Today’s guest post results from a roundtable at the annual meeting of the Society of Historians of the Early American Republic. This roundtable sought to explore how instructors can integrate Carribean history when discussing the early republic. Two of the participants, Anne Eller and Rob Taber have synthesized the conversation for us here.

Anne Eller is an associate professor of history at Yale University. Her first book We Dream Together: Dominican Independence, Haiti, and the Fight for Caribbean Freedom focuses on the reoccupation of the Dominican Republic by Spain in 1861 as well as the popular anti-colonial movement that followed. At Yale, she teaches courses in colonial and modern Latin American and Caribbean history, Caribbean political thought, imperialism, Atlantic history, and the African Diaspora.

Robert D. Taber is an assistant professor of history at Fayetteville State University, the oldest public Historically Black University in North Carolina, where he teaches Latin American, African American, US, and World history. His work has appeared in The Latin Americanist and History Compass and he is an editor for Age of Revolutions. Taber is co-editor (with Charlton Yingling) of Free Communities of Color and the Revolutionary Caribbean and he is currently completing “Family, Slavery, and the Haitian Revolution,” which centers women of color’s experiences in a re-examination of colonial and revolutionary Haiti.

The Caribbean in the US Survey: Sustaining a Dialogue

United States and Caribbean history share deep ties. For teachers of the US to 1865/1877 survey, however, textbooks often only briefly mention the Caribbean after Columbus’s arrival to the Lucayos and Ayiti. For instructors who want to teach foundational connections, this post offers some points of entry for integrating the Caribbean into the U.S. survey. The idea is not to cram “Caribbean facts” into already-full lectures, but rather to offer entry points to broaden students’ frames of reference and deepen their awareness of United States’ history as part of much larger, entangled stories. Here, then, is a chapter-by-chapter guide of how the Caribbean might be brought into the early U.S. survey. The chapters here are from James Oakes et al., Of the People: A History of the United States, 3rd edition (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), but instructors can implement examples with other texts.

Worlds in Motion (1450-1550):

In Caribbean history, just as in U.S., myths of total devastation of native societies after European contact once prevailed. Indeed, hundreds of thousands died, due to disease, the strain of forced relocation, and warfare. However, asking students to reflect on a list of Taino (Arawak) words spoken in contemporary US culture may surprise them. Some may be familiar—barbecue, tobacco, potato, papaya, maize, iguana, hurricane, hammock, canoe, cannibal—and others perhaps less so—caiman, cay, ceiba, guava, savanna, cacique, cassava. In the first days of class, they provide a point of departure to explore cultural survivals, continuities, and lesser-known narratives of Caribbean resistance that have had hemispheric resonance. Studies of responses to Spanish colonialism in Florida also offer perspective. Slavery began immediately, as this interactive resource highlights. Enrique’s revolt (1519-1533) emphasizes how Native and trafficked African people contested European colonial schemes at once.

Colonial Outposts (1550-1650) and The English Come to Stay (1600-1660):

In the earliest decades of colonial expansion, the English jockeyed for moral superiority over other empires and control over new territories simultaneously. Caribbean ambitions shaped English plans, as Richard Haklyut’s proposal to Queen Elizabeth makes clear. The “Black Legend” describing the cruelties of Spanish colonialism should be analyzed in light of English desires for their own expansion into Caribbean territories. Discussing the imperial intent behind a familiar phenomenon — Caribbean piracy — can be eye-opening for students. Beyond the fables, raid attempts, or the seizure of the Spanish silver fleet, the English conquest of Jamaica highlights major, and permanent, expansions of English empire that was rooted precisely in Caribbean battles.

