Few topics evoke such genuine intellectual curiosity amongst my overly achievement conscious students as the American Civil War. As a teacher, this proves fortunate, given that our study of the late antebellum period and war years typically falls after a ten-day break for the Thanksgiving holiday and before an eighteen-day winter vacation. As you might imagine, I tend to lose some sleep over the pacing and content coverage concerns associated with our institution’s calendar this time of year. Luckily, the glut of both traditional historical scholarship and popular history surrounding the Civil War era is such that the opportunities to engage high school students in meaningful ways across the spectrum of history seem almost limitless. While we adhere to a schedule of traditional text readings, the festive nature of the just over two week-long interlude between breaks encourages some outside of the box assignments and innovative assessment opportunities.

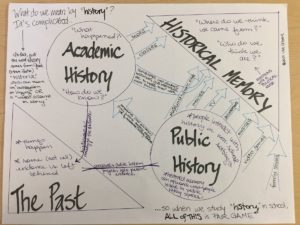

But what do we mean by the spectrum of history? As I considered the diverse array of source material I sought to incorporate in the class, I was left wanting some way of framing this diversity, to allow the students to appreciate the various ways they might engage with our understanding of the Civil War. And in a moment of serendipity and timeline clarity I haven’t encountered in over a year, Twitter came to the rescue. Educator Lisa Gilbert’s (@gilbertlisak) tweet, containing a visual examination of the connections between academic and public history, as well as the differences between the past and historical memory, dropped into my feed and I scrapped my original post on single-point rubrics using the AHA’s History Discipline Core Document. For many high schoolers, there is all too often an understanding of history in the purely academic sense. That is a traditional textbook, secondary source, or class lecture and discussion format. In some basic, higher-level instances, indeed, even in recent changes made to standardized testing, there is an intentional analysis of various forms of evidence. We engage in “Academic History” by tackling chapters in our digital textbook but also by reading portions of monographs from the likes of Drew Gilpin Faust’s, This Republic of Suffering, James MacPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, or Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom. It’s important for them to engage with this type of history, for here they see very tangible ways in which historians wrestle with evidence from “The Past.” But we also get students to wrestle with “The Past” in their own way, primarily through an in-depth exploration of the outstanding Valley of the Shadow archive. It’s when we shift to the areas of “Public History” and “Historical Memory” that students begin to appreciate the amount of content that abounds all around them. The debate over Confederate monuments has been omnipresent since our very first day together, thus engaging the important questions of “Who do we think we are?” and “Where do we think we came from?” related to Historical Memory. But through examinations of the ways people interact with history outside of an academic setting, students begin to appreciate the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) ways the public comes to know the past. When listening to and analyzing the lyrics of The Band’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”, practicing visual literacy in assessing the film Glory, or debating the intentions and appropriateness of HBO’s Confederate, students gain a newfound appreciation for the power of alternative historical mediums that lay outside of the classroom.

For many high schoolers, there is all too often an understanding of history in the purely academic sense. That is a traditional textbook, secondary source, or class lecture and discussion format. In some basic, higher-level instances, indeed, even in recent changes made to standardized testing, there is an intentional analysis of various forms of evidence. We engage in “Academic History” by tackling chapters in our digital textbook but also by reading portions of monographs from the likes of Drew Gilpin Faust’s, This Republic of Suffering, James MacPherson’s Battle Cry of Freedom, or Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom. It’s important for them to engage with this type of history, for here they see very tangible ways in which historians wrestle with evidence from “The Past.” But we also get students to wrestle with “The Past” in their own way, primarily through an in-depth exploration of the outstanding Valley of the Shadow archive. It’s when we shift to the areas of “Public History” and “Historical Memory” that students begin to appreciate the amount of content that abounds all around them. The debate over Confederate monuments has been omnipresent since our very first day together, thus engaging the important questions of “Who do we think we are?” and “Where do we think we came from?” related to Historical Memory. But through examinations of the ways people interact with history outside of an academic setting, students begin to appreciate the subtle (and sometimes not so subtle) ways the public comes to know the past. When listening to and analyzing the lyrics of The Band’s “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down”, practicing visual literacy in assessing the film Glory, or debating the intentions and appropriateness of HBO’s Confederate, students gain a newfound appreciation for the power of alternative historical mediums that lay outside of the classroom.

And in doing so, they begin to understand the inherent value of the study of history, and why it’s so important that historians make their work more public. It’s as though the Confederates aren’t in the attic anymore, as Tony Horwitz once suggested. Instead, they’re right next door.