Continuing our series on the ways we bring research into the classroom, Christy Pottroff discusses how and why she uses physical letters as a pedagogical tool. Christy is a a Mellon Dissertation Fellow in Early Material Texts at the McNeil Center for Early American Studies and a Ph.D. candidate in English at Fordham University. Her dissertation, “Citizen Technologies: The U.S. Post Office and the Transformation of Early American Literature,” examines the surprising extent to which the U.S. Post Office Department influenced early American literature. Christy is also at work on two digital humanities projects, Going Postal and the National Burial Database of Enslaved Americans.

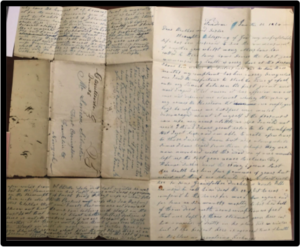

Nothing validates an eBay impulse-buy like watching students learn something meaningful from the new goods. With about $30-worth of well-timed bids, I put together a small batch of nineteenth century letters for classroom use:

The letters themselves are pretty mundane. One is a receipt for flour, another requests mail forwarding, one is an Ohio court summons, and the rest are personal letters between friends. While these aren’t the kinds of letters that drive historians to the archive, for many students, they are revelatory. The experience of squinting and laboring over nineteenth century handwriting is unfamiliar and rewarding for most undergraduates. They are often surprised by how big and soft the paper is. And though they know what letters look like (yes, even millennials get snail mail), these old letters have different stamps, markings, and envelopes than any twenty-first century postal patron is used to.

I bring these nineteenth-century letters into the classroom because they have the power to defamiliarize students’ understanding of a familiar form. Students have likely read older letters reprinted in textbooks and other secondary sources. But a handwritten letter–folded up around itself, addressed, and sealed with wax–holds its own power. These objects are intimately, immediately, and undeniably human. By putting these letters into the hands of students, I hope not only to connect students to a more human past, but also to build close-reading skills I expect students to apply more broadly in my courses.

From this small collection, my students’ favorite letter–without fail–was penned in 1834 by Delia in Garrettsville, Ohio. She begins “Through the blessings of God my unprofitable life has been preserved to see the commencement of another year.” Delia then lists a series of ailments that arose from “the misfortune [of sticking] the tine of a fork into [her] thumb.” The letter continues in the same cheerless tone–to the delight of some students and the frustration of others. Delia, arguably (and flippantly) the nineteenth-century Debbie Downer, helps connect twenty-first century students to the lived experience of Ohio frontier life in 1834.

But sore-thumbed Delia isn’t alone in the letter. On the third page, students encounter writing in another hand. Betsy, Delia’s neighbor and the letter’s second writer, addresses her “absent friends” and describes local goings on. Like Delia, Betsy offers an intimate and very human perspective on Ohio frontier life. She writes about a mutual acquaintance who “has made out rather poorly…She is so feeble and nervous that she is almost afraid of her shadow.” Taken together, Delia and Betsy have led students to some incisive observations about religious language, medical knowledge, community-building, and isolation in the nineteenth century.

And yet, this letter has value beyond its intended messages. When students encounter Delia and Betsy’s letter as a material object, they can see the places where the handwriting gets tight. They can see that there is virtually no empty space on the page. If these women had so much to say to their distant friends, why didn’t they write two separate letters?

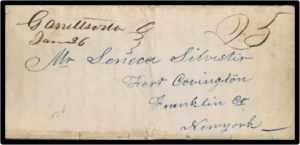

As a scholar of the early American postal system, this is a question I love. To answer it, I direct my students to the letter’s address label (found in the middle of the letter’s fourth page) and ask them to make sense of what is there. Drawing on their familiarity with today’s postal system, this is usually quick work. The letter is addressed to Mr. Seneca Silvester in Fort Covington, New York. And they can see that the letter left Garrettsville on January 26th. What is somewhat less familiar is the looping “25” in the top right corner.

Here, I get to showcase my own research specialty. Before the advent of postage stamps (in 1847), postage was handwritten by a postmaster. And a letter’s cost was determined by the number of sheets of paper and the distance it travelled. Accordingly, Betsy and Delia wrote their letter together on a single sheet of paper to save money. Sending a letter through the U.S. postal system at 25 cents a pop was no small cost (about $7 today)–and this postage rate kept many Americans from regular correspondence until the rates were drastically lowered in the 1850s. By this same logic, the reason we encounter so many letters from government officials and soldiers is that these men were granted the franking privilege, which eliminated the high cost of postage completely.

More than simply offering a glimpse into the lives of two women from the past, Delia and Betsy’s letter directs students toward questions about the state of communications in the nineteenth century. These questions rise to the surface when students encounter the letter as a material object. While letters in secondary sources often omit address labels and translate text into more readable forms, original letters are peppered with stamps, postmarks, and seals that speak to the postal systems that delivered them. By decoding these postal hieroglyphics, students can determine how far a letter travelled, what it cost, and how long it took to get there. Attention to these seemingly mundane details have a great deal to tell us about about communication, proximity, and distance in the early United States.

For students, close scrutiny of postal hieroglyphics feels like historical detective work. They are decoding a historical artifact in a way it isn’t usually understood (I mean, it’s no National Treasure, but it’s still pretty fun). By putting old letters in their hands and giving them a postal vector of analysis, I encourage students to come to new insights about individual letters and the state of early national communication more broadly. In doing so, these letters and their postal systems provide an excellent and very concrete lesson in building historically-minded arguments. This experience encourages students to read closely and think critically about a given text, and to connect their analysis to a larger idea about the postal system.

These lessons about communications systems are especially important in today’s digital world. We rarely give a passing thought to the physical and digital infrastructure that enables our communication. Indeed the very language of the internet–the cloud, cyberspace, the web–obscures its physical and very human origins. In turn, this metaphorical language shapes the way we understand (or don’t understand) how our own communications systems work. By looking to our nineteenth-century communications forebears and asking questions about their network’s infrastructure, accessibility, cost, and privacy, we can encourage our students to start asking better questions about our own.