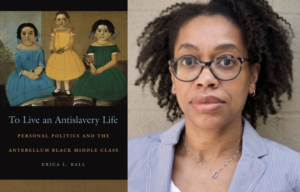

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Erica L. Ball, Professor of History and Chair of Black Studies at Occidental College. Dr. Ball is discussing her book To Live an Antislavery Life: Personal Politics and the Antebellum Black Middle Class (Georgia 2012).

Can you give us a brief overview of your book’s argument, narrative, and historiographical contribution?

To Live an Antislavery Life: Personal Politics and the Antebellum Black Middle Class explores the abolitionist activism and literary culture of Northern free Blacks in the decades before the Civil War. I examine African American print culture, analyzing the published proceedings of antebellum colored conventions, the editorials, fiction, and advice literature printed in antebellum Black periodicals like Freedom’s Journal, the North Star, and the Anglo-African Magazine, and narratives by famous activists such as Frederick Douglass. I find that in addition to using print culture to advocate for Black freedom and equality, antebellum Black public figures also regularly offered advice on what their readers should wear and eat, shared tips on how to raise a family, and advocated for the importance of education. I ended up focusing on these texts in an effort to shed light on the ways that larger abolitionist concerns shaped and defined an emergent Black middle-class culture.

To Live an Antislavery Life: Personal Politics and the Antebellum Black Middle Class explores the abolitionist activism and literary culture of Northern free Blacks in the decades before the Civil War. I examine African American print culture, analyzing the published proceedings of antebellum colored conventions, the editorials, fiction, and advice literature printed in antebellum Black periodicals like Freedom’s Journal, the North Star, and the Anglo-African Magazine, and narratives by famous activists such as Frederick Douglass. I find that in addition to using print culture to advocate for Black freedom and equality, antebellum Black public figures also regularly offered advice on what their readers should wear and eat, shared tips on how to raise a family, and advocated for the importance of education. I ended up focusing on these texts in an effort to shed light on the ways that larger abolitionist concerns shaped and defined an emergent Black middle-class culture.

To Live an Antislavery Life shows that Black activists and writers consistently urged their audiences to internalize their political principles and to interpret all their personal ambitions, private familial roles, and domestic responsibilities in light of the abolitionist movement and larger Black freedom struggle. To put it another way, I argue that antebellum Black activists urged their readers to embody the abolitionist agenda by living what the fugitive Samuel Ringgold Ward called an “antislavery life.” As I see it, African American writers characterized true antislavery living as an oppositional stance rife with radical possibilities, a deeply personal politics that required African Americans to transform themselves into model husbands, wives, mothers and fathers, to make themselves into self-made men, and to follow in the footsteps of freedom fighters and revolutionary figures from Haiti to Hungary. In the process, antebellum Black writers crafted a set of ideals – simultaneously respectable and subversive – for African American readers to embrace and live up to in the decades before the Civil War.

How does your book shape the broadest narratives in American history? How should survey courses in American history reflect the arguments and evidence of your study?

To Live an Antislavery Life contributes to our understanding of United States history in a few key ways. Scholars have shown that advice literature, conduct discourse, and self-fashioning was very important to white northeasterners who were in the process of defining the culture of an emergent middle class in the decades before the Civil War. To Live an Antislavery Life shows that Northern Blacks were also deeply interested in processes of self-fashioning. In fact, they consistently connected their own personal behavior with the fight against slavery and characterized the creation of ideal respectable, virtuous, politically-engaged selves, families and communities as both a right that came along with freedom and, therefore, a personal obligation and duty for free Black men and women. In the decades leading up to the Civil War, Black conduct writers urged every single person of African descent to exert their own agency to live the kinds of lives that rebuked every single proslavery argument of the day. They conceptualized this self-fashioning as the personal and private counterpart to their public abolitionist activism.

What courses commonly taught at the college level besides the survey would most benefit from considering your work?

In addition to the U.S. history survey course, To Live an Antislavery Life works well in African American history courses, especially courses that focus on the history of slavery and the abolitionist movement. The book also works well in courses on print culture, cultural history, and gender and family history.

If instructors were to excerpt a chapter or two from your book, which chapters do you think would be most useful, and why?

Chapter one examines advice specifically directed to young Black courting sons and daughters and newlywed husbands and wives. It shows how Northern free Blacks disseminated advice and explains why they sought to transform themselves into living refutations of the era’s proslavery discourse. I would also recommend chapter five. In this chapter I show how African American writers employed a transnational discourse of revolution on the eve of the Civil War, characterizing those men and women who fought and died for freedom – in Europe as well as the Americas– as exemplary antislavery figures, models of virtue and sacrifice for Northern free Black readers to emulate if they hoped to truly embody their abolitionist principles and bring an end to slavery in the United States.

Many of our instructors have the goal of teaching students both content and methodology. What does your book have to teach us about how historians work? Are there methodological lessons we can learn from your scholarship? Do you have advice for instructors on how we can share those lessons?

It is good for students to know that research is a process. We don’t write a proposal and then go out and simply search for the evidence that proves our hypothesis. Our projects are shaped by the evidence that we find. And sometimes our projects are shaped by happy accidents – by stumbling across the unexpected document sitting right next to the document we were originally looking for. When I began this project, I intended to write a more traditional history of Black abolitionist activism before the Civil War. But as I conducted my research, I kept running into a problem: When I turned to collections like The Black Abolitionist Papers, or antebellum Black newspapers and magazines like Freedom’s Journal, the Colored American, and the Anglo-African Magazine, I always found very clear denunciations of slavery and racism. This, I expected. But I also kept finding tons of additional material: advice on personal conduct, how to dress, how to choose a spouse, how to properly raise a child, how to exercise “female influence” appropriately, what “good books” to read, what behavior to avoid; as well as advertisements for etiquette books on table manners, business conduct, letter writing, etc. And no matter how hard I tried not to be distracted by this material, I was deeply fascinated by this advice literature that was routinely published either alongside or as a part of traditional abolitionist fare.

What is the biggest misunderstanding you feel that students have related to your subject? What do you think is the most effective way of disabusing students of this misunderstanding?

To Live an Antislavery Life argues that the personal politics promoted by African American activists and writers involved far more than engaging in a “politics of respectability” before the gaze of white observers. Rather, it called for elite and aspiring African Americans to embody their resistance to slavery by internalizing their antislavery principles, interpreting their private familial roles and domestic responsibilities in light of the abolitionist campaign, and enacting their abolitionist beliefs in every aspect of their lives, whether in public or in private. In this way, antebellum Northern Blacks anticipated what some scholars today (Ibram X. Kendi, for example) call living an antiracist life. Of course, their conception of what it meant to live an antislavery life in the antebellum era was shaped by the early-nineteenth-century context in which they lived. But the commitment to living lives that facilitated the freedom struggle is, in many ways, similar to the current call to fully commit to the ongoing struggle for freedom and justice in the United States today.