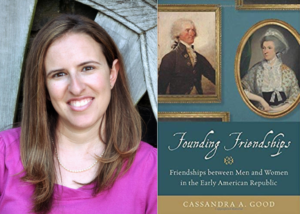

Founding Friendships argues that friendships between elite men and women in the early American republic were more than possible—they were commonplace. These relationships exemplified key republican values of the era: choice, equality, freedom, and virtue. Men and women found affection, emotional and practical support, and political benefits from these friendships.

Founding Friendships argues that friendships between elite men and women in the early American republic were more than possible—they were commonplace. These relationships exemplified key republican values of the era: choice, equality, freedom, and virtue. Men and women found affection, emotional and practical support, and political benefits from these friendships.

The book begins with an opening chapter suggesting the contours and lived reality of these friendships through three pairs of friends: Abigail Adams and Thomas Jefferson; William Ellery Channing and Eloise Payne; and Charles Loring and Mary Pierce. These pairs are unusual in that both sides of their correspondence survives, and there is a lot of it!

The second chapter looks at popular discourses on friendships between men and women through conduct manuals, magazines, poetry, and novels. I argue that this literature offered conflicting messages about the value and risks of such friendships, limiting people’s ability to imagine and describe their relationships. The following chapter then demonstrates how this contributed to confusion about the line between friendship and romance in friendships between men and women.

Public perceptions about mixed-sex friendships were important: a friendship misinterpreted as a romance could ruin a woman’s reputation. Thus chapters four, five, and six focus on how men and women positioned their relationships within their communities to ensure that their friendships appeared safe and chaste. Chapter four looks at general strategies, while chapter five examines letter writing and chapter six uses material culture to look at the rules of safe and proper gift exchange.

The final chapter concludes with an examination of how these friendships could offer political access, information, and influence. It builds on the historiography of women’s political role in this era to show how power operated through relationships. In many ways, this chapter is the key historiographical contribution.

Founding Friendships demonstrates that historians should think more broadly about gender roles, emotions, and what constitutes politics. I believe firmly that defining politics merely as voting, elected officials, and legislation misses a great deal of the fundamental operations of power and governance. Particularly in the early republic, personal relationships were key sites for shaping politics, and those relationships often included women.

The book also shows relationships where the traditional gender roles don’t apply—women as the more intellectual ones in a pair, or the ones with the political influence; men as sources of emotional support and vulnerability. These friendships were the most egalitarian relationships available between a man and a woman, despite the rise of companionate marriage. The cultural fixation on marriage as the pinnacle of emotional fulfillment both then and now has obscured the fact that people gained support and affection from an array of relationships.

While the book largely confines theory to the footnotes, it’s also deeply engaged with the new historiography on emotions. I treat emotions as historically contingent and argue that we cannot assume that our contemporary understanding of the language of feelings matched that of the past. I hope readers will come away thinking more deeply about their assumptions about emotional expressions in the past.

Founding Friendships can be helpful for teaching the US history survey as well as upper-level courses in Early American Republic; Nineteenth Century US; or US Women’s/Gender/Sexuality. In the survey, I hope that faculty can integrate a more nuanced approach to teaching about gender roles and the ideology of separate spheres, as well as emphasizing a more capacious definition of politics. At under 200 pages of body text, the book could work well for a week in an upper-level class to address gender and politics in the Early Republic. For a single class session, the final chapter on politics could work well. Faculty teaching classes on gender or sexuality would find chapter three, on the line between romance and friendship, useful. Reviewers have especially lauded the chapter on material culture and gift exchange, which could be useful in a number of classes, including a methodology course.

Indeed, the wide range of sources I used in the book can be helpful for discussing with students how historians read evidence. My approach to literature and portraiture is surely different than that of literature or art history professors. It might also be useful for students to consider how to find sources on something that the historical literature says doesn’t exist and that isn’t noted in library or archive catalogues. That’s something I’d be happy to Skype into classes to talk about, because it certainly required some creative thinking! One example: the friendship albums I write about in the material culture chapter are often catalogued as commonplace books or autograph albums, when they’re not really either.

One fun opportunity for integrating this book into the classroom would be to have students read some of the letters that were exchanged between Thomas Jefferson, George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, John Adams, and their female friends. Fans of the Hamilton musical would be especially interested in the correspondence between Hamilton’s sister-in-law Angelica Schuyler Church and Jefferson. Most of the letters I cite are available as published transcriptions via Founders Online, and many of Jefferson’s and Washington’s letters are also available as digital scans from the Library of Congress. I give students a chance to try transcribing original documents and then share the published versions. Students could also look at a set of correspondence between friends and identify the different rules and rituals the friend pairs are following (Mandy Cooper designed this activity for her course and it worked well).

Undergraduates often start from the assumptions that women were totally confined to the household in early America and that it’s impossible now—and in the past—for men and women to be friends. The politics chapter probably does the best job of showing the first isn’t true. On the latter, it can be a tougher sell. I usually start with the fact that emotions themselves are historically conditioned and give the example of the ideology of romantic love not emerging until the late 18th century. That shocks most students, and it lays the groundwork for saying that we’re looking at the past as a foreign country where we can’t take emotional expressions at face value. It’s a good opportunity to challenge preconceptions and encourage historical thinking.