution, I encourage see beyond the confines of colonist versus British narratives. So how do we “blow up” the Revolution? We expand our understandings of it in time and place.

I do this first by beginning my courses on US History since 1877 in pre-Columbian North America and focus on having students identify native communities in Florida such as the Calusas, Timucuas, Apalachees, Tequestas, and so forth. If you are in Georgia or Alabama, Mississippian chiefdoms like Etowah or Moundville would be ideal discussion points. You get the idea.

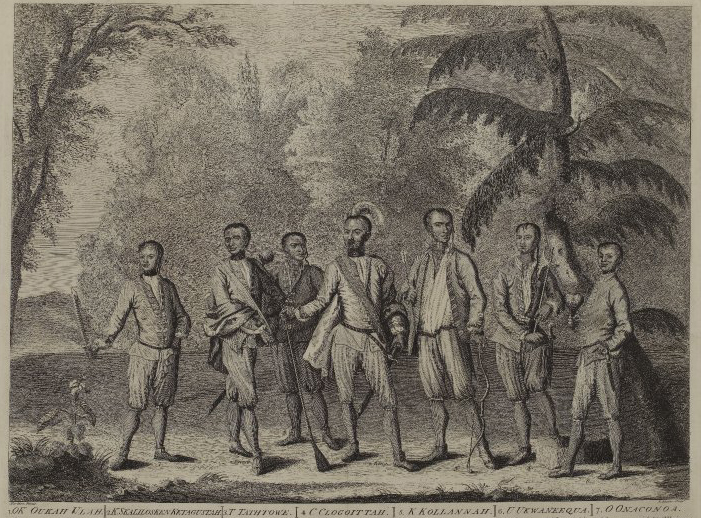

We continue this evolution of a history where Natives are at the center of the discussion by reframing what we conceive of as colonial history. In this case, Michael Witgen provides a better framework by arguing that colonial history “ought to be defined as the history of a particular space or territory organized as a settler colony by the empires of the Atlantic world.”[1] When we do this, we can better incorporate the lives of men like Attakullakulla and women like Coosaponakeesa into discussions of sixteenth through nineteenth century North America. The history, then, breaks away from a white settler epic to the consideration of events and peoples in North America. Hopefully this places Native North Americans on equal narrative footing with whites.

(Attakullakulla, or Little Carpenter, is at the center of this drawing from 1730.)

We can also expand our timelines with which we appreciate the American Revolution. According to Juliana Barr, “If we place the events and processes of European colonialism within the longer timescale of indigenous history, we can better recognize Native strategies for negotiating change and more fully understand the ways that those strategies were the products of Native history rather than simply determined by the environment, socioeconomic variation (for example, horticultural versus hunter-gatherer), or political classification (egalitarian versus chiefdom) at one moment in time.”[2] In sum, we can demonstrate to students that the American Revolution was but one (though important) colonial engagement that Native Americans had to negotiate in order to maintain their sovereignty and guarantee its future security.

Perhaps the best demonstration I have seen of this in action is Kathleen DuVal’s Independence Lost. It not only moves the American Revolution away from New England and centers it on the Gulf South, but it also puts the ambitions of Native men like Chickasaw Paya Mataha and Creek Alexander McGillivray on equal footing with the region’s residents who sought to secure their own independence. It is a stunning piece of scholarship that K-12 educators would not only be wise to read but to incorporate into their classrooms.

Indeed, many historians have worked to answer Colin Calloway’s call in 1995 to better incorporate the history of the American Revolution in Native communities and vice versa. Efforts by Maya Jasanoff, Claudio Saunt, and James Kirby Martin and Joseph Glatthaar are representative of this emerging scholarship.

![Liberty's Exiles: American Loyalists in the Revolutionary World by [Jasanoff, Maya]](https://images-na.ssl-images-amazon.com/images/I/519JUfuX4mL.jpg)

Finally, I would ask that secondary educators ask their students to visit tribal reservations, museums, archives, and perhaps most easily, tribal websites to understand how Native American nations grappled with the American Revolution. Doing so not only helps them understand the conflict from indigenous perspectives, but it helps to reaffirm their presence in modern society and opens a dialogue between the student and Native Americans for the future.

[1] Michael Witgen, “Rethinking Colonial History as Continental History,” The William and Mary Quarterly 69, No. 3 (July 2012): 527-530, quote on 529.

[2] Juliana Barr, “There’s No Such Thing as “Prehistory”: What the Longue Durée of Caddo and Pueblo

History Tells Us about Colonial America,” The William and Mary Quarterly 74, No. 2 (April 2017): 203-240, quote on 205.