During the spring of 2016 I began looking for a program that would help me to improve my ability to teach writing in the history classroom. What I found wasn’t exactly what I thought it was, but something much better. During my first Google search for “Teaching Historical Writing” I found information on the Bard College Institute for Writing and Thinking (BIWT), and their summer writing workshops for teachers.

Quoting from their promotional material “The Institute for Writing and Thinking seeks to enrich and deepen learning in all disciplines with programs that focus on the role of writing in teaching and learning. The Institute offers secondary, college, and university faculty a place to renew themselves intellectually, imagine and practice new teaching strategies, and envision classrooms in which writing is a catalyst for learning in all subjects…” My session during the summer of 2016 was a case study using BIWT techniques and historical document analysis.

In his 2001 study Historical Thinking and Other Unnatural Acts: Charting the Future of Teaching the Past, Sam Wineburg promotes teaching our students primary source analysis and critical reading through training and explicit modeling of those actions. Wineburg and others have for some time promoted training our students in document analysis and critical reading as one of the necessary skills of the historian. It is my assertion that in addition to critical reading, writing about the documents, essays, and other historical texts that make up the field of history is also crucial.

Many of my two-year college students arrive in my classrooms lacking solid writing skills. Based on this fact I have worked to integrate the informal in-class writings techniques I learned at the BIWT workshop to provide increased practice and training. These forms of informal writing are done both in preparation for, and quite independently of, formal writing. It is freewriting, unconstrained by any need to appear correctly in public. Yet, it is still reflecting and questioning. This is probative, speculative, generative thinking that is written in class or at home to develop the language of learning. Generally, it is not graded. Parts of it are often heard in class, as a means of collaborative learning, not of individual testing. Its basic purpose is to help students to become independent, active learners by creating for themselves the language essential to their personal understanding.

The essence of the BIWT program is distilled in the book Writing Based Teaching: Essential Practices and Enduring Questions edited by Teresa Vilardi and Mary Chang. My key takeaway from this book is that these in-class writing exercise are meant to help students to become more comfortable with writing by simply giving them more practice and making it OK for writing to be imperfect. Here the practice of writing and the repetition of document analysis called for by Sam Wineburg come together. When I talk to colleagues about this the same questions arise. Where is there time to fit more writing into my teaching? I don’t want to give up coverage of content to become a writing teacher, how would this work in the history classroom? How do I pay attention to students’ language when I teach history? How can I maintain academic standards for critical thinking if I make writing more central to my curriculum?

What I argue is that using these techniques: 1) actually promotes critical thinking, 2) does not require that you pay attention to language or become a writing instructor, AND 3) can actually be used to facilitate coverage of historical material through document analysis, student discussion, and when needed mini-lectures on crucial points needed for historical understanding. However, these can’t be a collection of strategies that are pulled out and used occasionally, they must become a practice developed through frequent use and refinement.

So, am I saying, have students write in each class? Well… yes, that is exactly what I’m saying.

In Why Learn History (When It’s Already on Your Phone) Sam Wineburg writes “Like other habits, habits of mind demand repetition, stick-to-itiveness, and exposure to multiple examples where the content changes but the core intellectual moves remain the same” (Wineburg, Why Learn History?, 128). Since critical reading, as well as writing, are the primary “intellectual moves” of the historian, our students must do the same.

I want to address some basic issues of procedure. Whenever you employ these techniques you (the instructor) also need to participate in the writing. Students need to see you engaged and sharing your thoughts and writing as a model of how we as historians think or work through a document or problem. All students need to have the expectation that they will or may be called on to share (except when freewriting). Clearly, this is hardest when you have classes larger than 25 or 30 students. So, planning ahead for a different procedure may be necessary for larger classes. But, for smaller classes it’s best if everyone shares each time these techniques are used. For everyone when they are sharing their writing, they need to read exactly what they wrote. No preamble, no editing, no explanation of what’s there. It is expected that everyone is providing unvarnished material and errors, or awkward writing should be expected. That’s OK, this is practice and it will improve over time. The added advantage of this technique is that it helps to foster discussion. Even the student most averse to public speaking can participate if they are simply reading what they have written.

A list of informal writing examples (some of which you may already use) includes: Freewriting, Focused Freewriting, Attitudinal Writing, Metacognitive Process Writing, Listing Questions, Creating Problems, Quotation-Paraphrase-Summary Writing, and various forms of Writing to Read strategies. One powerful writing to read strategy is the double-entry or “dialectical” notebook: recording and reporting what a reading says and, in a facing column or page, responding to the text. Dialectical notebooks integrate attitudinal writing, questioning, summarizing, and process writing.

The example that I would like to share is the most time consuming, but often the best form of informal writing when examining historical texts or secondary source interpretations. You may or may not be familiar with Dialectical Notebooks, but here is how I use them in my class based on the BIWT model.

Students are given a reading. This could be something longer that they are expected to read at home prior to class, or a shorter piece or excerpt that they read in class. Either way you should direct them to underline and/or annotate what they find interesting and puzzling, as well as any aspects of the material you want them to focus on. In class they are asked to take a piece of notebook paper divided into three columns width-wise.

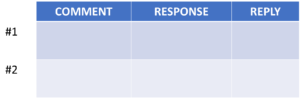

In class, have students choose two or three brief passages in the text to comment on and highlight or number those passages. After numbering the chosen passages in the margin of the text complete the following using the chart below. Comment: place corresponding number in the left-most column of the notebook and write comment for each excerpt. Next, Response: Students now exchange both the text and notebooks with a partner. Each student responds to the numbered portion. of their partner’s comments in the middle column. And finally, Reply: Partners return texts and notebooks to one another and reply to the responses in the third column, exchanging notebooks a final time to read replies.

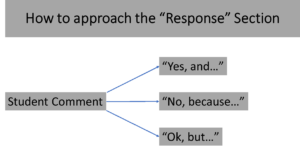

Early in the course (and sometimes throughout it) students have trouble figuring out how to approach the Response section. Here is a model that I give them to help. After reading the excerpt and comment they can choose one of three avenues. “Yes, and…” to agree with the comment and further the thinking. “No, because…” to disagree and explain why. Or “OK, but…” if they partially agree but believe the comments needs further clarification. Below is how I generally explain it to students.

My preliminary analysis is that students do participate and complete these informal writing assignments. And the writing and sharing of it have increased the amount of class participation. For the stronger students they often grow into the exercise and approach the reading and writing about our documents in unique ways. While those students that need more time to become proficient in these tasks can use the scaffolding provided by the BIWT techniques to remain engaged in the class. Any long term or more detailed impacts of these methods will require further student in a more rigorous and in-depth way. Nevertheless, I can say that my classes have improved.