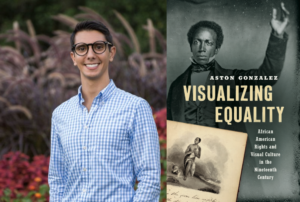

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Aston Gonzalez, Associate Professor of History at Salisbury University. Dr. Gonzalez is discussing his book Visualizing Equality: African American Rights and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century (UNC 2020).

The fight for black rights in the nineteenth century not only took place at marches, political conventions, church gatherings, and courthouses; the fight included print and visual culture created and circulated throughout the United States by African Americans. Visualizing Equality: African American Rights and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century traces how African Americans marshaled numerous visual technologies to advance campaigns for black rights in the United States between 1830 and 1880. These black intellectuals, including formerly enslaved people, countered common racial stereotypes and produced images that celebrated the need for black voting rights, freedom from slavery, and full claims to citizenship. These artists’ networks of transatlantic antislavery patronage, travels to Europe, Liberia, and Haiti, as well as their commentaries on black emigration, reveal their expansive and evolving political engagement. The book moves chronologically as it centers their experiences.

The fight for black rights in the nineteenth century not only took place at marches, political conventions, church gatherings, and courthouses; the fight included print and visual culture created and circulated throughout the United States by African Americans. Visualizing Equality: African American Rights and Visual Culture in the Nineteenth Century traces how African Americans marshaled numerous visual technologies to advance campaigns for black rights in the United States between 1830 and 1880. These black intellectuals, including formerly enslaved people, countered common racial stereotypes and produced images that celebrated the need for black voting rights, freedom from slavery, and full claims to citizenship. These artists’ networks of transatlantic antislavery patronage, travels to Europe, Liberia, and Haiti, as well as their commentaries on black emigration, reveal their expansive and evolving political engagement. The book moves chronologically as it centers their experiences.

Many scholars have studied white Americans’ visual depictions of blackness during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries to explore national debates about African American rights. Others have demonstrated that studying race, images, and blackface minstrelsy together reveals the profound ways that images and performances altered how Americans envisioned themselves as people of different races and ethnicities. More recently, many others have examined how images displayed and disseminated nineteenth-century debates concerning African American freedoms.

Visualizing Equality, however, focuses on the images that African Americans themselves created. This African American cultural production reveals how black activists adopted – and were central to adopting – additional strategies to secure social and political rights for black Americans. In conversation with the scholarship in African American cultural history, visual culture, and political activism, this book demonstrates how African American cultural producers seized nineteenth-century technological innovations to harness the persuasive power of visual material. In doing so, they crafted inclusive conceptions of race and citizenship before, during, and after the Civil War.

Visualizing Equality, like many studies of marginalized people, grapples with limited sources to reconstruct the lives and decisions made by them. There are times when precise information about the past cannot be known given the limited number of extant primary documents, but there are ways that I worked to provide a portrayal that was both vivid and accurate. For example, Robert Douglass Jr. was an African American activist in Philadelphia who worked as an engraver, painter, and photographer who traveled to Haiti and painted numerous scenes there. I have not been able to find any of these paintings, but a few newspaper advertisements describe the subjects of these paintings with a very brief description as well as how Douglass used them to facilitate discussions about that black republic when he returned to the United States. Reading these surviving related materials closely allows a much fuller picture of these paintings and how Douglass used them. This example could be used to teach students to not give up when researching and should instead look for other sources to help triangulate the actions or motivations of historical actors. Instructors can use Visualizing Equality to examine how historians must get creative methodologically while still being accurate when the “perfect” primary document that would provide historical clarity proves elusive.

Though the topical and chronological spread of the book makes it a good fit for both halves of the U.S. History and African American History surveys, I think the book would prove especially valuable for instructors wanting to highlight the connections between cultural and political histories. Classes that feature sections on African American politics, free black communities, and the Black Atlantic would find this book very useful. Instructors of cultural and visual studies courses could use any portion of the book because I write extensively about how people produced, collected, distributed, reacted to, and made meaning from images. Chapters 1 and 2 center on free black activists in Philadelphia and New York City and include lots of visual material that students can use to discuss the antislavery movement. Chapter 4 on Black activists’ moving panoramas in the United States and Britain is about a fascinating visual media form that most students do not know well. Chapter 6 can be used to teach the visual landscape of the Civil War and the stakes of depicting African Americans. Well before the coronavirus pandemic, but certainly now in the midst of it, a number of archives made many of the images in the book publicly accessible. The websites of the Library of Congress, the Library Company of Philadelphia, the American Antiquarian Society, the New York Public Library, and the Massachusetts Historical Society make many of the images in Visualizing Equality freely available to the public. Several of the pamphlets, books, treatises, and other printed works that provided the foundations for this book can also be found on the Internet Archive website.

In my experience teaching undergraduate and graduate students, images have proven to be accessible entry points to broader conversations about historical events, people, and processes. Sometimes images appear deceptively easy to understand; it is only by adding historical context and explaining how different elements of the image work together to convey ideas about the past that students realize how complex images can be. I teach using many types of images and prompt students to extract historical truths from them in both lectures and seminars. This method of teaching enlivens the histories of the people and events we study and rewards students for identifying the connections between the images and required readings. Teaching with them helps history come alive. For example, asking students how different elements of a portrait – clothing, posture, eye contact, composition, and background information – suggest ideas about the sitter is important, but so too is connecting these pictured characteristics to broader course themes of commerce, gender, class, education, and many others. Asking students to describe what they see and then make sense of it prompts students to marshal evidence, piece by piece, and construct an argument about an image and its attendant histories.

Another way to help students understand the power of images is to ask them about the images and videos in their lives today. Social media platforms are one major source of their image consumption. They will likely describe how images of all sorts influence their fashion choices, their social media presence, their favorite musical artists, and their opinions on our nation’s political landscape. Drawing parallels between the use of images in the nineteenth century in the service of social transformation and the ways that people use contemporary media forms to document discrimination and violence while demanding dramatic reforms will help students understand the long history of images as a vehicle of political ideas.