I just wrapped up a week-long trip to Morocco with my senior Global Studies students. After a fall term of exploring what globalization is and a winter term case studying a country–this year, Morocco–the course is predicated on the idea that you can not even begin to grasp the inner workings of a nation-state without setting foot on the ground. Obviously, my students only have a cursory understanding of Morocco at this point–the best I could hope for after only seven days–but their grasp of the content we studied this winter is much richer now that they can root that foundational knowledge in their experiences of the trip.

As United States history teachers, we all seek to do this on some level. The present day is rife with current events to bring into the classroom to reflect the challenges and warnings of our past. That said, for most of us, Washington, D.C. isn’t our backyard, and neither is Ferguson, nor Charlottesville. To our students, even current events in these distant locations mimic the emotional distance of textbook content for them.

I teach eleventh grade American Studies, the highest level of US history at my school, and the expectation is that my students are prepared to take the Advanced Placement US History test at the end of the year. With that in mind, there seems to be little room for experimentation and deviation from the content, but I wanted to work outside these bounds this year, to try my best to ensure that my students truly felt the history they have been learning.

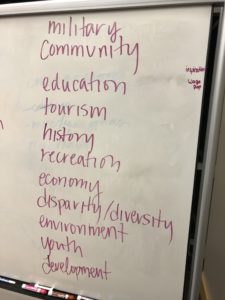

Inspired by youth participatory action research (YPAR) theory and practice, I have been undertaking a project at school this year called Community Connections: Ethnography, History, and Civic Engagement on Aquidneck Island. Through this work, my thirty-four students have conducted dozens of interviews of Newport, RI locals and surrounding community members, have identified common themes and trends, have brainstormed various research questions, and have constructed preliminary annotated bibliographies surveying local and national current events as well as scholarly research.

As I prepare to return from spring break and pick up with the curriculum on the eve of World War I, I’m looking forward to tracing the major events of our national history alongside my students as they work to trace the history of the particular trend or pattern that they have identified. Can they start to unveil why Newport has predominantly white and predominantly black schools, while also learning about the shortcomings of Brown v. Board of Education and the challenges of redlining? Will their knowledge of industrialization and Gilded Age wealth disparities reflect the community divisions of Aquidneck Island?

Attached are some pictures of my students on a night when all thirty-four of them came in for an evening to share out about their interviews and work together to brainstorm themes and overarching questions. In the earliest moments of this project, what I’ve noticed the most is that students have complete ownership of this project. They are invested in this work because–while I’ve provided a frame and some deadlines–they conceived it, they directed it, and they are pursuing it. And, like all historians, they are working toward creating a historical narrative of their own, one that I hope they can contextualize within the broader narrative of American history that we are building together.