“Dance is a cry and a celebration.” -Savion Glover

I often experiment with how to merge cognition with affect in the classroom. I wrestle with if or how there might be ways to bring students into history through emotion. It is an experience I think many historians have had in archival or on site visits where a place or object affects us beyond its fascination and historicity to, for lack of a better word, a kind of soul level. But many students have not had this privilege which perhaps explains why history can seem so boring and impersonal to them. Having an interest in psychology and the philosophy of mind, I decided to invite students to see if they could have an aesthetic experience on the theme of slavery and emancipation through watching the legendary Savion Glover in a tap dance improvisation that he did as a part of a series of performances in New York City in 2013 marking the 150th anniversary of emancipation called “The Rhythm of Freedom: Emancipation 150.”

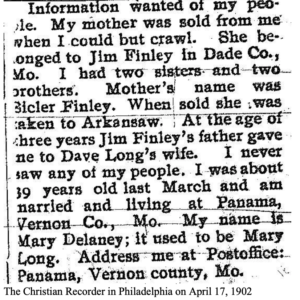

In a previous class we had read an array of newspaper ads by formerly enslaved people seeking to reconnect with relatives after emancipation (such as the one here). Reading ads by adults and even elderly people seeking information about siblings or parents they had been separated from during childhood or infancy is certainly heart wrenching, and students had expressed that. So I decided that we needed to consider not just the pain and brutality people experienced, but also to consider how people survived such unimaginable circumstances, and why someone might have had the impulse and hope to take out such an ad. Implicitly and explicitly, I am often making an argument to students as to why “culture” matters, and how things like music and dance are not extra window dressing professors toss in to add to the “real” historical study of presidents and wars, but that culture carries equal historical heft and import. Cultural practices can be a means of survival, a way to maintain and strengthen one’s ties to others and to one’s own humanity. When we study painful events of the past, it is worth asking how and why did people keep going? What inspired them and kept their souls intact and strengthened their bonds with each other or their creator? What can we learn about them through these practices, and can we even learn something about ourselves in the process of this inquiry?

Reading ads by adults and even elderly people seeking information about siblings or parents they had been separated from during childhood or infancy is certainly heart wrenching, and students had expressed that. So I decided that we needed to consider not just the pain and brutality people experienced, but also to consider how people survived such unimaginable circumstances, and why someone might have had the impulse and hope to take out such an ad. Implicitly and explicitly, I am often making an argument to students as to why “culture” matters, and how things like music and dance are not extra window dressing professors toss in to add to the “real” historical study of presidents and wars, but that culture carries equal historical heft and import. Cultural practices can be a means of survival, a way to maintain and strengthen one’s ties to others and to one’s own humanity. When we study painful events of the past, it is worth asking how and why did people keep going? What inspired them and kept their souls intact and strengthened their bonds with each other or their creator? What can we learn about them through these practices, and can we even learn something about ourselves in the process of this inquiry?

Before showing the video, I went over a bit of the history of tap dance, its emergence from African dance styles, its first well-known African-American artist William Henry Lane aka “Master Juba” and the potential local influences on it in New York City’s Five Points neighborhood from Irish step dancing. I also raised the issue some students might have forgotten from the previous semester or not known that drumming, a practice that dates back perhaps 8000 years, was outlawed in many American enslaved communities preventing them from maintaining a sacred cultural tradition. “There is one instrument older than the drum, however,” I tossed out to my students. “What is it?” Some students guessed various instruments, while another confidently asserted “the voice” which is mostly what I was looking for, but I expanded it to include “the human body.” Even in the absence of drums, many rhythms and sounds can be made with our hands, feet, and voices, and dancing styles may have evolved uniquely in response to the painful void created through the outlawing of drums.

I then introduced students to the concept of an “aesthetic experience” as it is viewed in the field of philosophy, which is:

- an experience qualitatively different from everyday experience, an exceptional state of mind

- fascination with an aesthetic object that elicits high arousal and attention

- a strong feeling of unity with an aesthetic artifact

An aesthetic experience can also be transcendent, which some psychologists describe as an experience in which one’s sense of self fades away leading to a feeling of connection to something broader (nature, humanity, one’s creator, etc.).

I asked students if they could relate to having had an “aesthetic experience” in the past, even if they hadn’t called it that, such as listening to a song and feeling a deep sense of connection or viewing some natural landscape and feeling transported beyond oneself in an inexplicable way. In response I saw an agglomeration of heads nodding almost imperceptibly, perhaps more as involuntary bodily remembrances of such experiences rather than in response to my inquiry.

So the class experiment was, can we watch the video performance, keeping in mind the larger history we had discussed about slavery, emancipation, and the history of tap dance and see if we could have an aesthetic or transcendent experience? Could we consider how Savion Glover might be using his body both as a musical/artistic instrument and as a surrogate for someone more than a century before him who wrestled with how and whether to keep going despite the agony of unspeakable indignities such as family separation, brutality, and injustice? Can we follow his movements in the performance and look for potential embodiments of sorrow and joy, frustration and hope? Can we see or even feel how Savion Glover describes dance as both a cry and a celebration? And through that, can we consider how tap dance in the nineteenth century might not only have been an expression of emotional states, but also as an actual method of survival, a tool for deciding to live another day amidst an ocean of uncertainty, a physical embodiment of anger and grief, as well as hope and joy under the weight of many sorrows? Instead of solely thinking historically, could we feel the history? And could we do so through focusing intently on the aesthetic performance itself? With tap dance absent an external music source, the body essentially creates the music through the rhythmic steps that the body simultaneously dances to. It is a beautiful circuitry, and one that mirrors self-determination and self-sufficiency, that one can dance to the sounds originating from the dance itself.

Perhaps you can watch the video as well with an eye towards having an aesthetic experience (in the philosophical sense). Notice any physiological or affective changes in your own body in reaction to Glover’s emotive performance. And if you feel some changes or experience transcendence or an aesthetic experience, can it be considered historical pedagogy? Can emotional transcendence actually teach history?