Surrounded by gifts, as many of us are this time of year, and looking forward to the next semester, I am trying to remind myself of the ways that my teaching is not a gift.

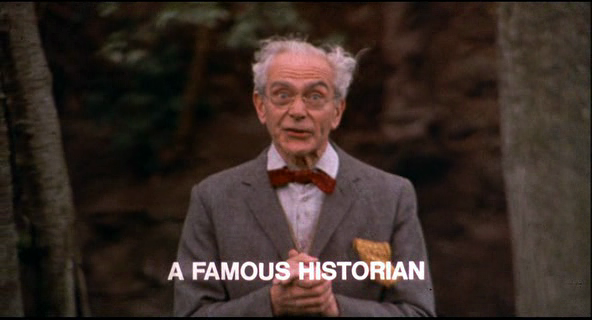

Anyone regularly reading this site already knows how dangerous it is to think of good teaching as a gift. Often those recognized as having a gift for teaching are those who embody charisma in particular ways that our culture recognizes. They hold the attention of an audience, they have a recognizable scholarly pedigree, or they look like a Google Images search for “historian,” and so are afforded some measure of respect, attention, and even deference before they open their mouths.

All those who teach history know that it isn’t a gift, including those who are seen as naturals at it by their colleagues and students. But at this time of year, when evaluations have rolled in and we’re thinking ahead to next semester, it can be tough to remember that.

Student expectations, informed by these broader cultural ideas of what a teacher should be, often conflict with what we try to do in the classroom. We explain what we’re doing, and why, but when that doesn’t work with some students – or worse, with an entire class – we fear that it’s not the methods, it’s us. We just don’t have the gift, and there’s no fixing that.

But teaching isn’t a gift, and good pedagogy – including confronting, absorbing, and managing student expectations – is a set of skills we accumulate, experiment with, and refine. This coming semester, as I teach a historical methods class for the first time, I’m going to try to remember that my struggles don’t mean I’m lacking some gift, they just mean I’m facing a new challenge in my craft.

Just as I try to remember that my teaching is a skill, not a gift, I must also remember that my teaching is labor, not a gift.

In this moment when historians are being called upon to “explain” what is going on in our country, and to do so by engaging with different publics, it’s important to remember we don’t have a gift we’re obligated to share with the world.

Whether we’re writing for a mainstream publication or for an academic journal, speaking to the members of a local historical society or the members of our MWF 9:30 AM class, we’re doing so because we have skills and expertise that we have spent time and money developing, skills and expertise that are valuable.

Historians being fairly compensated for the valuable work they do is a huge issue, and this isn’t the place to ponder dismantling the exploitative aspects of academic publishing, but I’m trying to remember that the work I do is valuable, and even if it’s important to society, it’s not something I am required to give without recognition or compensation.

I don’t mean this to say that we should not give of ourselves to our students, or that we should have no give when dealing with our students. But it’s important that we reckon with the intellectual and emotional labor we’re providing, or for some of us, the intellectual and emotional labor we’re expecting our colleagues to give disproportionately and without fair compensation and recognition.

Right now, my students are scared about a lot in the world, and I can help them by combining my intellectual skills and expertise with social and emotional awareness and skills. But I need to be more attentive in my teaching life to how much of this labor I’m doing, and the effect it’s having on me as a person. Simply because I can give it doesn’t mean that I have to, or that it’s even beneficial to, beyond a certain point.

I can make an intention to recognize this labor and protect my time and emotional health. But to put it bluntly, women and scholars of color are expected to give of themselves in this manner, uncompensated, and are penalized by colleagues and students alike when they do not.

So for this next semester, remember that you aren’t giving the world the magically-inborn gift of your teaching, you’re using skills that can always be sharpened. Remember too that you are laboring – emotionally and intellectually – and value that labor. Perhaps most importantly, remember that you should not demand others give of themselves in ways that you (or those above you in the academic hierarchy) are unwilling to recognize, value, and compensate.

Teaching isn’t a gift, and it could be a lot better if we all worked together to recognize that.