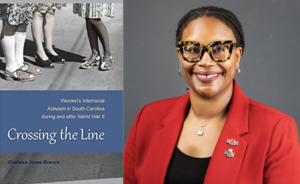

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Cherisse Jones-Branch, Dean of the Graduate School & James and Wanda Lee Vaughn Endowed Professor of History at Arkansas State University. Dr. Jones-Branch is discussing her book Crossing the Line: Women’s Interracial Activism in South Carolina during and after World War II (Florida 2014).

Crossing the Line: Women’s Interracial Activism in South Carolina during and after World War II, explores how African American and white women in all-female and mixed-gender organizations interpreted and dealt with racial issues and how individual women worked together against racial injustice in South Carolina during and after World War II. It also examines the accomplishments and limitations of interracial activism as black and white women pursued sometimes similar, but occasionally conflicting agendas. Although black and white women sometimes found it difficult to overcome their fear and distrust of each other to pursue activism across racial lines, they realized that doing so gave them the best opportunity to enact change. They therefore took careful but courageous steps as they embarked upon their journey to improve race relations and conditions for African Americans in South Carolina.

Crossing the Line: Women’s Interracial Activism in South Carolina during and after World War II, explores how African American and white women in all-female and mixed-gender organizations interpreted and dealt with racial issues and how individual women worked together against racial injustice in South Carolina during and after World War II. It also examines the accomplishments and limitations of interracial activism as black and white women pursued sometimes similar, but occasionally conflicting agendas. Although black and white women sometimes found it difficult to overcome their fear and distrust of each other to pursue activism across racial lines, they realized that doing so gave them the best opportunity to enact change. They therefore took careful but courageous steps as they embarked upon their journey to improve race relations and conditions for African Americans in South Carolina.

Examining the tumultuous years during and after World War II, Crossing the Line unearths black and white women who were the unsung heroes of the South Carolina civil rights movement and centers their interpretations of and reactions to the local and national events swirling around them. Black and white women’s efforts to cross South Carolina’s racial divide helped lay the groundwork for the broader civil rights movement in the 1960s and 1970s. This book contributions to the little known story of women’s activism during the civil rights movement. It further challenges the notion that the South was monolithic in its reactions to the civil rights movement. Despite the increase in scholarship on racial activism, South Carolina has not been examined to the same extent as North Carolina, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. And even less work has focused on black and white women. Most of the women discussed in Crossing the Line had long histories as activists that in some cases dated back to the World War I years through such organizations as the Commission on Interracial Cooperation. Their activism was also influenced by their membership in the Young Women’s Christian Association, local affiliates of the National Association of Colored Women, the NAACP, and such interdenominational Christian organizations as Church Women United, all of which supported racial and social activism. Crossing the Line also upends the notion that women were confined to the domestic sphere before and particularly after World War II. Despite the emphasis on domesticity after the war, many women refused to acquiesce to such demands. Their activism was additionally informed by maternalism. Black and white women were able to defend their public social and political involvement because they understood that they were ultimately shaping a better world for their children and grandchildren.

In my estimation, Women’s, African American, and Civil Rights history courses would significantly benefit from Crossing the Line. Chapter one, “The Lord Requires Justice of Us:” Civil Rights Activism in World War II South Carolina,” and chapter five, “Become Active in This Service to the Community”: The Possibilities and Limitations of Racial Change and Interracial Activism in South Carolina,” are the most useful because they lay the foundation for a thorough understanding of how black and white women were influenced by the democratic rhetoric of the World War II years to push for racial equality. Despite their very different backgrounds and racial views they were compelled to enact change because they wanted to realize a more fair and equitable world for everyone. Accordingly, they mobilized around such issues as political access and participation, education, and racial violence. They were painfully aware of work required to undo the damage caused by deeply entrenched racism and Jim Crow laws. Some black and white women struggled to conquer the mutual distrust that existed between them, because they understood that it hindered their effectiveness as activists. Other women however, formed friendships as a result of their work in shared racial and social reform organizations. Such relationships were possible because these women had attended college, an experience that exposed some of them to diverse women as members of racially inclusive organizations, and prepared them for a lifetime of activism. Chapter five considers how white and black women’s organizations increased or in some cases decreased their activism, particularly after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court decision. Black women, however, continued to focus obtaining and fully exercising the right to vote and to access equal educational opportunities as white women turned their attention to less controversial racial activism like combatting South Carolina’s pervasive poverty.

To produce Crossing the Line, I excavated numerous personal and archival collections from repositories located in South Carolina, North Carolina, and Massachusetts. In particular, I utilized the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, because some of the women I wrote about were interviewed before their deaths. These interviews are available online and are freely accessible to the public. I also mined many state, local, and national newspapers to track black and white women’s activism in South Carolina. Many of these newspapers are digitized and available through such university library databases as African American Newspapers and Historical Newspapers. They can be easily incorporated into classroom discussions and are further excellent examples of women’s wide reaching influence as change agents.

In the final analysis, South Carolina women labored to combat racial injustice in the state and were directly informed by the World War II years, during and after which it was patently clear that change was inevitable. Although they encountered obstacles at every turn, they enlightened themselves and others about the state’s racial problems and sought and at times succeeded at reaching across the racial divide to implement long lasting and meaningful change for all in the Palmetto State.