I had the recent opportunity of facilitating a GIS teaching session for the Digital Humanities Bootcamp at the University of Nebraska Lincoln in April of this year. The Digital Humanities Bootcamp is put on by UNL’s Center for Digital Research in the Humanities and explores technologies and recurrent tools in the DH world in an effort to provide participants with hands-on training as well as theoretical concepts in the digital humanities field.

As a former adjunct now second year PhD student I was very excited to get back in front of the classroom again. The most important element in preparing the content was ensuring that my students walked away with a vested interest in engaging the spatial humanities in their scholarly work. I wanted my students to explore how we trace where people go, what influences movement, the ways that spaces are choreographed, how experiences are embedded in the landscape, and the forces in society that impact and impede movement.

To begin I wanted students to imagine space in a very basic way in an effort to conceptualize the relationship between experience and space more heuristically. I also wanted my participants to place themselves cognitively into a landscape they could produce from their mind’s eye. To that end I began with a “visualizing” activity where I instructed them to picture a landscape from their memory and sketch it on paper. I told them they could sketch important landmarks, wildlife, or other elements that were part of how they reimagined the space. Students reimagined childhood homes, summer places with loved ones, even military details in foreign locales. One student composed a sketch of her grandmother’s farm in rural Kentucky- the drawing was complete with a body of water, hills, vegetation, built structures and a mineshaft. This student remembered the mineshaft because it produced an extreme safety hazard, thus impeding movement. As she narrated how her family interacting on the land within her grandmother’s farm, she recalled the winding paths they took to avoid the mineshaft and admitted how she had forgotten that element of her childhood and was overcome with nostalgia as a result.

The exercise served as an effective tool to encourage students to see how meaning is embedded in space and from those meanings, we may distill narratives as well as new interrogations that broaden our understanding of how the past is informed by landscape. In the case of my student’s remembrance of the mineshaft she could as an adult learner begin a process of finding out why the mineshaft was there, when it was created, and the impacts that such resource extraction has on the state of Kentucky- all from her distilling the life narratives embedded in space.

Apart from students recognizing the meanings inherent in space and place it was important that they could connect spatial thinking to their disciplines. I asked everyone to state their areas of specialty. I was delighted at the wide spectrum of disciplines: Anthropology, History, Museum Studies, Modern Romance Languages, Literature, and more. Thankfully there are many spatial humanities projects available; I picked website projects that highlighted GIS functions within the humanities.

The first was “Mapping the Lakes: A literary GIS.” In this project two textual accounts of journeys made by Thomas Gray in 1769 and Samuel Taylor Coleridge in 1802 through the Lake District of northwest England were mapped. The site offers GIS representations of the two accounts and “suggests ways in which the mapping process opens up spatial thinking about geo-specific texts.”

Students were impressed with the potential of literary GIS and several students began thinking of possibilities with mapping works of literature and travel narratives.

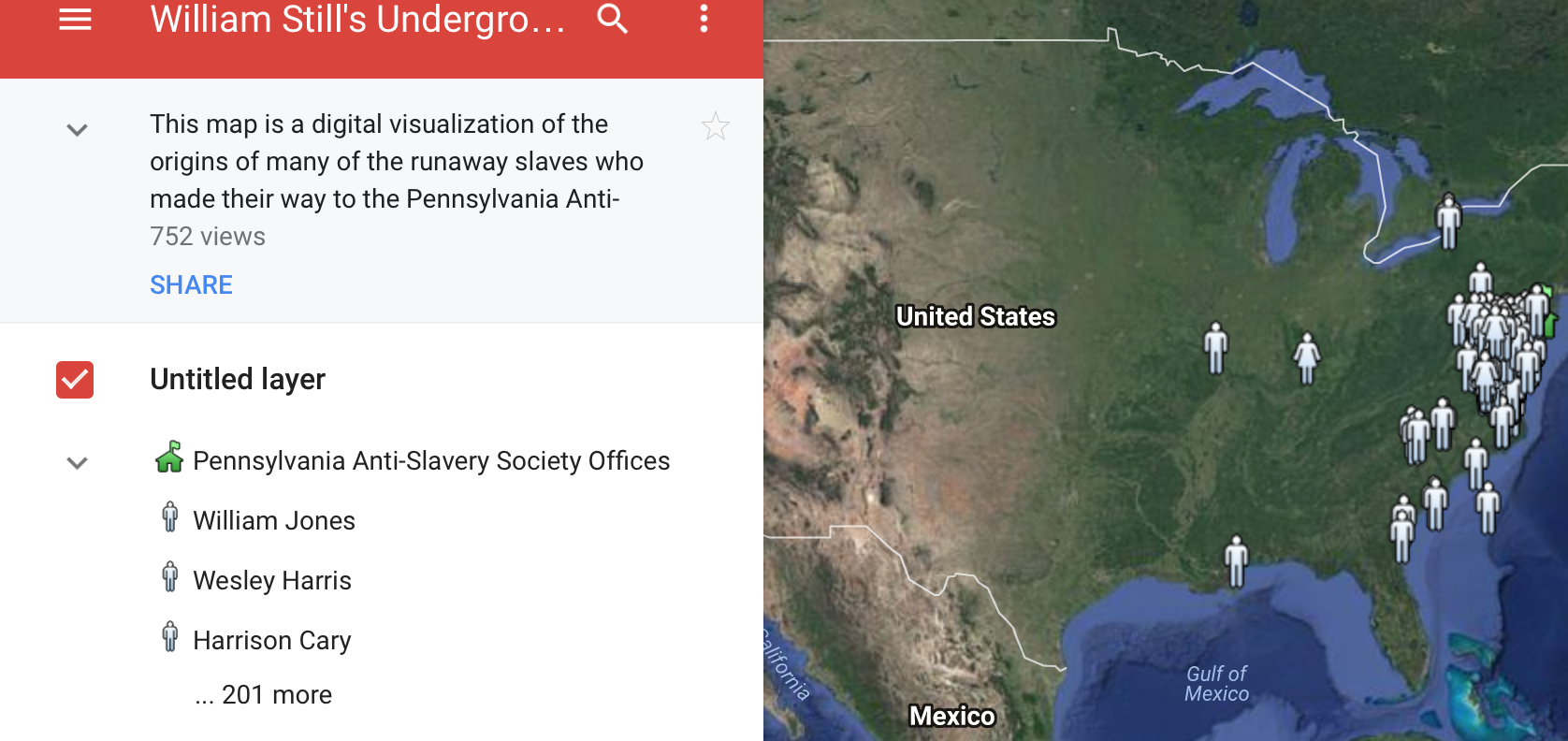

Another site I showed the students was Georgetown University Professor Adam Rothman’s William Still Underground Railroad Mapping Project. Rothman assigned students stories from William Still’s collection of runaway slave testimonies in order to analyze and discover spatially the origin of each runaway enslaved person’s journey for freedom. The students then plotted these points on a Google Map and annotated each marker with a summary of the enslaved person’s story, as well as a link to the primary source. An article on Dr. Rothman’s William Still project can be found here.

With Rothman’s project students saw places that were historically situated within geographies of slavery and from there could begin a closer inspection of slavery’s dominions as a result of the project’s visualization. From there I segued into the variety of tasks that can be performed within a GIS (visualization, spatial data analysis and management, etc) and listed several GIS interfaces commonly used (Googlemaps, CartoDB, ArcGIS).

It was wonderful facilitating the GIS session and like all student interactions I learned as much from them as they from me. Above all I was quite certain that students carried away with them a broader understanding of space as it relates to the human experience.