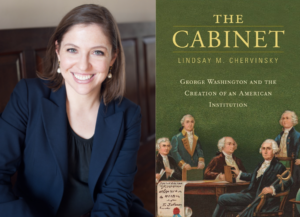

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Lindsay Chervinsky, Historian at the White House Historical Association. Dr. Chervinsky is discussing her new book The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution (Harvard 2020).

On November 26, 1791, President George Washington convened the first cabinet meeting in U.S. history—over two-and-a-half years into his administration. But the Constitution does not mention the cabinet and no additional legislation or amendment created the institution. So where did it come from?

On November 26, 1791, President George Washington convened the first cabinet meeting in U.S. history—over two-and-a-half years into his administration. But the Constitution does not mention the cabinet and no additional legislation or amendment created the institution. So where did it come from?

The Cabinet: George Washington and the Creation of an American Institution explores how Washington formed the cabinet only after he had experimented with and dismissed the advisory options outlined in the Constitution. He then relied on his military leadership experience as Commander-in-Chief of the Continental Army during the Revolution to guide his cabinet interactions. Washington modeled his cabinet meetings after councils of war, often using the same strategies to manage the sometimes troublesome personalities of his subordinates. Washington also used councils of war and cabinet meetings for the same purposes: to ask for advice, to build consensus for a policy, and to provide political cover for controversial decisions.

Washington’s cabinet established an important precedent for the executive branch and his successors. With the cabinet’s assistance, he carved out significant authority over domestic and diplomatic issues, issued the first veto, and asserted executive privilege. In his final years in office, Washington returned to primarily one-on-one consultations and written advice, which determined that future presidents would decide how they would interact with their department secretaries for themselves. Furthermore, each president selects their closest advisors—whether they be family members, vice presidents, cabinet secretaries, or others—and conducts those relationships with little public or congressional oversight. These relationships are Washington’s cabinet legacy.

Although the cabinet is a visible and powerful institution in the twenty-first century, the last book on its origins was published in 1912. Henry Barrett Learned examined the legislation that created each department but shared his findings before the emergence of the New Deal State, the military-industrial complex, or the modern imperial presidency. While there are countless books on the main characters, The Cabinet explains how the institution formed and their interactions within the cabinet shaped key moments in the Early Republic. People are always really surprised when I discuss the absence of existing literature, but it’s my hope that The Cabinet encourages readers, students, and historians to reconsider stories that must have already been told. Sometimes they haven’t, or haven’t been in a long time and could really use a refresher.

There are a couple of other key points I hope readers will take away from reading The Cabinet. First, the cabinet emerged organically and in response to pressures faced by the first officeholders. Its evolution demonstrates how much of the federal government was created after the ratification of the Constitution. Much of the state-building occurred as officials forged customs and norms in the daily process of governing. This point actually challenges many students’ (and frankly historians too!) misconceptions about the cabinet. Most people think it existed from day one of Washington’s presidency. The fact that the first cabinet meeting didn’t occur until two-and-a-half years into his presidency challenges this notion.

Second, the cabinet’s existence is itself a refutation of original intent. The delegates at the Constitutional Convention explicitly rejected proposals that would have created a cabinet and included other provisions for the president to obtain advice. Washington initially confined his actions to those options, before rejecting them as insufficient. I’ve used readily-available primary source material to share this argument in classrooms. I have students evaluate the options outlined in Article II, Section 2 of the Constitution while reading select passages from notes during the Constitutional Convention. I have them consider the council proposed by Charles Cotesworth Pinckney on May 29, 1787 and an anonymous article published by “Americanus II” on December 19, 1787. All of these documents are available in the Documentary History of the Ratification of the Constitution. Taken together, these documents reveal the delegates’ expectations for the president’s advisors—and how far Washington strayed from those expectations.

Third, as historians, we tend to segment history into periods: The Revolutionary War, the Confederation, the Early Republic. The Cabinet demonstrates how much the war experience informed politicians’ actions once they were in office. For example, we all know Jefferson and Hamilton hated each other, right? But their unique backgrounds help explain the conflict. Hamilton spent his war years fighting in dirty, smelly conditions. He constantly faced shortages of food and supplies and slept in less-than-comfortable locations. He also debated and schemed with other officers in raucous councils of war. He didn’t avoid confrontation, he thrived on it. Jefferson, on the other hand, spent the first few years of the war as governor of Virginia, before serving several years abroad as a diplomat. Diplomacy typically occurred in elite homes, surrounded by comfortable furniture, with servants or enslaved individuals on hand to smooth conversation with fine wine or delicious food. If voices were raised, Jefferson was likely doing something wrong. It’s no surprise Jefferson found the contentious cabinet meetings in Washington’s cramped, hot, uncomfortable private study an unpleasant experience.

Finally, while The Cabinet is political history, it relies on material culture, gender, and cultural norms. I couldn’t describe the cabinet interactions without knowing what the space looked like or how the meeting room might have shaped their moods. Furthermore, Hamilton and Jefferson’s competing presentations of masculinity, one based on military bravery and the other on cultured worldliness, influenced their political perspectives. I hope other historians will be inspired to blur the lines between political and material cultural histories and consider how their work might benefit from incorporating both approaches.

I would love it if The Cabinet contributed to a number of college courses. It follows the narrative arc of Washington’s service during the war, the Confederation, and the presidency, and it covers many of the key moments in the 1790s: the Neutrality Crisis, the Whiskey Rebellion, the debates of Jay’s treaty, and more. Accordingly, it could serve nicely as the text for the Confederation and Early Republic period in a survey course. Classes on the American Revolution or the Early Republic would be a natural fit as well. The Cabinet would be valuable for courses on the presidency to explore how the executive branch began and what precedents Washington established that guided his successors. Finally, while I didn’t set out to write The Cabinet as a story about leadership, the book speaks to the field and examines Washington’s leadership strategies.

Chapters one through three examine the war and Confederation period and would be more helpful for the 1770s and 1780s. Chapters four and five explore the early days of the cabinet and how the participants struggled with comparisons to the British cabinet. These chapters would speak to the organic nature of state-building in the Early Republic. Chapters six through eight analyze the Neutrality Crisis, Whiskey Rebellion, and Jay Treaty, respectively. While they build on each other, these chapters can be used individually as needed to provide case studies for each critical moment.

I hope this overview is helpful and I’d like to make the same offer I posted online. If you decide to use The Cabinet in your course, I would be happy to Zoom into the class if that would be helpful or interesting for your students.