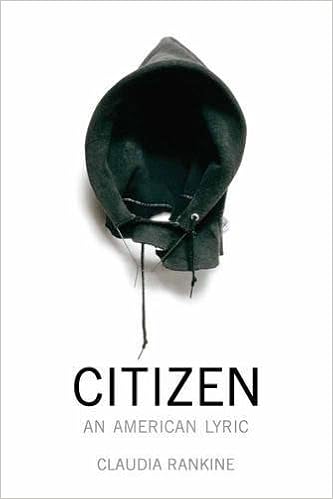

In Citizen: An American Lyric, Claudia Rankine uses the term “historical selves” in one of the vignettes in section one. There, the speaker, addressing the reader, talks about you and a friend. The friend

argues that Americans battle between the “his-

torical self” and the self self.”

This battle causes tensions between you and the friend, even though you have a lot in common, because the weight of history bears down on both you, in all its ugliness. When this occurs, the speaker says, “sometimes your historical selves, her white self and your black self, or your white self and her black self, arrive with the full force of your American positioning.”

The “historical self” exists within us, whether we wish to acknowledge it or not. It sits there, inside our psyche, rooting around in our skulls, pulling us away from truly intimate connections and denying us access to our “self self,” a position devoid of all of these lingering specters.

When one of you says something, sparked possibly by the “historical self,” “your attachment seems fragile, tenuous, subject to any transgression of your historical self.” That moment severs the shared connection, the mutual aspects that connect you and your friend.

Rankine has spoken about the intimacy within the encounters in Citizen. Speaking to Aaron Coleman, she said,

I had a friend say to me—he’s a white man and he was party to one of the interactions in the book—he said to me, “I think what you’re doing is pushing people away so that they can get closer.” And I love that phraseology partly because—though I don’t experience it as pushing anyone away—I experience it just as responding to what is being said to me, responding to what is happening—even as he might experience me pushing him away—but I think ultimately, for him, it was me showing up, fully, and saying, “this is not acceptable to me. And if you want to be my friend maybe don’t do this again.” You know, that kind of thing. So I think the book is about showing the breaches inside that intimacy, but those breaches wouldn’t exist if we didn’t presume intimacy.

Intimacy appears again and again in Citizen, and Rankine highlights the ways that the “historical self” breaches that intimacy, lacerating the connection.

She continues by stating, ” We are social animals. We want connection. We want . . . understanding. We want intimacy. But if the terms of that intimacy feel dishonest, or feel only possible with the acceptance of your erasure, then that’s painful.”Intimacy allows for these conversations, it allows for us to work through our “historical selves” in a path towards our “self selves.” However, we cannot allow that intimacy to erase anyone. We cannot allow it to erect barriers, keeping us separated from one another.

The building of walls, barricades, enclosures, or whatever we want to call them, harms everyone. People propose these structures, basing their rhetoric on fear that if we don’t have them then we will be in danger from people and forces from the outside. This logic only works to separate the mind, cleave it in two, from one side that says “Love thy neighbor” to the other that says “I don’t want you here because you’re not like me.” How can we reconcile these two sides? We can’t, and that is what Smith points out in Killers of the Dream.

Writing about her childhood, she states, “Something was wrong with a world that tells you love is good and people are important and then forces you to deny love and to humiliate people.” This unsustainable severing of logic and myth “shuts ourselves away from many good, creative, honest, deeply human things in life.” It denies us the opportunity to truly form intimate relationships, learning from and loving one another.

She continues, “I began to understand slowly at first but more clearly as the years passed, that the warped distorted frame we have put around every Negro child from birth is around every white child as well.” These frames cause the child, and adults, to become “stunted and warped,” contorting and twisting themselves into steel-like frame that gnarls and bends, unable to rise straight into the air. This contorting, trying to meld the myriad contradictions brought about by the “historical self” that Rankine references, erects barriers between individuals.

Another vignette in section one of Citizen focuses on friends eating at a restaurant. After you and your friend order salads, your friend tells you about her son who did not get into the college he and she wanted him to go to, the college where you, her father, her grandfather, and others attended, “because of affirmative action or minority something.” Your friend does not remember the politically correct term for the current moment, but she asks, “weren’t they supposed to get rid of it?”

Once you ask where her son ended up, she tells you that he got in to a “prestigious school,” but this fact does not “assuage her irritation.” This moment, this breach of intimacy between the two of you, this appearance of the “historical self” that privileges whiteness, wealth, and a history of oppression, breaches the intimacy between you and your friend, and “[t]he exchange, in effect, ends your lunch.” The final line reads, “The salads arrive.”

The walls, barriers, and the “historical self” stunt and warp our minds. When we teach these things to our children, in a myriad of ways, we hinder them from experiencing true intimacy with other individuals. We separate them ” from many good, creative, honest, deeply human things in life.” By doing this, we perpetuate the “historical self” both in the psyche of the oppressed and the oppressor. The continued presence of the “historical self,” in its myriad forms, cleaves us in two.