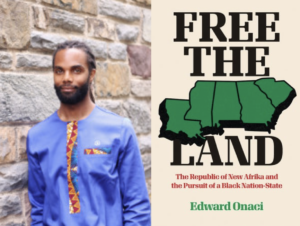

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Edward Onaci, Associate Professor of History at Ursinus College. Dr. Onaci is discussing his new book Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State (UNC 2020).

Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State is the first full history of the New Afrikan Independence Movement. It explores why and how people began pursuing the creation of the Republic of New Afrika, how the central ideas and goals of the movement compared and contrasted with those of other efforts during Black Power era and beyond, and how New Afrikans, the people who since 1968 have worked within this movement, tried to live according to the movement’s ideas. I argue very simply that people live according to the political ideas and ideals they espouse; but as they attempt to live in this manner, they continually rethink and reshape the movement.

Free the Land: The Republic of New Afrika and the Pursuit of a Black Nation-State is the first full history of the New Afrikan Independence Movement. It explores why and how people began pursuing the creation of the Republic of New Afrika, how the central ideas and goals of the movement compared and contrasted with those of other efforts during Black Power era and beyond, and how New Afrikans, the people who since 1968 have worked within this movement, tried to live according to the movement’s ideas. I argue very simply that people live according to the political ideas and ideals they espouse; but as they attempt to live in this manner, they continually rethink and reshape the movement.

The book encourages instructors to recognize an overlooked dimension of U.S. history by highlighting an ongoing movement of African-descended people who have sought self-determination and self-government as viable solutions to America’s problems of racism and imperialism. Their approach to seeking liberation necessarily exposes racial capitalism, slavery, and ongoing oppression of Black and other historically oppressed peoples as foundational to the U.S. nation-state. In other words, these characteristics are not unfortunate deviations from the country’s highest ideals, nor are they problems that the country will eventually solve without major fundamental changes.

Because New Afrikans have sought independence, not full U.S. citizenship, survey courses may use Free the Land to teach about a group of people whose aims and principles reflect ideas that are typically overlooked in the teaching of U.S. history. It also may serve as a starting point to explore closely related topics that are mentioned in the book, but for which Free the Land offers no sustained analysis. These include the U.S. state’s relationship to Puerto Rico and various indigenous nations, as well as U.S. foreign policy in Central and South America, its economic and military interests on the continent of Africa, and more. Beside U.S. and African American history surveys, I recommend that courses focusing on African Americans and the African Diaspora consider using Free the Land in part or in its entirety. These include: courses about social movements, either U.S.-based or global and comparative; courses focusing on the Civil Rights and Black Power movements; courses exploring Black and/or U.S. political thought; and courses exposing students to Black radicalism in the United States, Africa and its diaspora, and the broader trends of anti-imperialism that arose during the mid-twentieth century.

Free the Land is written so that some chapters may stand alone, which is especially useful for courses that do not have space for a full scholarly monograph. For instructors seeking general information about the New Afrikan Independence Movement, chapters one and two offer a historical overview and analysis of the movement’s political ideology. Chapters three and four are most useful for those who are interested in the lived experience and culture of activism. If one is teaching about state repression, chapter five focuses on how New Afrikans experienced and learned from COINTELPRO and violent interactions with police. Chapter six focuses on the development of more recent New Afrikan Independence Movement organizing, including New Afrikans’ contributions to the ongoing struggle for reparations. Taken in part and as a whole, this book brings new insights to students of African American, United States, and African Diaspora histories.

Pursuing this research has helped me hone in on ideas and interpretations of history that bring a fresh perspective to my students. I am much more attentive to notions of self-sufficiency, if not total self-determination, and how thinkers and actors who have put forth such ideas negotiated their political beliefs with the realities of living in the United States. Issues of space and place, especially as they regard control over land, now get more attention within various courses that I teach. Finally, my survey courses more explicitly permit discussions about the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and U.S. powerbrokers’ and activists’ changing interpretations of it over time, in addition to rethinking the multiple potential meanings of justice and reparation for African-descended people.

Researching about the New Afrikan Independence Movement has also exposed me to internet archives that students may find useful in their studies and research. For example, I used the Mississippi Department of Archives & History’s “Sovereignty Commission Online” during the research for my book. It is available here: http://da.mdah.ms.gov/sovcom/. I used this resource to better understand how Mississippians who viewed the presence of New Afrikans and their work as threatening reacted to and spread ideas about the New Afrikan Independence Movement. In the classroom, this resource may aid in the analysis of activism and surveillance of activists in the state of Mississippi. I would also encourage instructors to think about information literacy and what we can teach students about identifying trustworthy internet sources when conducting research.

In writing Free the Land I wanted to champion interdisciplinarity, which is critical to my methodology. Although a historian, I find it useful to utilize ideas popular within sociology, political science, political theory, geography, and cultural theory inasmuch as I am able. While I take seriously what archived documents offer, my use of theoretical concepts and approaches from other disciplines is readily apparent to many readers. For example, when I explore “lifestyle politics,” the central concept of the book, the stories and analysis that I provide are informed by the segment of social movement theory that is concerned with the “biographical consequences” of activism. I also engage with name studies, itself an interdisciplinary field. I hope that students learn the value of reading widely and picking up any conceptual or theoretical tools that they find useful in their own work, as no one discipline is fully equipped to help us interrogate the phenomena interest us.

When thinking about the potential outcomes of assigning this text in the undergraduate classroom, I hope that instructors encourage their students to be open to an important challenge of New Afrikan Independence Movement history. We are taught that African and African-descended people’s political objectives throughout U.S. history have related solely to becoming full citizens and fixing a “broken” system of governance. My research demonstrates that at least some Black people have consistently advocated for independence, self-government, and financial repair. Instead of seeing these ideals as uniquely radical or politically impractical, my book frames them as both a natural desire of humans and a logical outcome of an oppressed people’s careful analysis of their predominant conditions. Sometimes it is hard to accept that not everyone wants to exist as victims of the U.S. state and its people, typically because we have been taught to agree with the myth of American exceptionalism. The history that I present attempts to disabuse us all of any uncritical acceptance of that myth.