If you are teaching the second half of the U.S. survey this semester, you are probably about to cover the 1940s and 1950s. Do you plan to include the history of children and youth as you teach these decades? If not, here are a few ideas to get you started.

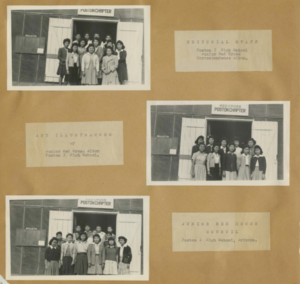

First, there are various sources available online that can help you incorporate the experience and perspective of young Japanese and Japanese Americans during World War Two. A particularly rich source is the scrapbook “Out of the Desert” (see Images One and Two).

Images One and Two: Students at Colorado River War Relocation Center, Poston, Arizona, compiled by Ray C. Franchi and Paul Takeda, Out of the Desert Scrapbook, Marguerite Archer Collection of Historic Children’s Materials, Special Collections, J. Paul Leonard Library, San Francisco State University, http://digital-collections.library.sfsu.edu/digital/collection/p16737coll3/id/394.

Created in 1943 as part of the Junior Red Cross correspondence program, the scrapbook includes artwork and descriptions about living at Poston, as well as moving essays in which the school-aged youth reflect on their place in American society. You might pair the scrapbook with these oral histories that are available on Children & Youth in History. Referencing Valerie Matsumoto’s City Girls: The Nisei Social World in Los Angeles, 1920-1950 would help you contextualize these sources and speak more fully to the experience of Japanese and Japanese Americans before, during, and after the war.

You could also incorporate the history of the “teenager” during the war using Seventeen magazine. When it was published in 1944, Seventeen was one of the first publications to solely target a teenage girl audience, and the magazine captures the growing economic, social, and cultural significance of this age group in the 1940s.[1] In fact, it was not until the early 1940s that the term “teenager” was really adopted to denote a demographic distinguishable by a shared culture and traits, such as high school attendance, participation in leisure activities, and a degree of economic independence. The historical developments that gave rise to the “teenager” likely dovetail with topics you already plan to address as you cover World War Two. For example, wartime economic growth led to young people’s increased spending money. While some youth filled labor shortages as part-time employees after school, other youth enjoyed increased allowances as their parents’ incomes rose. Of course, wartime shortages and rations limited civilian consumerism, but this did not stop merchandisers and advertisers from targeting young people as a potentially lucrative demographic.[2] In order to avoid being labeled as unpatriotic, Seventeen, for example, featured articles such as “What Are You Doing About the War?” and advertisements for clothing like the “Winged Victory Jumper” (see Image Three).[3] Using Seventeen not only allows you to include the history of children and youth during World War Two, but also foreshadow the importance of gender and consumerism in post-war culture. After all, it was the white, middle-class teenage culture captured in Seventeen that informed mainstream images of youth culture after the war.

Image Three: “Winged Victory Jumper,” Seventeen, September 1944, 56.

As you move to the decade following the war, why not use the courtship practice of “going steady” to illustrate the emphasis on the nuclear family in American society? By 1950, “going steady” had replaced the form of courtship common since the 1920s. While the old system—termed “rating and dating”—emphasized competition and valued the number of dates young people went on, the new system of “going steady” celebrated marriage and the security of just one partner.[4] Couples who were going steady abided by a variety of teenage cultural norms that included the exchange of tokens, such as letter sweaters and class rings, and going on dates.[5] This dating convention thus reflected concerns about security during and after the war, as well as postwar culture’s emphasis on the nuclear family and consumerism. If you usually use a clip from Leave it to Beaver to illustrate post-war culture, consider using a clip from the episode “Wally Goes Steady.”

Of course, you will simultaneously be working to shatter the myth of an idyllic, Leave it to Beaver-esque 1950s. To do this, I highly recommend having your students listen to the podcast Bandstand and the Closet by Sexing History. The podcast tells the story of how Bandstand erased both blackness and queerness from the image of youth culture. I assigned the podcast just as I would any other reading and began our discussion with a video clip of the show. I found—and my students’ feedback confirmed—that the podcast was an engaging and accessible way to teach the intersection of race, sexuality, and popular culture in the early Cold War.

While I am sure that you are already making difficult decisions about the material you have time to cover in your course, I hope that you will include the history of children and youth. As these resources suggest, their history is crucial to the 1940s and 1950s and likely intersects with what you already plan to cover.

[1] Kelly Schrum, “‘Teena Means Business’: Teenage Girls’ Culture and Seventeen Magazine, 1944-1950,” in Sherrie A. Inness, ed., Delinquents and Debutantes: Twentieth-Century American Girls’ Cultures (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 138. Also see Schrum’s Some Wore Bobby Sox: The Emergence of Teenage Girls’ Culture, 1920-1945 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004).

[2] Schrum, “‘Teena Means Business,’” 136.

[3] “What Are You Doing About the War?” Seventeen, September 1944, 54, 56, 84. Seventeen is available through the database “Women’s Magazine Archive.” See also Schrum, “‘Teena Means Business,’” 136.

[4] Beth Bailey, “From Front Porch to Back Seat: A History of the Date,” Magazine of History 18, no. 4 (July 2004): 24, https://ushist2112honors.files.wordpress.com/2010/08/bailey-courtship.pdf.

[5] Bailey, “From Front Porch to Back Seat,” 25.

Amazing article! I’m totally implementing your research into the classroom.

Thank you,

NjB

I’m so glad this post is helpful!