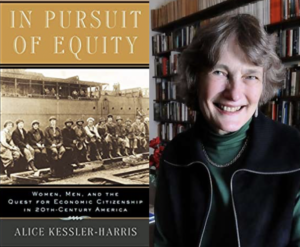

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from Alice Kessler-Harris, R. Gordon Hoxie Professor Emerita of American History and Professor Emerita in the Institute for Research on Women and Gender at Columbia University. Dr.Kessler-Harris is discussing her Bancroft prize-winning book In Pursuit of Equity: Women, Men, and the Quest for Economic Citizenship in Twentieth-Century America (Oxford 2001).

We think of political freedom as the key to human emancipation and an essential element of full citizenship. This book argues that economic freedom—or economic citizenship—is equally important, and especially for women. The book explores the history of women’s efforts to achieve justice, or equity, in the long twentieth century. It delves beyond equal wages and equal opportunity to reveal how a culture embedded in conventional gender norms has privileged some men and deprived women of many prerogatives of citizenship. And it traces how formal and informal constraints on economic access have shaped the perquisites of citizenship. While its focus is on women, the implications of the material extend to racial and ethnic groups of all kinds.

Historians of Native Americans and of African Americans have successfully examined concepts like liberty, equality, and democracy to demonstrate the nation’s failure to achieve its declared hopes. These words have framed the broad narrative of national history, and yet their implications have rarely been examined for women. As this book shows, when we examine each of these ideas with relationship to women, we discover how far expectations of democratic participation have fallen short.

Historians of Native Americans and of African Americans have successfully examined concepts like liberty, equality, and democracy to demonstrate the nation’s failure to achieve its declared hopes. These words have framed the broad narrative of national history, and yet their implications have rarely been examined for women. As this book shows, when we examine each of these ideas with relationship to women, we discover how far expectations of democratic participation have fallen short.

In Pursuit of Equity opens in the early years of the twentieth century, in a fully formed industrial society, when battles for women’s suffrage and for decent working conditions pervaded public conversation. It probes the effects of industrialization on women’s opportunities in the labor force and investigates how racial and class distinctions expanded and constrained workforce opportunities. It traces legislative and judicial interventions into women’s increasing efforts to stretch the meaning of the family and asks how these sharpened racial divisions across the board. And it illuminates changes in masculine identity as assembly lines replaced satisfying work for more and more males while sisters, then daughters, wives, and mothers took on the responsibility of paid work. At every step, In Pursuit of Equity, queries the intersection between these changes in work and family on the one hand, and political responses on the other

Moving through the twentieth century, successive chapters explore how men and women coped with economic depression, repeated wars and the challenges of a consumer society. It focuses on the shifting gendered pressures and responses and on the political reactions of people from different class strata as some women assumed greater roles while others fell further from achieving the freedom and the capacity to participate that they sought. And it concludes with questions. By the end of the twentieth century, we note, women have moved closer to equality with men in their class and racial cohorts. And yet, we also note the social diminution of equality overall. For some men and women, equality has meant greater autonomy, the capacity to create new family forms, and the benefits of a consumer society. But others have paid a steep price in the form of continuing poverty, a diminution of the quality of life, and a stiff limits on their capacity to exercise democratic voice. The story is uneven at best, but it reflects the challenges posed by a society in which changing gender norms have shaped the circumstances of everyday life.

In asking questions about whether women (single and married) have historically experienced liberty or equality, or democracy in the same way as the men of their race and class, the book illuminates how different groups have experienced the U.S. in different ways. It also exposes the hidden barriers that discourage the achievement of noble goals. More specifically, it raises questions about the influence of a gender system that for most of American history placed women into a separate legal category, diminished their social agency, and denied them many of the benefits of citizenship.

Students who read this book will be encouraged to ask questions about how culture and tradition can blind even well-intentioned people to the well-being of others. Students will learn about how the deeply intertwined tenets of race, class, and gender shape the expectations of individuals and frame their understandings of fairness. They will begin to understand something of the relationship between equality and democracy on the one hand and the tension between them on the other. They will learn something of how a society that valued individualism and promoted the male breadwinner family could no longer sustain its family-derived values when it required women to become breadwinners as well. And they will be led to ask how a prevailing value system (such as individualism or liberty might be tested against powerful values of community and cooperation.

Teachers might use this book in many different ways. Those who teach the survey course will find it a useful lesson in how one group of people used legal strategies, political influence, and personal ambition to alter the trajectory of the nation. They will encourage students to think about the effect of social movements in re-shaping law and society. Teachers of law and legal history will want to investigate the many challenges to the courts posed by women who insisted on inclusion; teachers of economic and social history will see in the fight for access to education and jobs a demand for Intellectual historians will interpret women’s demands for full citizenship in the light of the positive freedoms that Isaiah Berlin advocated for full participation. They will raise questions of inclusion and exclusion as well as of whether dropping barriers to exclusion is enough to ensure inclusion for any group. In short, the book provides a rich array of materials from which to debate what counts as freedom, and what is required for a healthy democracy. Women’s Studies teachers will be able to use the material to push their students into seeing how gender has mattered in the past and asking whether gender still matters.

Many chapters in the book lead to elements of inquiry into the meaning of gender, but two provide perhaps the most readily accessible. Chapter 2 speaks to the pressure for unemployment insurance in the twenties, and then its passage in the 1935 Economic Security Act. It raises questions of who counts as a “worker” in this period, and how entrenched notions of masculinity found their way into every state and federal iteration of social insurance. Chapter 3 focuses on the passage and amendment of Title II of the Economic Security Act. This is the title that created the contributory old-age pensions that we now call Social Security. The chapter reveals how the legislation evolved around a desire to help male-bread winners live a dignified old age. The 1939 amendments that extended these benefits to the wives, surviving widows and children of deserving men provide a particularly revealing portrait of how fully such legislation incorporated gendered norms. These chapters are largely based on the committee hearings that produced legislation. This material is readily available in the National Archives and online, and it provides students with revealing illustrations of the kinds of conversations that go into making our laws. Here students can see legislators making explicit distinctions of class and race as well as gender. They are asked to enter into the imagination of influential individuals who have shaped the nation’s history.