I have very mixed thoughts about college football, but as much as I am a fan of any team, I root for the Missouri Tigers. And no, not because of the events of the past week. My “fandom” began in 2007 when Chase Daniel (who is one of the, if not thee, most underrated back-up quarterback in the NFL) led the Tigers in an incredible Heisman-nominating season. Call me a front-runner if you will but my interest was and remains piqued, especially in the wake of Michael Sam’s historical actions. But why I bring up Daniel specifically has as much to do with where he currently works as where he went to college: tomorrow, the Tigers are set to play at Arrowhead Stadium, the home of the Kansas City Chiefs. Daniel, along with wide receiver Jeremy Maclin, both Mizzou alums who play for the Chiefs, have not (as of now) commented on the events underway at their alma mater. They are of course under no obligation to do so: while they once occupied the paradoxical status of “student-athlete,” they are two of the rare few that transitioned into the professional, or paid, category.

For those who haven’t been following, here is a brief recap: following a string of bigoted incidents on the Columbia campus, escalating in recent weeks – you can find timelines here and here – Jonathan Butler, a graduate student in the education program, began a hunger strike that ended with the removal of university President Tim Wolfe from office. With the support of their coach, Gary Pinkel, the Tigers football team joined the protest by refusing to play in this Saturday’s game. There’s been grumbling about the actual unity of the team on this decision, with an anonymous player noting the that if the team was winning more games, they would not have joined the strike. But ultimately, football did tip the scales. On Monday, Wolfe resigned, saving the university over a million dollars in violated contract fees should the Tigers have refused to play. Further resignations and suspensions followed in the wake of threats of violence on campus but the Tigers will still take the field.

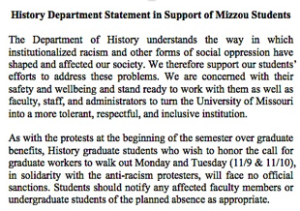

There are a myriad of issues here: most glaringly, racism in higher education, methods of protest, student and professorial accountability, the place of money in college. But what is especially striking (pun completely intended) to me about the Tiger’s actions is how clearly it complicates the very construct of a “student-athlete.” I’ve written about this subject before, more though how it relates to unions, intellectual property and image rights. In the case of Mizzou football, it becomes apparent how much leverage players can have in certain situations, and how absolutely little they have in others. Take for example this statement below, found on twitter, from the Missouri history department: With a reference to an earlier protest over the increasingly strained position of graduate students (their healthcare benefits are completely under attack) the work of historians and football players in-training are brought into the same conversation. Student-athletes, like graduate students, are a contradiction in many respects. Both are “paid,” although not with a salary: we receive stipends to cover essential bills and work for the school (either in the classroom or in the stadium). Our compensation is a degree. There are pros and cons to this structure but my point, in no way an original one, is that its a grey area. There are thousands of institutions of higher eduction in this country, of which only a minuscule percentage have elite (and by elite I mean high revenue generating) athletic programs. Of that community, fewer still are public. In the public (and thus accountable to a greater degree of regulation) community of university’s with elite athletic programs, even less have the type of football teams that capture the national attention, i.e., media coverage and television contracts. For more precise statistics, you can check out this site.

With a reference to an earlier protest over the increasingly strained position of graduate students (their healthcare benefits are completely under attack) the work of historians and football players in-training are brought into the same conversation. Student-athletes, like graduate students, are a contradiction in many respects. Both are “paid,” although not with a salary: we receive stipends to cover essential bills and work for the school (either in the classroom or in the stadium). Our compensation is a degree. There are pros and cons to this structure but my point, in no way an original one, is that its a grey area. There are thousands of institutions of higher eduction in this country, of which only a minuscule percentage have elite (and by elite I mean high revenue generating) athletic programs. Of that community, fewer still are public. In the public (and thus accountable to a greater degree of regulation) community of university’s with elite athletic programs, even less have the type of football teams that capture the national attention, i.e., media coverage and television contracts. For more precise statistics, you can check out this site.

There are only a small pool of student-athletes who are capable of generating the capital and accessing the public platforms to pull off what the Tigers have done. Us history doctoral students have neither, and the majority of student-athletes in the United States are far closer to us than they are to the Tigers. But we each occupy this ambiguous educational space and now have an example of a powerful link between our two professional slash student realities. The Tigers have been very brave in taking a position on these issues: whether or not you agree with their stance is your prerogative. For anyone in the labor no-mans land that student-athletes find themselves in at these types of institutions, with so much riding on their performance, it is a bold risk, especially for students of color. It goes so far beyond not proverbially “biting the hand that feeds you.” Sure, if their season was more productive, they might not have done it. But can you blame them?

I’ve spoken with a few friends and colleagues about this over the last few days and have heard several provocative comments that I’m still mulling over, so consider this wrap-up very much a thought-in-process. Professional athletes, who have the contract, who are getting paid (although there is certainly plenty of room for debate on how organizations like the NFL treat their players as well…) are told to focus on the game above all else. So are graduate students, although the playbook looks a bit different. Often if a professional athlete speaks out on an issue and you agree with their opinion, they are a hero exercising their free speech. If you don’t agree with them, then suddenly they have no business articulating any opinions and should stick with “what they’re good at.” But the whole point of an education is to teach you how to think for yourself! A student-athlete, no more than a PhD student, is not being “ungrateful” for expressing opinions: that’s what they are ostensibly in college to do. They are laboring on that field, in the gym, in front of the camera, to earn the right to go to class. That’s what they are getting PAID to do. So, while there is a lot to be discussed, debated, developed and hopefully improved in the dynamic between athletics and education, the Tigers football players are not denying their roles as student-atheltes, they are owning them.

.