I often receive comments on my evaluations for the US I survey that I spend too much time on religion. I explicitly discuss religion in quite a few cases throughout the semester – colonial missionaries, Calvinists and Quakers in 17th c. New England, the First Great Awakening, abolitionism, new 19th century religions, and Lincoln’s second inaugural address – but I also know that if anything, I discuss religion too little, given its importance to the people we’re talking about. But teaching religion in the US survey is difficult, for a lot of different reasons. In this post, I want to explore some of the struggles I have teaching it, and offer some approaches I’ve found successful.

A while back, I read Jolyon Baraka Thomas’ piece Teaching True Believers, and responded with my own thoughts: Teaching religious n00bs and skeptics. Where Thomas talked about struggling to get students with strongly-held beliefs to see religion as “a social construction or an anthropological conceit or a legal category bearing geopolitical effects,” I reflected on the difficulties of teaching the history of religion to students “who have little framework for understanding religion or belief but nonetheless have very fixed ideas about how religion operates.”

Both in the comments on the piece itself, and on Twitter, many scholars of history and religious studies expressed shock at the idea that students could be so ill-informed. Many put it down to geographical differences; some parts of the country are just more religious than others, and therefore some students more prepared to talk about it.

There’s something to that argument, but I think that something more specific is at play. Did students grow up in a place where religion was understood to be a public matter (at least if you belonged to the dominant religion) or a more private matter? I’m not saying that there’s anywhere in the United States that’s free of civil religion or laws that reflect the views of historically-dominant religions, but that in parts of the country where students don’t see religious belief, it might be easier for them to think it’s not there. As a result, even the moderate amount of discussion time we spend learning about American religious beliefs in the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries seems like so much religion.

This presents a particular kind of challenge in teaching. It’s not like religion is the only thing we teach where students have to be persuaded that it’s worth thinking about, but for me, teaching in the Northeast, it’s also something where many students have almost no pre-existing framework to hang new analysis on, and the framework they do have largely consists of “religion was for people in the past and is a marker of backwardness.” I imagine this is the case for a lot of historians. But I can’t give up on teaching it. And so, in my US I, we draw a lot of family trees to map out the branches of Christianity. We talk about the contours of antisemitism. We define terms: “heathen,” “Papist,” “evangelical,” “denomination,” “salvation.” We draw more family trees.

And we talk about the assumptions students do have, and where those assumptions come from. Many of my students, when asked to associate “predestination” with Catholicism or Protestantism, pick Catholicism; their vague understanding of Catholicism as authoritarian and restrictive, drawn from popular culture, leads them to assume that, of the two options, it’s more likely to believe people have no control over their salvation. Having these discussions, and asking students to talk about what they think of when I say “evangelical,” or “heathen,” or “revival,” not only helps us with our analysis, but helps students realize that perhaps religion is part of their daily lives, and the lives of those around them. That, in turn, opens them up to thinking about its role in the daily lives of the people we are studying.

It’s hard, and I don’t know how much I accomplish each semester. Getting students to put themselves in the mindset of people in the past is the central challenge of teaching history, but I think it’s important to acknowledge that it’s easier for students to inhabit the mindset of a slaveowner (almost too easy, sometimes) than the mindset of a white Methodist woman in the 1830s. Racism is a familiar framework to them. Religious belief is not.

One approach that has worked is asking students to think about religious belief in relation to another system of belief that they generally agree is real and valid: science. Coming into the classroom, my students assume the two systems of belief are completely separate, and stand in opposition to one another. They also think one of these systems is historical, while the other stands outside of history. I’m sure you can guess which is which. But having students think about both as ways of understanding the world, particularly the parts of it that seem confusing, can help students be a little more open to considering religious belief, rather than writing it off as people in the past being dumb and superstitious.

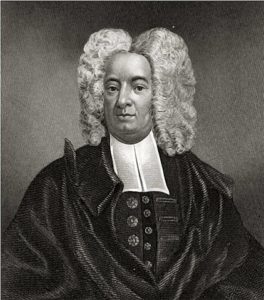

Earlier in my teaching career, I had students read pro- and anti-inoculation letters from 1721 Boston, Cotton Mather in support of inoculation and Dr. William Douglass in opposition. Douglass condemned inoculation, practiced by “Old Greek Women,” as ineffectual, and sarcastically said he would leave it to ministers to determine whether it was appropriate to trust the “extra groundless Machinations of Men” over “our Preserver in the ordinary course of Nature…the all-wise Providence of GOD Almighty.” In his response, Mather supported inoculation, calling its discovery and practice “the gracious discovery of a Kind Providence.” Students either told me the two men said the opposite of what they said, or told me that the doctor was right – inoculation is dangerous and bad. These students were not anti-vaxxers, but rather so committed to the idea that science and religion were separate, and the idea that science=Truth, that it was almost impossible for them to think critically about the words they were reading. After several frustrating semesters, I gave up on those documents.

But the experience helped me see the ways that pushing at these assumptions could be fruitful. Now, I assign a few entries from John Winthrop’s diaries, very early in the semester, that allow me to push right away. The most useful one is about a storm:

There was so violent a wind at S.S.E. and S. as the like was not since we came into this land. It began in the evening, and increased till midnight. It overturned some new, strong houses; but the Lord miraculously preserved old, weak cottages. It tare down fences, – people ran out of their houses in the night, etc. There came such a rain withal, as raised the waters at Connecticut twenty feet above their meadows, etc.

The Indians near Aquiday being pawwawing in this tempest, the devil came and fetched away five of them.

Quite often, students tell me what they think really happened: the houses that fell down were just poorly built, because people back then weren’t very good at building things. I then ask them whether people at that time were able to build cathedrals, or build ships and sail around the world. They then have to confront the fact that their “scientific” explanations for the wonders Winthrop recorded make less sense than saying “God did it.” They were doing what Winthrop was doing: trying to make sense of a strange situation using the ideas they had about the true way the world works. It helps them think about why religious belief might matter to someone, and has the added bonus of getting them to think historically about science.

All this being said, I don’t think people who teach in “more religious” parts of the country have it easier. Sure, their students might have a framework where mine have none, but that framework itself needs to be put under a lens. In my classroom, every student who’s ever asked if Catholics were Christians has been genuinely confused about a set of relationships they were confronting or considering for the first time. I’ve never had a student argue that Catholics aren’t Christian.

And, as a recent Pew survey shows, lots of Americans don’t understand or believe what they’re supposed to believe, given their self-identified denominational affiliation. When students argue that people in the past seemed to behave in ways that contradicted what they claimed to believe, we can point to the fact that many current Protestants belong to denominations that believe in sola fide but don’t believe in it themselves.

Teaching religion in the US survey is hard, but we need to keep trying. If you avoid it because students struggle with it, rethink that choice. If you consciously or unconsciously teach it as backwards superstition, rethink that choice as well. If you teach it but get frustrated, keep trying, and use meta-cognitive approaches that bring unspoken assumptions to the surface.