When I was in graduate school, I TAed for a class on the Civil War. The prof usefully told us that the class would have almost nothing to do with the battles or the military strategy of the war or the generals, and everything to do with the context, the politics, and the ramifications.

A small handful of students immediately left and are now probably serving as re-enactors somewhere in western Pennsylvania or northern Virginia.

The midterm question for the course, though, has always fascinated me: By what year was the civil war inevitable?

My heart-of-hearts answer has always been 1793, with the invention of the cotton gin. What makes the cotton gin so transformative, of course, is that it’s central to the democratization of slavery, if such a phrase makes any sense at all. But with a few acres of land, a handful of slaves, and access to a cotton gin, a small farmer could make his or her way. Thus slavery expands westward, and regional variations become a looming crisis, which quickly becomes inevitable.

Right now I’m teaching slavery and religion (particularly the religion of the slaveholders–slave religion is next week), and I’m using the churches to show how slavery goes from being a “necessary evil” to a “positive good” in the 1820s and 1830s, decades that I’ve just taught them were the time of the Second Great Awakening, perfectionism, Finneyite revival, and the creation of a Benevolent Empire. Now this?

Religion was only one of the three arenas of the South’s justification of slavery–economics (Dew) and politics (Calhoun) were the other two. But religion is so useful because the major denominations divide in the 1840s, prefiguring the national divide a short while later. Plus, trying to explain the Curse of Ham is incredibly difficult, because it just makes so little sense at all.

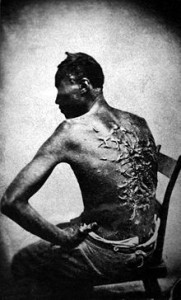

This leads us to a discussion of willful ignorance. Clearly willful ignorance was at the heart of the “positive good” argument, and this contrasts sharply to the image of slavery many students have inherited from Gone With The Wind. And that’s part of the point. Teaching them that willful ignorance leads in sometime horrific places and to images that nevertheless shape our world goes a long way toward teaching them about the variables in history, and that the past isn’t even past.

On the other hand, teaching them that willful ignorance is not just a thing that is located in history is another problem all together.