In every class, I choose to teach a few new texts that I have never read. Sometimes this will include one texts. Other times it will include more. For this semester, in my multicultural American literature course, I chose two new texts that I had never read before: Hala Alyan’s Salt Houses and Omar ibn Said’s 1831 narrative. I plan to write about each of these texts, but today I want to focus on Said’s narrative. I had students read Ala Alryyes’ introduction to A Muslim American Slave: The Life of Omar Ibn Said and his translation of Said’s text. Alryyes’ introduction provides useful information to situate students in the period, specifically focusing on David Walker’s Appeal and the American Colonization Society.

Said’s narrative is not long; in fact, it’s less than 15 in Alryyes’ edition. As well, Said’s text does not follow the tropes that James Olney and others have identified with the slave narrative tradition. It does not begin with, “I was born.” There is no scene of family separation. There is no scene of violence. There is not quest for literacy. There is no, apart from one early instance, any escape. None of the characteristics appear.

Omar ibn Said

Said’s narrative, on the surface, reads like a pro-slavery text written by an enslaved man. However, as Alryyes’ argues, and I do as well, this is far from the truth. To show this, we must remember that someone asked Said to write his narrative. Said tells us that Sheikh Hunter asked him, but Alryyes could not determine Sheikh Hunter’s identity. Alyrres does note that the narrative found its way to ACS member Timothy Dwight and that it appeared in 1831, the same year as Nat Turner’s Rebellion.

Alyrres’ asks, “As terror swept the South in the wake of ‘the Turner Cataclysm,’ were Southern Colonizationists and sympathetic slave owners looking for a ‘good’ slave narrative to counter the effects of Turner’s dangerous example?” This is a question worth considering, and it is a question to keep in mind when reading Said’s narrative. Unlike individuals like Frederick Douglass, Harriett Jacobs, Henry Bibb, and more, Said remained enslaved. Would it behoove him to speak openly about the horrors of slavery? No, it would not.

How then, are we to read Said’s narrative. Alryyes points out that we need to read it as a subversive text, one that confronts those who enslave Said and others. Of of the only instances where Said directly confronts the institution of slavery occurs near the end of the narrative when he writes, “I reside in our country here because of great harm.” Apart from this, not much appears, at least on the surface, to confront the peculiar institution. Rather, Said uses his rhetoric, specifically passages from the Quran, to speak against his enslavement.

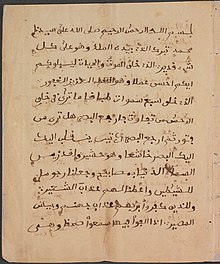

Said opens the narrative with a passage from the Surat al-Mulk, and in his 1925 translation, J. Franklin Jameson deemed this section “not autobiographical.” He wrote, “The earlier pages of the manuscript are occupied with quotations from the Koran which Omar remembered, and these might be omitted as not autobiographical . . . but it has been thought best to print the whole.” What constitutes “autobiographical”? When one writes an autobiography, one constructs the text, in whatever way one chooses, presenting information and omitting information. By beginning his narrative with the passage, Said is partaking in the construction of his own narrative, and the passage serves as an undercurrent throughout.

The main section of the sura that reverberates over the short narrative are the verses that discuss those who suffer in hell for not accepting the prophet Muhammad’s message.

When they are flung into its flames, they shall hear it roaring and seething, as though bursting with rage. And every time a multitude is thrown therein, its keepers will say to them: “Did no one come to warn you?” “Yes,” they will reply, “he did come, but we rejected him (as a liar) and said: ‘God has revealed nothing: you are in grave error.'” And they will say: “If only we had listened and understood, we should not now be among the heirs of the Fire.”

Alyrres asks us to consider who is the person who came to warn those suffering in hell. As he writes, “On the surface, it is Muhammad who brought Islam as the warning to the Kuffar, the infidels who denied him. . . . [I]n the hidden meaning, Omar ibn Said is the one who brought the message, suffered for it, and was denied.” From the very beginning, Said positions himself as a messenger of the wrongs enacted upon him and as a messenger to those who hold him in bondage.

When Said begins to speak about his experiences, he writes, “We sailed in the big Sea for a month and a half until we came to a place called Charleston. And in a Christian language, they sold me. A weak, small, evil man called Johnson, an infidel (Kafir) who did not fear Allah at all, bought me.” Two things stand out in this passage. First, as he does throughout the narrative, Said refers to the enslavers’ language not as English but as “a Christian language.” This initial move sets up their language in contrast to his own.

The second aspect makes us think back to the sura that Said begins with. Johnson, the man who bought Said, “did not fear Allah at all.” Here, we need to think about those in hell who say that no one warned them about the punishment. Johnson’s lack of fear does not necessarily point to a lack of knowledge or lack of someone warning him, but it does point to a direct rejection of Allah’s message.

Later, Said invokes his audience by writing, “O, people of America; O, people of North Carolina: do you have, do you have, do you have such a good generation that fears Allah so much?” This invocation comes after he describes his owner, John Owens. He talks about the Owens family in a positive manner. In this context, Said’s question about “a good generation” could refer to them; however, that is not the case.

Immediately after this, Said states, “I am Omar, and I love to read the book, the Great Qur’an,” and he mentions that the Owens “used to read the Bible” to themselves and to him. In the same paragraph, he writes, “Allah is our Lord, our Creator, and our Owner and the restorer of our condition.” Here, Said makes it explicitly clear that the question he asks earlier should serve as a warning to his audience.

Instead of being a pro-slavery narrative to ease the fears of the community after Nat Turner’s Rebellion, Said subverts the text, presenting himself as the messenger who has come to warn his enslavers of their impending doom. Did white readers understand this? I do not know, but I tend to agree with Alyrres that between the two moments I mention above “Omar’s language is rich in hidden meanings, with nuances that separate him from the white community of his owners, to guard his identity even as a slave.”

The nuances are his way of resistance. They are a way to maintain his identity amidst the horrors of slavery. They are a means to communicate with others who could see past the surface into the depths of the text, pulling from the sura and applying it to the rest of the narrative. They, as Alyrres points out, “permit him to reconstruct a community that is not the one circumscribed by slavery.”