by Nina McCune

This summer has been a whirlwind – one rife with new ideas for various parts of the survey. Most recently, I’ve returned from Savannah, GA where I took part in a one-week National Endowment for the Humanities Landmarks Workshop at the Georgia Historical Society. Throughout the week, we revisited themes of race and slavery and visited sites where this racial and social history lives on. Strong scholarship and supportive camaraderie gave rise to an attendant question in this investigation: how do we meaningfully engage our students in the study of race and slavery since many feel the issue is resolved?

The idea of anyhistory being “resolved” or somehow neatly tied together in the textbook’s narrative is something we all struggle with. American history is so expansive and recent – we sprint every year to “cover” all aspects of the survey. In that haste, we might drop threads and discussions. As historians, however, we are charged to investigate, re-open, and re-examine even the most remote phenomena and events. Moreover, we are ethically bound to tell the stories of those who lived those phenomena and events: in the case of the Atlantic slave trade, colonial/post-colonial American slavery, and the Emancipation of 1865, historians have just begun to tell those stories. It’s only been in the past 20 years or so that the discipline of African American History has exploded with treatments of individuals, plantations, and states actively engaged in pre-Civil War enslavement and forms of post-Civil War freedom.

Yet, many students see the issue of slavery as irrelevant to their generation. After all, series of legal instruments have been repealed and established, apologies made, reparations offered. There is a seeming incongruity between the younger survey student’s willingness to study American slavery and the profound literature evolving on the subject.

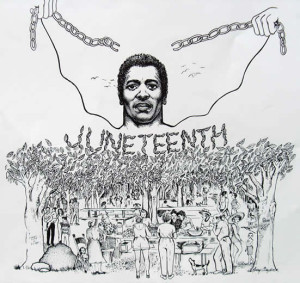

Thus, I return to the framing question: how do we meaningfully engage our students in this study? Clearly, if southern states (especially Texas) still celebrate Juneteenth, this history is not resolved. In the workshop, we visited two Georgia sea islands (Sapelo and Ossabaw – please click on the links to see my photos) where the history of slavery and freedom predominates the landscape. We saw how enslavement was different and unique to the Georgia coast, we learned how urban and rural slavery in these places provided relative autonomy to some slaves, and we met descendants of families who remain on the land to retell the stories. And, although the two islands are now differently used (Sapelo, despite encroachments by the state of Georgia, continues to be the home of descendants of slavery in the geographically small and economically dwindling community of Hog Hammock; Ossabaw, purchased in 1924 by a wealthy Michigan family, struggles to accurately portray the history of enslavement despite the attempts at preserving a few slave cabins, continuously inhabited until the 1980s) – there are fundamental issues of land and land ownership – that extend onto the mainland as well. In other words, place matters in the study of history. Where something happened, it is likely to continue happening. It’s perhaps easy to study something that happened in a particular place because one has proximity to the land and the people.

However, if place matters in the study of history – so must place-lessness. Universal themes of rights, liberties, land – or at least “universal” to the study of the American state – are as important as remembering. How can we make this part of history come alive to students in California, Idaho, or Maine? Such places have no proximity to the Georgia sea islands, to Texas, or to active engagements in American slavery. Are the universal ideas borne out of this experience enough?

I offer you some techniques I learned from this workshop. Please feel free to comment on other ideas you have!

Readings:

- God, Dr. Buzzard, and the Bolito Man by Cornelia Walker Bailey. Ms. Bailey still lives on Sapelo Island, and is a sophisticated advocate for the living preservation of her community. This book is a narrative of her life – students should easily engage in her humor and insights.

- For primary sources, have students read the March 9, 1859 undercover report on the largest slave sale in the United States in Savannah, GA. This is referred to as the Weeping Time, and although the physical structure where the sale took place no longer exists, Georgia Historical Society has erected a marker.

- Other post-Emancipation primary sources are available at the Freedmen and Southern Society Project.

Music:

- Have students listen to “Bid ‘em in” from Oscar Brown, Jr. (this is a freely available YouTube video, however the song is purchasable from iTunesand may be more effective than having visual accompaniment.) We did this several times during our time with Alexander X. Byrd (Assistant Professor, Rice University and author of Captives and Voyagers). Dr. Byrd asked us to keep two columns as we listened to this song: one tracking signs of subjugation, the other tracking signs of agency.

Images:

- Also an idea from Dr. Byrd: examine the background, middle ground, and foreground of Olfert Dapper’s 1686 woodcut “Description of Africa” (or any image from that volume) using non-interpretive language. Describe where figures and shapes are located, their relative perspective and scale, and so on. From there, one could begin an analysis – why would one figure be pouring something for another? Is this breaking trade? If so, how did that practically work in the slave trade? How could this story play out?

this is fantastic!!!

Thanks, Ed! I noticed I somehow messed up the links for the photos. The pictures for Sapelo and Ossabaw Islands are in albums at: https://picasaweb.google.com/114303977036164408865

Nina,

I have been thinking about this, too. How can we give our students even a peice of what we experienced in Savannah? I live in Pennsylvania, which makes it even harder for them to imagine what the south during slavery is like. I am thinking that I may have them look into their own family histories, like Myiti did, or into our local connections to slavery and labor. I doubt there is anywhere in the US that did not in some way at least interact with the slavery question.

But, how can we transport them to the Sea Islands is another question. Photo? Video? Interactive maps? Perhaps our own descriptions of place are going to be enough?

http://atlnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/atlnewspapers/view?docId=news/awi1859/awi1859-0037.xml&query=negro sale&brand=atlnewspapers-brand

I did a quick search and found an Atlanta paper with a mention of the Weeping Time sale. It is the in the sixth column, halfway down the page. It says that the buyers are “spirited.” Might be a good comparison piece for the other article.