“…the social world is always a part of the classroom, that classrooms themselves are social spaces and essentially microcosms of the world outside their wall. All learning, then, happens in a social context because we are learning with and from one another.”

–Joshua R. Eyler, How Humans Learn, p. 66

In the above passage, Eyler expounds on his analysis of schoolteacher Jane Elliott’s 1968 experiment with her third graders. Many might be familiar with her lesson plan; compelled to action after the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s assassination, she grouped her students by those with blue eyes and those with brown eyes. After being treated differently and internalizing their dual experiences of privilege and oppression, Elliott used this opportunity–and the real feelings experienced by her students–to better cultivate empathy toward instances of racial discrimination and violence.

Elliott’s eight year olds had an undoubtedly transformative experience–and I bet they never touched a textbook. In my own classroom, this is something I constantly grapple with: how much do my students need to know in order get the most out of a particular lesson, unit, course, etc.? At the small New England boarding school I teach at, I’m responsible for teaching the highest level of American history offered. While many eleventh grade students will go on to take the Advanced Placement United States History exam, I am not wholly required to prepare them for this exam and have been free to build my own curriculum entirely. And yet, I am drawn by the things I “have to” cover in my course.

But what does it mean to know something? Or to have a strong grasp of “content knowledge”? For the purposes of this blog post, I’m referencing the nitty-gritty details–the dates, the names, the rote memorization–that are all too often equated with the study of history. After years of being told–either explicitly or implicitly through assessments and narrow definitions of success–that these “facts” matter the most, my students are always shocked at the beginning of the year when their study guides filled with definitions do not provide them with the numerical success on exams that they are accustomed to.

Instead, as I ask my students to prepare for an exam or a document-based essay or assignment, I remind them to focus on being “fluent” in the material. In what I’ve come to call “content fluency,” I encourage students to be able to dialogue about the information that they are learning in a variety of mediums–visually, in writing, and verbally. Oftentimes, this includes information about those “key terms” but deemphasizes details in favor of context. In doing so, students are able to more clearly zoom out and identify key patterns and trends in American history, without being weighed down by minutiae. Furthermore, this fluency allows students to more easily and thoughtfully tie their understanding of the past to the present day.

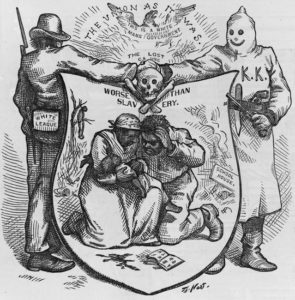

Much of this can be illustrated by my most recent unit on Reconstruction. I start the unit with a famous Thomas Nast political cartoon (“The Union as it was / The Lost Cause, worse than slavery.”, 1874).  Before students read a page of their textbook, they garnered from this cartoon that Reconstruction was filled with violence toward black Americans, despite the revolutionary constitutional changes that took place after the Civil War. Fast forward to today, one week later, when a student asks in passing about a current event, “can’t the government just make a law to change that?” and their peers remind them of the ineffectiveness of Fifteenth Amendment in the face of the KKK, just from what they took from that political cartoon.

Before students read a page of their textbook, they garnered from this cartoon that Reconstruction was filled with violence toward black Americans, despite the revolutionary constitutional changes that took place after the Civil War. Fast forward to today, one week later, when a student asks in passing about a current event, “can’t the government just make a law to change that?” and their peers remind them of the ineffectiveness of Fifteenth Amendment in the face of the KKK, just from what they took from that political cartoon.

Could my students rattle off all of important dates and figures from Reconstruction era? Unlikely. But do they have a firm understanding of difference between social and political change in the 1860s and 1870s, and have they thought about and applied those ideas to the present day? I really think they do. So, as historians and educators, I hope that we continue to push our field from the narrow to the holistic, from the rote to the practical, in the hopes of not just teaching students but teaching humans in all of their social context.