You know the scene. It’s Alec Baldwin’s only scene. In just over seven minutes, Alec Baldwin’s “Blake” harangues four hapless real estate salesmen to Always Be Closing. The film, of course, is Glengarry Glen Ross, and its language should probably be kept out of your classroom. But there is an essential message to Baldwin’s diatribe: Go and Do Your Job. Do what you were called to do.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the roles of historians. I continue to debate how much activism comes with the job. But one thing I am certain about is that historians cannot leave the job in the classroom or the office. Too much depends upon it.

We seem, now, to live in a new Jacksonian era characterized by a revival of willful ignorance. Historians, continually frustrated by this turn of events, must be ever vigilant to spread our knowledge in new and engaging ways.

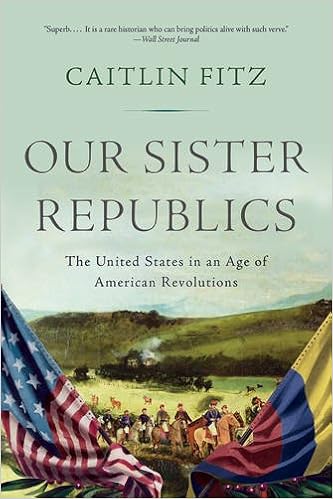

Despite Gordon Wood’s pronouncements, scholars are doing just that. Renowned scholars like Joanne B. Freeman and Kathleen DuVal have turned increasingly towards trade presses in an effort to appeal to larger audiences and have succeeded. A roundtable at the 2018 annual meeting of the Society for Historians of the Early American Republic seemed to be in agreement that any stigma within academia regarding trade presses for first manuscripts was quickly evaporating. This certainly appears to be true when considering Caitlin Fitz’s recent tour de force, Our Sister Republics.

Podcasts have also made tremendous headway, perhaps none more so than Liz Covart’s Ben Franklin’s World. With over 200 episodes already released, Ben Franklin’s World is easily among the favorites of early American historians. The Age of Jackson Podcast, by Stanford graduate student Daniel Gullotta, is another example of how scholars are reaching audiences far beyond the classroom or even the manuscript. I recently assigned an episode of Ben Franklin’s World to high school juniors and will be writing up the results shortly. I have also considered adding a podcast to my tiny YouTube collection, though my plate remains incredibly full at the moment.

I suspect that if you’re reading this you’re aware of the power of social media, where historians and teachers are increasingly providing perspectives on modern events or historical analysis and trends. Twitter has proven to be the preferred platform, with some historians attracting tens of thousands of followers. Others, like Kevin Kruse, has amassed over 100,000 followers via his observations and feuds with Dinesh D’Souza (these have not been pretty for D’Souza). Kruse’s superb usage of 280-character tweets have allowed him to inform far more people than could ever fit in a Princeton classroom. More so, twitter has acted as a medium through which followers can be casually introduced to a scholar or teacher and then investigate their works more fully via books or other media.

While I have nowhere near the followers of Kruse, Heather Richardson, Kevin Gannon, or Honor Sachs, it has proven to be an effective way for me as a junior scholar to promote my work and interests. This website’s founder, Ben Wright, approached me after Historians At The Movies began to gather attention (I’ll be devoting an entire post to #HATM soon). I’m writing a dissertation and will be going on the market within the next two years. I’m hoping the additional exposure I develop from this platform will translate into interviews and job offers.

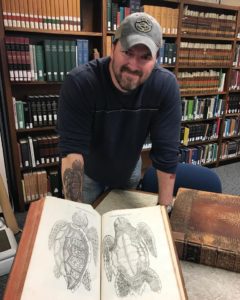

I even use the tattoos on my arms to discuss the Atlantic World. My left arm features the skeleton from Blackbeard’s flag. My students love this. I speak to the fact the Edward Teach made his name in a short amount of time and yet we remember it hundreds of years later (yes, I’m drawing on the romanticism of pirate mythology, but I’ll do whatever I can to inspire my young people). On my right is a large recreation of a sea turtle by Ulyssis Aldrovandi. I get remarks on this every single day. When people compliment the artwork I ask if they like turtles. Of course the answer is yes–who doesn’t like turtles? (Shame on you if you don’t.) But I speak to the fact that the image is from 1645 during the era of Conquest and exploration and how naturalists were part New World empire construction. I ask if people have heard of Atlantic history (most haven’t) and I tell about I study the interplay of continents and empires from the 16th through 19th centuries. I try to have a couple books floating around in my head for recommendations, but beyond that, I make sure that people have a positive interaction with a historian. Maybe one day they’ll be part of a conversation about funding for schools or universities and remember the little thing I taught them or the pleasant experience we had. Maybe they will encourage their children to study history. Maybe they’ll just have a good day and smile. All of these are enough.

All of these scholars and teachers are engaging the public outside the classroom in exciting ways that challenge myths of academics in ivory towers. I suspect YouTube is also a growing medium for historians, though I have to see its potential mined like other platforms. My challenge to you, dear Americanist, is not to leave your gifts in the classroom. For us, there can be no off switch. Our times demand that our talents and expertise be available to far more people than those who grace our doors.