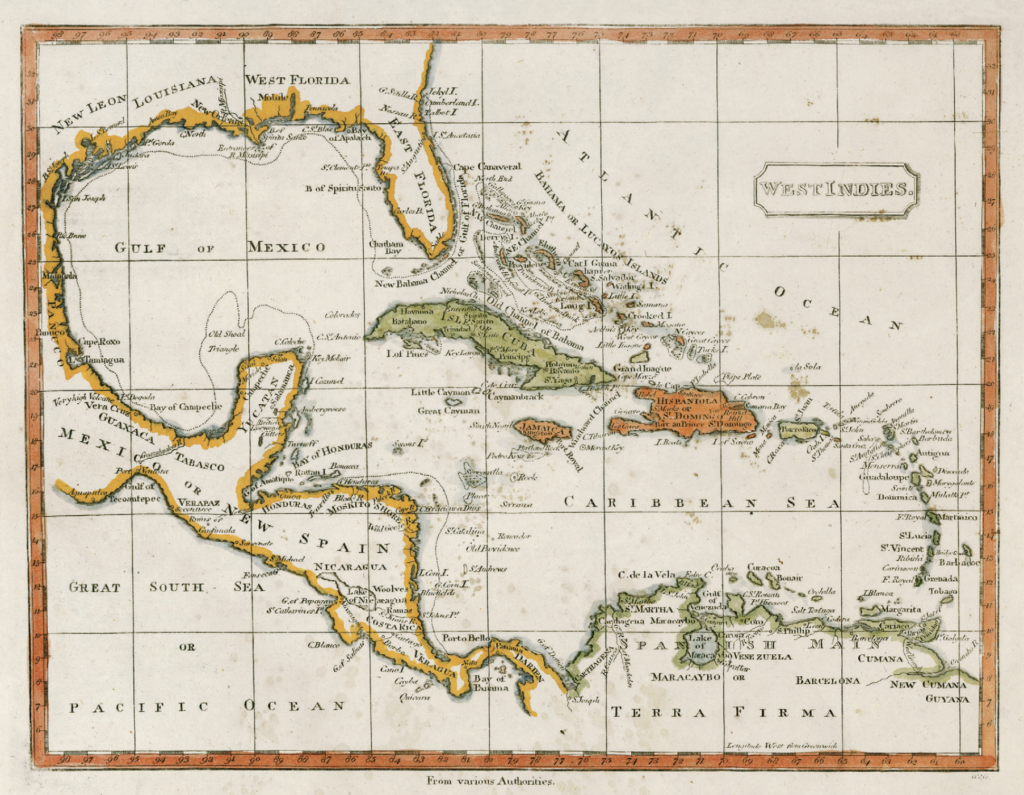

Enslavement, plantation production, and the solidification of anti-black racist narratives, laws, and practices knitted the early English colonies to each other. “Enslaveability” narratives had Caribbean roots and began by the 1500s. The inherent contradiction between humanitarian concern and profit-taking is clearly seen in the original seal of the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Other Caribbean connections include the Caribbean itinerary of John White, the first to report the disappearance of the Roanoke colony, the introduction of Trinidad tobacco into Virginia by John Rolfe, and the Puritan colony on Providence Island. Students might follow #VastEarlyAmerica or engage in this map activity developed by Ben Park and expanded by Rob Taber to visualize how the eastern seaboard colonies were just a small piece of European and Native activities during this period.

Continental Empires (1660-1720) and The Eighteenth Century World (1700-1775):

In this period, networks and foundations relating to Caribbean plantation slavery became even more directly formative of the northern English Atlantic colonies. Following the personal journey of Tituba offers one entry point into the connections between English exploitation of Barbados and the establishment of South Carolina. A number of other works concentrating on the foundations of plantation slavery and the lived experience of those enslaved in Barbados, and connections between Barbados, Jamaica, and South Carolina will be of interest to students. Prominent colonists in British North America had and hid Caribbean ties. Throughout these decades, considering the relationship of Spanish Florida and New Orleans to the English North American colonies and to the Caribbean highlights entangled imperial connections for students.

