This is not a new or particularly original question but it has been on my mind since I started teaching my own course: how do you get a classroom of young, college freshmen to relate to a small group of elite men dead for well over two hundred years? How do you teach a classroom that is an image of multiculturalism – a true New York City composite of black, Latino, Asian and white students from a full spectrum of ethnic, gender, religious and immigrant experiences – to find a realistic connection with that past, a past that figures so prominently in our political present? Many of my students were not raised on the fables of George Washington’s honesty or Benjamin Franklin’s genius: some did not attend high school in the United States and are hearing of the “founding fathers” largely for the first time. Yet no matter their background, each and every person in my classroom had an opinion when I showed them an unusual scene from a 2009 poetry night at the White House.[1]

The spoken word song, featuring a biographical introduction to the highly unusual life of Alexander Hamilton, is now one of dozens in Hamilton, a new musical at the Public Theater written by Lin Manuel Miranda. Given the shows box office success and undeniable originality, it’s not surprising that there has been considerable commentary, particularly when it involves a cast as diverse as my classroom.[2] Generally the reviews have been raves, with the music – a fusion of hip-hop, rap battles and classic ballads – blending almost seamlessly with an astute interpretation of the politics of mobility, the power of authorship and the nature of legacy. To cap it off, Hamilton is staged as a quintessential story of a New York Icarus, which New Yorkers (if you’ve ever met one) cannot get enough of.

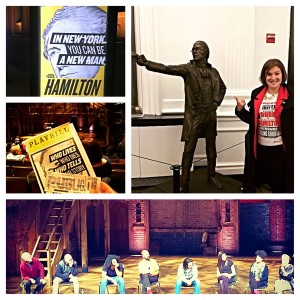

With all that said, this post might seem a bit late to the party. As Exhibit A below indicates, clearly I am a fan of the show, so I will restrain myself from a bulleted list of all the features that I liked and simply state that I already have my tickets for July 13th, the first night of Hamilton on Broadway.  With so many different facets of the production discussed already, from comparisons to a 1917 play with very different dynamics to the reactions of politicians today in the audience, I would like to focus on three specific elements: poetry, pedagogy, and production slogans.[3]

With so many different facets of the production discussed already, from comparisons to a 1917 play with very different dynamics to the reactions of politicians today in the audience, I would like to focus on three specific elements: poetry, pedagogy, and production slogans.[3]

It is fitting that Miranda’s first performance at the White House was a scene that described the significance of a poem, “On the Hurricane of 1772,” in Hamilton’s exit path from St. Croix. It was his skills as a creative writer, often overlooked in light of his economic and legal expertise that triggered Hamilton immigrant experience, an observation that my students noticed right away. “He was a poet?” a usually quiet man with a slight accent asked me. “He was certainly a writer,” I replied, adding, “I am not sure that clear genre boundaries that we think about today would have mattered to him as much.” “But he was that poor?” a more talkative women followed up, “that is amazing.” Poetry, my students noted, is no longer the widely popular enterprise of the early national and antebellum periods – almost always, it is a second career, not the one in which a writer can support themselves. But Miranda is also a poet, albeit of a more modern variety.

Now, I have assigned readings for homework from The Federalist and we talked about the Constitution and politics in the 1790s for nearly three lectures. My class this semester is very solid: they do their work, they participate and they think critically. But I have not gotten a reaction, before or since, like their incredulous, amazed faces, after watching Miranda’s abridged performance. This could be a reaction to the expression of a historical figure’s life in honest, blunt terms and in a medium that resonates more deeply with their current popular tastes. Unfortunately though, despite a last name that often makes people think otherwise, I am not a musician in any sense of the word, so I cannot rewrite the remainder of my lectures this semester to a lyrical backdrop.[4] Nor, quite frankly, do I think that I should. There is merit in a classroom environment where a professor and students can sit and discuss the material in an intensive, direct conversational setting.

But as we move across the first half of the survey course, it becomes easier and easier to whittle down American history into slogans. No taxation without representation! The Revolution of 1800! The Missouri Compromise! Manifest Destiny! More often than not, these slogans not only lack poetry, they lack merit altogether. But Hamilton’s production lines are quite a bit more nuanced. “In New York You Can Be A New Man” and “Who Lives, Who Dies, Who Tells Your Story” encapsulate not only the dilemmas of one brilliant yet flawed outsider’s experience but – forgive the dramatic phrasing, this is about a drama after all – the nature of history itself. Our profession has its own production slogans that emphasize the importance of evolving pedagogy, of creating a classroom environment where the realities of history must be taught along side the skills for individual interpretation. Immigration is one of the most contested issues in current American politics and its equally divisive history cannot be ignored, especially when it connects so profoundly to the lives of my students. Hamilton is an interpretation, much like my lectures, but its style resonates. To be clear, I am not saying, “let’s just make stuff up so our students like class more” but rather that there is a poetic, exciting way of presenting fact, which the best lecturers and Miranda undoubtedly already know. History-as-story, even one where a small group of privileged white males dominated the corridors of power, is far more complicated by the broader culture of economic, racial, ethnic, religious, sexual and gender politics. That might seem obvious to professionally trained historians but to college freshmen, that narrative is not as clear. The #HamiltonPublic playbook might present some strategies for changing that.

When Hamilton moves to Broadway, it will have a new production slogan, “an American musical.” Fittingly, the question of how history evolves, of how it is understood by generation after generation, is in many respects an American story, albeit one that often lacks a musical backdrop. This might be a simplistic conclusion but I think, like so many basic principles, it can be overlooked. If the question is how to make this history matter beyond the academy, then as a teacher, I need to consistently work on knowing my audience, on finding better – or more poetic – slogans.

—

[1] You can watch the performance here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WNFf7nMIGnE

[2] For example, The New York Times, The New Yorker, The Wall Street Journal and the early America-focused blog The Junto have discussed the production.

[3] Here are two pieces on these subjects, respectively: http://www.playbill.com/news/article/exclusive-compare-hamilton-2015-with-hamilton-1917-first-publication-of-lin-manuel-mirandas-lyrics-343516 and http://www.nytimes.com/2015/03/28/theater/hamilton-puts-politics-onstage-and-politicians-in-attendance.html?_r=0

[4] Several times a year I am asked by musical friends/acquaintances/strangers I just met if I am related to the infinitely gifted composer, conductor and theorist, Nicolas Slonimsky. I am related to him but regrettably have inherited none of his talents outside of avid audience member, to the horror of my high school violin and chello teacher.