Men make their own history, but they do not make it as they please; they do not make it under self-selected circumstances, but under circumstances existing already, given and transmitted from the past. The tradition of all dead generations weighs like a nightmare on the brains of the living.—The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte, Karl Marx 1852.

If Economics is the dismal science, then History often feels like its close cousin, a kind of dismal humanities. The march through a year-long U.S. History survey can be at times overwhelming for students. The past is rife with examples of humans misbehaving. And despite best efforts to highlight more positive individual contributions alongside large-scale cultural, social, and political progress, the tide of the historical record is such that the optimism tank (particularly in the doldrums of a New England winter) sometimes feels all too close to empty. As students re-enter the winter trimester after an eighteen-day break, they’re charged with considering the early failures of Reconstruction and clearcut impact of industrialization in the latter half of the nineteenth century. This period, inherently wracked by the extreme contrasts of humanity’s potential, leaves them feeling uncertain about their own times. The connections to racial strife, class conflict, and technological change over this short period seem all too prevalent in their lives today. They feel, in a word, disoriented.

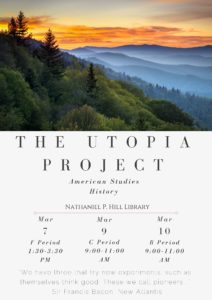

But in this disorientation there lays the potential for learning that extends beyond the traditional metrics of an achievement-conscious secondary school. Central to this discussion and our approach together is the concept of human agency, and just how much one person might do in the face of sometimes unyielding impersonal structures and forces that can make individual lives seem insignificant. Unsurprisingly this is a theme that resonates with teenagers tenuously close to entering adulthood. In years past I’ve asked students to craft a future utopia, utilizing the lessons learned from their study of the period and Progressive era sentiments so that they might avoid making similar mistakes to their historical ancestors. The project, a combination of historical inquiry, analytical and creative writing, and mixed media presentations, has proven successful for the most part. Students tend to identify key aspects that plagued society during the era and in doing so further articulate and define their utopian visions for the future. Admittedly, students sometimes struggle with the disassociation of time from a mostly knowable past to the uncertain and potentially infinite future. Further, they sometimes unknowingly wander into a vision for the future that in seeking to craft an ordered, equitable society unintentionally restricts or outright eliminates the human agency they intend to value and promote. Nevertheless, the assignment requires empathy for actors in their distinct, historical context and students gain insight into the importance of collaboration in the midst of diverse perspectives.

I’ve spent some time this winter break with Richard Evans’ Altered Pasts: Counterfactuals in History. The book, really a series of lectures given by Evans in 2013, examines the value (or lack thereof) of counterfactuals in history. Many, if not all of us, have wrestled with the merits of counterfactuals in some manner, whether in our classrooms or at a local pub, raucously, amongst our colleagues. The Utopia Project I’ve discussed above certainly dabbles in the counterfactual, although the aspect of the future and creating something entirely new skirts the “What if…” question inherent to the practice. After reading Evans however, particularly his discussion of French philosopher Charles Renouvier’s concept of Uchronie—that is, a “utopia of past time”—I’m of the mindset to embrace the counterfactual approach in much of what we do this winter, changing the Utopia Project to the Uchronie Project. In this instance, students won’t create something new in the future, but instead something new in the past. They’ll write history not as it was, but as it could, or even should have been. Doing so will eliminate the disassociation between the past and future, and it will require students to consider the impact of their decisions on the people living in that time. They won’t change the past, but they might just recognize the potential to shape their present and their future. The slate, it seems, can never be blank.