Most survey textbooks and courses focus on LGBTQ history only a few times at most and usually only in the latter half of the twentieth century. For some time, Stonewall has been included in U.S. history textbooks and courses. Other topics commonly covered in more recent years are the AIDS crisis and the Lavender Scare during the Cold War. These are improvements from the total lack of representation of the fairly recent historiographical past, but relegating the topic only to the post-war era is problematic (like maybe they didn’t really exist before 1950?) and also implicitly suggests that LGBTQ people only make it into history class when they have been persecuted, died in large numbers, or accomplished an uprising (which was in reaction to systematic persecution). Don’t get me wrong, these are crucial, multi-dimensional events worth covering, but I am arguing here that LGBTQ history needs coverage in multiple time periods and should include aspects of everyday life as well.

Adding more of anything to the already hectic schedule of a survey course may be the last thing you want to consider. It necessarily means skipping over some material from your current lectures or textbook. And giving short shrift to trust-busting or the Great Awakening may feel like historical sacrilege, but hear me out. Your students’ lives will not be changed by George Whitefield, but some of them might be changed by hearing about two virtually unknown women named Charity and Sylvia. Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake shared a home and life as a married couple in everything but law in Early America. They moved in to a rented room together in Weybridge, Vermont in 1807 and celebrated the anniversary of their moving-in day thereafter. They had a silhouette portrait created of themselves and hung it in their home (above image). They co-owned a successful tailoring business. Throughout some of their lives, especially their earlier years, they experienced vicious rumors or ostracism from family or community members because of their same-sex intimacy and their not having married men. But for a significant portion of their lives they were pillars of the community, active members of the church, Sunday school teachers, founders of a benevolent society and a part of each other’s families. Charity wrote a poem to Sylvia including the line: “May we pass our whole life, and our minds be united in one.” A description of their relationship by their nephew, the poet William Cullen Bryant, is one I ask students to parse:

Charity Bryant and Sylvia Drake shared a home and life as a married couple in everything but law in Early America. They moved in to a rented room together in Weybridge, Vermont in 1807 and celebrated the anniversary of their moving-in day thereafter. They had a silhouette portrait created of themselves and hung it in their home (above image). They co-owned a successful tailoring business. Throughout some of their lives, especially their earlier years, they experienced vicious rumors or ostracism from family or community members because of their same-sex intimacy and their not having married men. But for a significant portion of their lives they were pillars of the community, active members of the church, Sunday school teachers, founders of a benevolent society and a part of each other’s families. Charity wrote a poem to Sylvia including the line: “May we pass our whole life, and our minds be united in one.” A description of their relationship by their nephew, the poet William Cullen Bryant, is one I ask students to parse:

If I were permitted to draw aside the veil of private life, I would briefly give you the singular, and to me most interesting history of two maiden ladies who dwell in this valley. I would tell you how, in their youthful days, they took each other as companions for life, and how this union, no less sacred to them than the tie of marriage, has subsisted, in uninterrupted harmony, for forty years, during which they have shared each other’s occupations and pleasures and works of charity while in health, and watched over each other tenderly in sickness; for sickness has made long and frequent visits to their dwelling. I could tell you how they slept on the same pillow and had a common purse, and adopted each other’s relations, and how one of them, more enterprising and spirited in her temper than the other, might be said to represent the male head of the family, and took upon herself their transactions with the world without, until at length her health failed, and she was tended by her gentle companion, as a fond wife attends her invalid husband. I would tell you of their dwelling, encircled with roses, which now in the days of their broken health, bloom wild without their tendance, and I would speak of the friendly attentions which their neighbors, people of kind hearts and simple manners, seem to take pleasure in bestowing upon them, but I have already said more than I fear they will forgive me for, if this should ever meet their eyes, and I must leave the subject.

The story of their lives is fairly simple and unremarkable in some ways, similar perhaps to other “unremarkable” but enriching histories such as that of Martha Ballard, but sharing it with students accomplishes several important things that can bring historical and personal relevance to students as well as perhaps alter their perception of the field of history. For LGBTQ students and allies, the story of Sylvia and Charity offers an example of a same sex relationship from the past that is notable for its very lack of exceptionality by its relative acceptance within its community. It surprises many students that any such relationships existed in the open or even at all in this time period. Their story also shows students that historians study and interrogate the lives of everyday people, not just presidents and wars, something that many students describe as reasons for not relating to history. And lastly, the story of Sylvia and Charity is a moving example of the quiet resistance of two people living their true selves. (All info here based on the 2014 book by Rachel Hope Cleves, Charity & Sylvia: A Same-Sex Marriage in Early America, Oxford University Press).

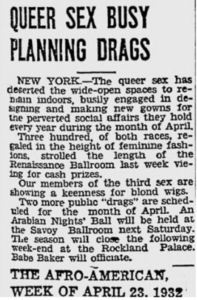

The early 20th century and prohibition are particularly rich for showing students a visible public celebration of LGBTQ social life. Images and newspaper coverage of drag balls that attracted thousands in New York and other major cities expand a notion of the time period that many students already have of a heteronormative though slightly rebellious era of flappers, jazz, speakeasies, and bootlegging. Instead of expounding on those aspects of the period that many students already know, instead discuss and show the drag balls, the “pansy craze”, same sex couples dancing in popular nightclubs, and mainstream newspapers touting the popularity—almost trendiness—of LGBTQ culture (see George Chauncey, Gay New York: Gender, Urban Culture, and the Making of the Gay Male World, 1890-1940). When you talk about jazz, use an image or song of one of the many lesbian artists of the period like Gladys Bentley or Lucille Bogan’s “B.D. [bull dagger] Woman’s Blues.”

Hate crimes and violence against LGBTQ people (especially trans women of color) are alarmingly high at this moment. Visibility in history matters. I am arguing that you can contribute to that visibility when you literally put images on screen during your lecture and include LGBTQ history throughout your course. Don’t underestimate the power of feeling seen and included for the LGBTQ students in your class, many of whom are facing enormous challenges and threats to their safety in their everyday lives. Also demonstrating to all students that same sex sexuality and various gender expressions have existed throughout time can move the dial toward attitudes of broader inclusivity. Despite the legalization of same sex marriage and mainstream acceptance of many LGBTQ celebrities, data shows that acceptance of LGBTQ people has actually declined in recent years.

There is a problem with LGBTQ history only being covered through relatively recent events, specifically Stonewall or the AIDS crisis (while, to be clear, I am in total support of covering those crucial topics too); it delimits LGBTQ visibility solely to crisis or (a false sense of) triumph. Last semester after discussing the 1920s-30s drag balls, one student came up to me after class, and seemingly breathless with excitement, exclaimed, “Why have I never known about this?!!” The resonance he felt was palpable. Not many subjects garner such reactions. So go ahead, throw out a few topics in your present survey class to make room for more LGBTQ history. You may not see the impact, but there will be one.

~