A few months ago, at another blog, my friend Eran Zelnik posed a problem related to students’ “emotional well being” in history courses. At the end of a semester teaching early U.S. history, he wrote,

there was something hanging in the air after class that still felt too depressing for a group of 18 year-old freshmen. It was, oddly enough, when I went back to my own work on my book, that I finally realized what was troubling me. It was the narrative trajectories I keep employing [as a lecturer]. Virtually all of them start on a positive note and end on a somber one.

From lectures about New England and Virginia during the late seventeenth century, through lectures on the American Revolution, to lectures on Redemption and Jim Crow, they all started with opportunities lost and ended with the retrenchment of power structures of one variety or another to the detriment of the majority.

Since—as I keep saying—narrative is fundamental to history at all levels, I think Eran is right to raise this as an issue.

The problem crystallized in my mind one day a few years ago. In the modern U.S. survey, I was covering 1950s consumer society and mass culture. My young students seemed entranced by the cultural optimism I was describing. I commented on their reactions, and some of them explained that they were fascinated by—and perhaps needed (I’m pretty sure that was their word)—a vision of American optimism about the future. For they had come of age in a pessimistic time. And, I suspect, they had been paying attention to the narrative trajectory of some of my other lectures.

(Don’t worry. I did plenty of things to complicate their picture of 1950s optimism.)

This matters for reasons beyond emotional health. First, historians’ habits of pessimism tend to produce cynicism about public affairs. Second, if left unchecked, our pessimism actually does an injustice to the vulnerable and marginalized people of the past—people who built lives of meaning for themselves amid the large-scale public failures we describe.

In fact, this can result in major analytic failures on the part of historical educators. To take one example: I’ve had college students express surprise after learning that a substantial population of free African Americans (amounting to nearly half a million people by 1860) existed from the colonial era onward. It was a concept that had never occurred to these students—ever. Our dominant narratives about slavery, in structure if not in substance, tend to submerge that population’s history completely, at least in high school.

Similarly, I’ve had students express shock upon learning that a central fact of enslavement was the separation of families at auction. This fact, of course, does not exactly lend itself to historical optimism—except that it tells us that enslaved people were, in fact, forming families, and often fighting to hold them together.

That is not a minor point. That is a reality that could express a human being’s entire world.

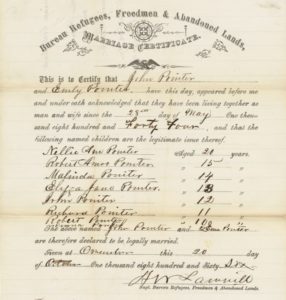

So when I talk about Reconstruction, I like to show my students a specific primary source: a marriage certificate for John and Emily Pointer of Kentucky, who attested their relationship in front of a Freedmen’s Bureau official in October 1866.

As I point out to my students (or rather, invite them to point out to me), this document is unusual for a marriage certificate. It says not that the Pointers had just married, but that they had been married for more than twenty-two years. The certificate recognizes not only their bond with each other, but also their bond with eight surviving children.

As I point out to my students (or rather, invite them to point out to me), this document is unusual for a marriage certificate. It says not that the Pointers had just married, but that they had been married for more than twenty-two years. The certificate recognizes not only their bond with each other, but also their bond with eight surviving children.

For twenty-two years, I tell my students, Emily and John Pointer somehow had held their family together in the face of overwhelming injustice. Now, for the first time, the law recognized what they had built.

I don’t show my students this image in order to tell them a story about the arc of history bending toward justice, or the transcendent ideals of the Declaration of Independence unfolding themselves gradually across time, or any such convenient thing about American public life.

I show them this document because it provides us a glimpse of people making a life—making their own form of freedom before the majesty of the United States deigned to recognize it.

Telling stories like that—as many as we can—is my solution to the problem.