Conflict in the Empire (1713-1774) and Creating a New Nation (1775-1788):

By the 1760s, the economic interconnection of Britain’s North American colonies and Caribbean colonies were very much intertwined, as was Britain’s geopolitical strategy. During fighting in North America, Britain simultaneously attacked and occupied Havana in 1762. Students might also reflect on why only some British colonies rebelled during the Revolutionary War within the decade. While very much connected to the other colonies, elites of the plantation societies like Jamaica and Barbados were often absentee, and their primary investment was order, repression, and profit. Residents of the French Caribbean participated in the conflicts via trade and military service in the American Revolution. Additionally, possibly the first African American missionary to Jamaica, George Liele, marks the beginning of a sustained religious dialogue with the Caribbean.

Contested Republic (1789-1800) and A Republic in Transition (1800-1819):

When teaching comparative revolutions of this era, the Haitian Revolution is at last receiving the attention it deserves as a profound social and political revolution and world historical event. Multiple works address different aspects of the political impact the Haitian Revolution had on U.S. soil. In addition to this profound and diffuse political impact, few students will know how the Louisiana Purchase was directly linked to Napoleon’s determination to subjugate the rebels in Saint-Domingue/Haiti. A profusion of Dominguan/early Haitian migrations to different parts of the U.S. ensued. The tremendous feat of the Revolution raises questions for students about the nature of comparative revolutions; Haitianist scholars have offered excellent analyses of the interconnectedness of the revolutions as well.

Jacksonian Democracy (1820-1840) and Reform and Conflict (1820-1848):

In this period, including the Caribbean broadens students’ understanding of key struggles over slavery and voting rights in the United States, as men of color lost their rights in several states and responded through political organizing, including petitions. Colonization was always a controversial topic; one contingent of free people of color choose to migrate to Haiti rather than participate in the American Colonization Society’s plans for Liberia. The Baptist War in Jamaica terrified US slaveholders and pushed emancipation forward in the British Caribbean. British emancipation made Canada a potential destination for people self-liberating from slavery in the US, and the larger political impact of emancipation in the British Caribbean and Haiti was enormous.

Manifest Destiny (1836-1848) and The Politics of Slavery (1848-1860):

Teaching antebellum politics necessarily includes the Caribbean. Scholars have described U.S. slaveholders’ Caribbean ties and ambitions. Two large territories, Cuba and the Dominican Republic, were the targets of annexation and filibuster campaigns. The designs on Cuba are more broadly discussed. So, too, are the migration movements to Haiti in the early 1820s and 1860s. Lesser known, but representative of the imperial hubris of the age, are U.S. designs on Santo Domingo. Activist filibusterers such as Jane McManus Cazneau leave a trail for students to analyze; one U.S. writer insisted that gold virtually sprouted in the rural countryside. “St. Domingo” — usually Haiti, although with some imprecision also including the Dominican Republic — remained an important specter and promise. The Haitian state funeral for John Brown offers one concrete example of Haiti’s anti-slavery leadership.

A War for Union and Emancipation (1861-1865) and Reconstructing a New Nation (1865-1877):

The political ferment of the U.S. Civil War included a number of hemispheric developments: the US finally recognized the independence of Haiti and Liberia (1862); Spain annexed the Dominican Republic, and the French invaded Mexico. Stories of the USCT and other grassroots mobilizations against the Confederate rebellion offer comparisons with freedom movements across the 19th-century Caribbean. The Morant Bay Rebellion prefaces the political retrenchment that came with the collapse of Reconstruction, and many Americans discussed rebellions against slavery in Cuba’s Ten Years’ War. U.S. exports to various islands steadily increased in these decades, prefacing the greater imperial involvement that was yet to come. Finally, growing Caribbean migrant communities began to transform U.S. cities.

One African American visitor to the Dominican Republic commented in 1860, “the stars of the tropics are the guiding stars of the age.” Including the Caribbean in the early US survey allows students to expand their imagination to keep pace with political contests that extended to the whole hemisphere.