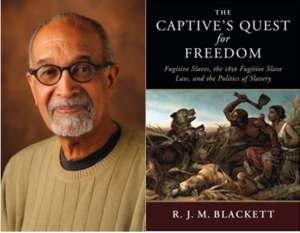

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Richard Blackett, Andrew Jackson Professor of History at Vanderbilt University, the author of The Captive’s Quest for Freedom: Fugitive Slaves, the 1850 Fugitive Slave Law, and the Politics of Slavery (Cambridge University Press, 2018).

A major feature of the Compromise of 1850, which hoped to resolve existing political and territorial issues following the war with Mexico, the Fugitive Slave Law (FSL) was the most politically consequential law of the antebellum period, some might even say of the entire 19th century. Among its many draconian features was the denial of habeas corpus and trial by jury, pillars of western jurisprudence. Anyone who refused the demands of local and federal authorities to aid in the recapture of suspected fugitives were liable to hefty fines, in effect turning citizens into slave catchers. Hearings were to be adjudicated by commissioners, quasi-judicial officers, whose decisions were final. For every decision to return a suspect, commissioners were paid $10 but $5 if the decision went against the claimant. The cost of rendition were to be borne, exclusively, by the federal treasury. The law, in effect, nationalized slavery. In doing so, it generated widespread opposition and gave impetus to an increasingly radical abolitionist movement. Scores of meetings, in cities, small towns and villages throughout the north, vowed to resist its enforcement. These meetings gave voice to a vibrant and organized inter-racial opposition at whose center were members of black communities who stood most to suffer from the law communities that, over the years, had welcomed and sustained unspecified numbers of former slaves. A critical feature of the resistance was the formation of vigilance committees pledged to aid fugitives and resist enforcement of the law. Their membership, made up almost exclusively of blacks, was supported by a coterie of white lawyers whose services were provided pro bono. All but one of the Acting Committee of Philadelphia’s Vigilance Committee, for example, was African American. They conducted the daily business of the Committee temporarily housing escapees, shepherding them through the city, and sending them safely on to other stations on the Underground Railroad. Its white lawyers, members of one of the state’s two abolitionist societies, were always on hand to defend suspected fugitives. The black community never failed to turn out at hearings to voice their opposition to the law and express their support for the accused. When the opportunity presented itself, organized groups of blacks stormed hearing rooms and spirited away the accused to safety. As a last resort, when it appeared the accused would be returned, opponents offered to purchase the accused.

A major feature of the Compromise of 1850, which hoped to resolve existing political and territorial issues following the war with Mexico, the Fugitive Slave Law (FSL) was the most politically consequential law of the antebellum period, some might even say of the entire 19th century. Among its many draconian features was the denial of habeas corpus and trial by jury, pillars of western jurisprudence. Anyone who refused the demands of local and federal authorities to aid in the recapture of suspected fugitives were liable to hefty fines, in effect turning citizens into slave catchers. Hearings were to be adjudicated by commissioners, quasi-judicial officers, whose decisions were final. For every decision to return a suspect, commissioners were paid $10 but $5 if the decision went against the claimant. The cost of rendition were to be borne, exclusively, by the federal treasury. The law, in effect, nationalized slavery. In doing so, it generated widespread opposition and gave impetus to an increasingly radical abolitionist movement. Scores of meetings, in cities, small towns and villages throughout the north, vowed to resist its enforcement. These meetings gave voice to a vibrant and organized inter-racial opposition at whose center were members of black communities who stood most to suffer from the law communities that, over the years, had welcomed and sustained unspecified numbers of former slaves. A critical feature of the resistance was the formation of vigilance committees pledged to aid fugitives and resist enforcement of the law. Their membership, made up almost exclusively of blacks, was supported by a coterie of white lawyers whose services were provided pro bono. All but one of the Acting Committee of Philadelphia’s Vigilance Committee, for example, was African American. They conducted the daily business of the Committee temporarily housing escapees, shepherding them through the city, and sending them safely on to other stations on the Underground Railroad. Its white lawyers, members of one of the state’s two abolitionist societies, were always on hand to defend suspected fugitives. The black community never failed to turn out at hearings to voice their opposition to the law and express their support for the accused. When the opportunity presented itself, organized groups of blacks stormed hearing rooms and spirited away the accused to safety. As a last resort, when it appeared the accused would be returned, opponents offered to purchase the accused.

Such a law was necessary, its proponent insisted, because of a troubling recent rise in the number of escapes. There were some spectacular escapes which only lent urgency to the call for a more stringent law, one with teeth, as proponent were fond of arguing. Abolitionists and black community organizations had made it next to impossible to enforce the existing fugitive slave law passed in 1793. In addition, some northern states had adopted what they called Personal Liberty Laws that made renditions increasingly difficult. It is next to impossible to determine with any certainty the numbers who fled in the decade before the law’s adoption. In some areas, however, the pattern was clear. In the northern counties of Kentucky, especially those bordering the Ohio River, for instance, the flow of escapes was so constant that local slaveholders organized defensive societies to protect their interests. They registered their slaves with the organization, offered substantial rewards for the recapture of runaways and hired slave catcher locally and as far away as Lake Erie in an effort to stem the flow of escapes. They also relied on local courts and a bewildering assortment of state laws and local ordinances to punish those involved in helping slaves to escape. There were slaves who aided other slaves to escape but for reasons we cannot always fathom, chose to remain. Free blacks, the bane of the system, it was assumed were at the center of a ring of subversion. More troubling still were black and white northerners who, as slaveholders put it, came south to entice the enslaved to escape. In spite of their best efforts, local slaveholder organizations could not stem the tide of escapes.

The Captive’s Quest for Freedom attempts to understand this complex set of political issues in the critical decade before the start of the Civil War. It is the first attempt to understand the wide-ranging impact of the law and the reactions it produced. It posits that by their actions, the enslaved entered and influenced the debate over the future of slavery. Their actions provide us with a unique opportunity to understand what they thought about freedom and what they did to subvert the system of slavery. Their determination to be free also affected the abolitionist movement forcing its proponent to take a different some would say a more active, approach to the undermining of a system they abhorred. The book suggests we take a new look at the politics of slavery in what is undoubtedly a historically pivotal decade, one which pays special attention to the actions of the enslaved. It calls for a new examination of the political consequences of escapes, their impact locally, as well as what occurred when attempts were made to reclaim escapees in a free state. The more dramatic escapes pushed state and federal proponents of the law to ask questions about the nature and future of the political compact. The FSL, in the eyes of many, was the last best chance of holding the Union together. On the eve of the Civil War, the actions of the enslaved, the failure of the law to stem the flow of escapes, opposition to and resistance to its enforcement in many areas of the North, all combined, in the eyes of secessionists, to justify their decision to quit the Union. The fact that in the vast majority of cases fugitive slave hearings before commissioners resulted in renditions seemed to matter little to proponent of secession. Too many had escaped, the cost of recapture was prohibitive and, more galling of all, slaveholders and their agents had been roughed up and, in one instance, killed trying to reclaim their property. The final irony is that, in leaving, slaveholders found their property more vulnerable than ever.