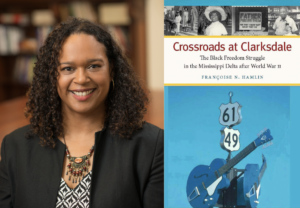

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Françoise N. Hamlin, Associate Professor in History and Africana Studies at Brown University. Dr. Hamlin is discussing her book Crossroads at Clarksdale: The Black Freedom Struggle in the Mississippi Delta After World War II (North Carolina 2012). This excellent book has won the 2012 Berkshire Conference of Women Historians Book Prize and the 2013 Lillian Smith Book Award.

Crossroads at Clarksdale is not about the Blues. This book tells another story about African American lives in Clarksdale and the Mississippi Delta, lives that occurred alongside the rich cultural production happening in music for which the area is renown. Crossroads is about how people get things done when the odds are stacked against them. Located in one place, I show how black folk move in and out of Coahoma County, what they bring and what they take away, and what is left after the reporters and headline-making visitors leave. I start in 1951 when the local people established a branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in response to a rape case where a white man assaulted two black women. Through the chapters I plot the mass and individual protests to desegregate public spaces and the schools, and to establish the antipoverty agency hailed by the federal government as a flagship rural demonstration project.

There are many benefits from local studies — it illustrates how the broad umbrella of what we commonly label the Civil Rights Movement is actually a mass of movements – and that even within locales activists executed many campaigns, sometimes simultaneously. Using oral histories, personal and organizational papers, city and court and school board records and minutes and state records, I pieced together a quilt of narratives that provides a sense of Clarksdale from a different point of view. Focusing on African American experiences, I produce knowledge that develops what we know about how black folk define themselves and made sense of their lives, while shaping and navigating the societies and cultures they build and inhabit.

Crossroads has three major intertwining themes. My numerous interviews document unique stories, building the chronology of activism and struggle, but I pulled out and highlighted two of the leaders, Doc Aaron Henry and Mrs. Vera Pigee and told their stories, complicating leadership styles and techniques. In Clarksdale formal male leadership came through Henry; and Pigee was an activist mother (self-defined). Their experiences and interactions mirror gendered leadership dynamics that define the era and that generation. This study also complicates the idea of group membership –what I called flexible alliances/loyalties. Analyzing how different organizations at all levels (local, state, and national) worked and wrestled with each other in one place, I demonstrate how local people manipulate those dynamics in order to further local goals. For example, pharmacist Aaron Henry, who helped kickstart the local mass movement in the fifties, did not hesitate to join multiple organizations and pull resources from each into the local movement; whereas Medgar Evers, as NAACP field secretary, could not maintain multiple memberships without angering his employer. The reality of how local movements function shatters what I call the “kumbya” image that insinuates all black folk arm in arm singing hymns and in agreement. In this way, I model how local histories can yield questions and methods with which to study other places, and how all the stories (a mass of movements) patchwork into a national story.

Lastly, I complicate success by ending the book with President Bill Clinton’s 1999 New Markets Tour of the five most economically depressed areas in the U.S. where Clarksdale was one, and plotting how school desegregation efforts met obstacles. Yet I had just told multiple stories of decades-long gallant movement activity and organizing. National memory of the mass of movements lean into narratives of triumph, equality, and an end to Jim Crow, but I challenge readers to think about where we are now in relation to where we were then. How do we assess success when poverty rates are still too high, when the schools are still underfunded and practically re-segregated, and there are not enough industries to keep residents employed with living wages, which has resulted in a regional brain drain? As I tell my students, knowing your history, helps you to move forward with purpose. Crossroads initiates so many conversations and debates about history, Mississippi, social movements, race, gender, class, self-definition, equality, progress, and success.

I wrote this book for the people about whom I write so it is accessible to general readers and complex enough for professional historians. It can be taught as a book about methodology – how to excavate stories through oral histories, extensive archival work, and the ethics of storytelling. It also reads well in U.S. history survey courses as it encompasses social movements, race, gender, and class with enough flexibility for teachers to dive into any topic listed above. For more specialized courses in African American history/studies – this book adds to the rich historiography about twentieth century Mississippi, African American history, the Black Freedom Struggle, race/racism, and gender studies.

The book is a story, written as a narrative, so the character development threads through the chapters. Chapter two, however, sets up Mississippi and Vera Pigee (and it is one of my favorite chapters). It also includes my close readings of two photographs that help students see how using different primary sources enables historians to piece together what happened and how people did their work when not enough written evidence exists. It provides a good template for teachers to perhaps guide students to analyze and “read” other photographs (in the book or elsewhere) and build a research toolkit using the content to reveal the process. Indeed, in my own courses I include several photographs and alternative sources like oral histories (widely available online) to train students to find knowledge beyond traditional archival material – a vital skill for finding voices not usually included in the archives.

The next step in skill-building becomes teaching students to discern their sources. In Crossroads I layer sources to triangulate the information in order to get as close as I can to the “truth.” Oral histories come with complications, and aging memories are just the start. Thinking about oral histories as primary and secondary sources force researchers to dig further, to corroborate what people say or to ascertain why people might choose to “selectively remember” events or people. Again, teaching our students to be critical thinkers begins with peeling back narratives and taking a microscope to the sources. I do not hide the process in Crossroads as I want my method to be transparent which then insulates the narrative from particular critiques and invites conversations.

With my attention to sources and skill-building, Crossroads disabuses any notion that the civil rights movement hinged on luminous national figures like Martin Luther King, Jr., or Roy Wilkins. Drilling down to find the granular detail in local stories yields broad questions, themes, and insights that enable a better understanding of the whole. In this way, readers need not be invested in Clarksdale per se to find value in this book as a narrative and as a methodological template. For those who assign the book for classes, I am wholly invested in why history matters to answer student questions so feel free to contact me!