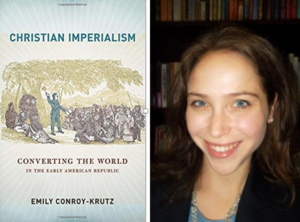

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Emily Conroy-Krutz, Associate Professor of History at Michigan State University, the author of Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic (Cornell University Press, 2015).

Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic is a book about empire, religion, and the ways some Americans of the early republic tried to imagine the role that their new country could and should play in the world. It tells the story of missionaries of the American Board of Foreign Missions in the decades between the 1790s and the 1840s as they planned and built their missions throughout the world. I argue that American evangelical Protestants of the early nineteenth century were motivated by what I have called “Christian imperialism,” an understanding of international relations that asserted the duty of supposedly Christian nations, such as the United States and Britain, to use their colonial and commercial power to spread Christianity and “civilization.” Importantly, this was an imagined imperialism that, as missionaries would find when they went out into the field, did not match up with the political realities they met in and around the Anglo-American imperial spaces that they expected would be an important partner in their work.

Christian Imperialism: Converting the World in the Early American Republic is a book about empire, religion, and the ways some Americans of the early republic tried to imagine the role that their new country could and should play in the world. It tells the story of missionaries of the American Board of Foreign Missions in the decades between the 1790s and the 1840s as they planned and built their missions throughout the world. I argue that American evangelical Protestants of the early nineteenth century were motivated by what I have called “Christian imperialism,” an understanding of international relations that asserted the duty of supposedly Christian nations, such as the United States and Britain, to use their colonial and commercial power to spread Christianity and “civilization.” Importantly, this was an imagined imperialism that, as missionaries would find when they went out into the field, did not match up with the political realities they met in and around the Anglo-American imperial spaces that they expected would be an important partner in their work.

The book opens with the question of how missionaries chose where they were going to go. With the whole world to choose from, what made a particular place seem like a good place to start a mission in the 1810s, 1820s, or 1830s? I argue that if we look carefully at the decision-making process of these missionaries, we can see what I’ve called a “hierarchy of heathenism” that ranked the world according to its perceived status of civilization (including ideas about gender, education, commerce, and work) and proximity to Anglo-American commercial and colonial power. The book then follows missionaries as they went out into the mission field and began their work. Because of my interest here in American ideas about empire, the places that receive particularly close focus in later chapters are sites of different sorts of imperial encounter: British India; the Maryland Colonization Society’s colony at Cape Palmas, Liberia; the Cherokee Nation; Hawaii; and Singapore, where US missionaries proposed (but did not create) a new American colony in the 1830s.

As a whole, the book contributes to a few different historiographical conversations—it is a “global turn” book for early and religious history, and a “religious turn” book for the history of foreign relations/US and the world. In the classroom, that should translate to the book’s usefulness in a few different types of courses. If you’re teaching American foreign relations, this book will help you get your students thinking about American engagement with the world in the early nineteenth century and will help you ask questions about which type of actors are important for how we tell the story (or stories) of American foreign relations. If you’re teaching American religious history, this will help them think about the connections between religion and American politics as well as about how American Christians thought about people of other religions. If you’re teaching the survey or a course on the early republic, this will help your students explore American conceptions of empire in this era, with discussions of (for example) settler colonialism, Anglo-American cooperation and competition, and the colonization movement.

Since assigning a full book isn’t always an option, TUSH asked which chapters would work best to assign on their own. If you’re looking for a single chapter to use, “Hierarchies of Heathenism” would be a good choice. This is the first chapter in the book, and it provides an overview of the many different types of places where missionaries went, and the ideas about civilization, gender, race, and empire that structured their decision-making. You can quickly get a sense of the global imagination of American missionaries at this time and the cultural, imperial, and commercial networks that shaped where they wanted to and could go. (And if you’re wanting to talk about missionaries alongside other types of Americans abroad, I think this chapter pairs very nicely alongside the first chapter of Brian Rouleau’s With Sails Whitening Every Sea). Later chapters in the book could also be useful as stand-alone assignments, depending on what kind of class you’re teaching: there are individual chapters on Anglo-American connections in India, on education and conversion in India, on settler colonialism in the Cherokee and Hawaiian contexts, on Indian Removal and missionary politics, on the colonization movement to Liberia, and on ideas about colonization in Singapore. When I’ve Skyped in to classroom conversations about the book, the chapter on education and conversion often gets a bunch of questions and seems to have sparked interest.

If you wanted to incorporate material from the book into lectures and direct your student readings towards relevant primary sources, there are many accessible options that could work. The book relies on missionary papers in the United States and England, many of which are archival manuscripts, but there are some digitized sources that could be incorporated into classroom discussions around themes raised in the book. Missionaries were incredibly prolific (print culture was an important engine of fundraising and of spreading news about their work), and students can easily access digitized editions of memoirs, periodicals, and annual mission board reports. The ABCFM’s monthly magazine, alternately titled the Panoplist, Panoplist and Missionary Herald, or Missionary Herald (depending on the years), can be found online through the American Periodical Series, with some volumes also available on Google Books (here). I think these magazines are a particularly fruitful type of source for students to work with because they give a sense quickly of one of the major points of the book: that missionaries really did try to present the whole globe to Americans at home. While readers might have been personally more interested in one place or another, a missionary magazine would quickly survey the state of things around the world, creating important links for readers between Asia, Africa, the Pacific, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. If you want to use missionaries to provide a deep dive into American ideas about particular locations, the book makes use of missionary memoirs and ethnographic writings that students might find fruitful for discussion: memoirs of Harriet Newell could both provide windows into early American ideas about India while also opening up important conversations about women and gender, or you might use parts of John Leighton Wilson’s history of West Africa to talk about American understandings of Africa in this period.

It’s my hope that professors and students find Christian Imperialism to be a helpful text as they work to bring some of the stories that haven’t always been easily incorporated into our survey-level narratives of US history: stories about American history beyond the North American continent before 1898; about the complicated connections between religious, political, and commercial ambitions in shaping American engagement with the world; and about the ways that Americans of the early republic thought about empire, civilization, race, and gender around the world.