The sensory and emotive associations of place hold the most immediate connection for people when they think of a familiar landscape setting. In teaching spatial theory, music about place can be an excellent pedagogical tool that instructors can use to engage students in thinking about the way space is constructed in the songwriter’s mind. This process of imagining place through song helps students expand the opportunity to explore critical geography which then helps students to deepen their understanding of United States History.

Critically examining geography means analyzing the interrelationships of space, place and identity. The forces of economic, social and cultural practices work on the inhabitants of a place as well as work to form the place itself. As such, critical approaches in geography invites an analysis of history where the relationships between the space and the individual connects student understanding of how both operate in the foundation of place identity.[1]

Henri Lefebvre, one of the foremost philosophers of space and author of The Production of Space, distinguished what he referred to as perceived space, a space which embodies the interrelations between institutional practices and the individual’s daily experiences and routines. In short, the ways people mediate the spaces they inhabit with the realities of the social, economic, and political machinery that constructs the place itself.[2]

For instructors, this marriage of spatial theory with lyrical descriptions of place offers a framework for helping students develop their thinking about constructions of place and how it relates to critical geography. The result will deepen their understanding of the past.

Let us begin with a place that many have visited and where multitudes live: New York City. There are many songs written about New York. We’ll start with a verse from “New York State of Mind”, not by Billy Joel but by hip hop’s great, Nasir Jones:

I never sleep, cause sleep is the cousin of death

I lay puzzled as I backtrack to earlier times

Nothing’s equivalent to the New York state of mind…

This track is from his first album Illmatic(1993) and the song captures the realities of life in New York in the 1990’s for a young person who has the talent to make it big as a performer, but is affected by the circumstances of the street life. This life is comprised of living in overcrowded dwellings with the hardworking, the fast talking, and the felonious amidst constant police presence. The song mentions the crimes that take place in such locales and we imagine a part of New York that is extremely far away from fifth avenue glitterati- a much more punitive landscape within the Big Apple. Nas describes the New York he knows and thus formed the conception of his New York- a New York where Queensbridge projects figures prominently in the center. As instructors we can distill a life narrative from the lyrics of the song in how the built environment of Queensbridge projects and its vicinity influenced Nas’ view of the world: one where he jokes with the slicksters selling “broken amps” and uses “mack-10s to defeat foes”- implicit in the whole song is the struggle to survive in an iconic city where the resources and gains seem elusive for those in close proximity to Queensbridge projects.

When George Benson spoke of the bright neon lights on broadway he spoke of the promise of New York, however he quickly points out:

But when you’re walkin’ down that street,

And you ain’t had enough to eat,

The glitter rubs right off and you’re nowhere.

Again we see the tension between aspirations of making it big in New York and the material conditions that sometimes make those aspirations hard to attain.

Teaching the Nineteenth Century

For U.S. History instructors, the Victorian Era of the nineteenth century involves themes which correspond to this tension. The roots of the self-made man, the ideological basis for rugged individualism, and the eventual arrival of the Gilded Age are all lesson units where these songs could be used to help students spatialize the experiences of historical actors. Where were people living? Or a better question is where did their circumstances force them to live? How would such environments affect how they saw themselves in the world? Having discussions with students about historical actor’s conception of place, agency and decision-making brings them closer to understanding not only the actors themselves, but the worlds that these historical actors contended with.

The places these historical actors inhabited shaped their views of the world, thus influencing actions. These actions collectively gave way to wider historical impulses such as migration, expansion, displacement, resettlement and other phenomena. Students can then trace the contours of historical actor, place, condition, and action.

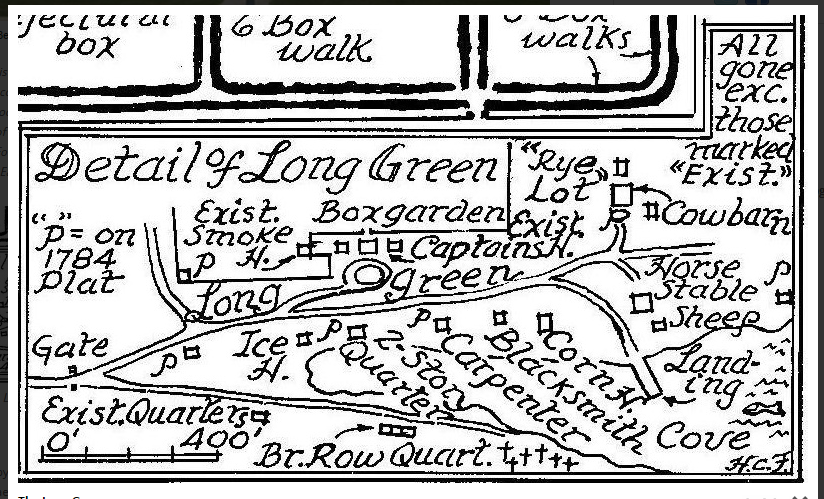

In imagining the conception of place we can use the example of the Long Green, a map by Henry Chandlee Forman of the plantation landscape of the Wye House. Frederick Douglass referred to landscape in his biography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave. This setting served as the backdrop of degrading conditions of enslaved life. [3]

Viewing the Long Green is an interpretive opportunity that allows us the ability to picture and conceptualize the spaces that Frederick Douglass saw daily, however the pictorial view of the landscape alone is not enough. Douglass’ writings tell us much more and bring home a more complete picture of enslaved life.

Historical analysis is expanded through critical geography. Pedagogical tools such as songs about place provide a useful tool to distilling the life narratives of place. Instructors looking for ways to provide students with a more critical reading of spatial analysis and thinking do well to employ music about place.

[1] Robert J.Helfenbein, “Space, Place, and Identity in the Teaching of History: Using Critical Geography to Teach Teachers in the American South”, Counterpoints, Vol. 272, Social Studies—THE NEXT GENERATION: Re-searching inthe Postmodern (2006),114.

[2] Kirsten Simonsen, “Bodies, Sensations, Space and Time: The Contribution from Henri Lefebvre”, Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography, Vol. 87, No. 1 (2005), 6.

[3] “The Lloyd’s Place”, http://beautifulswimmers.tumblr.com/post/55887141375/the-lloyds-place (accessed June 15, 2016).

thanks for this post – really helpful for me!

Thank you so much! I am very glad this post was helpful to you.