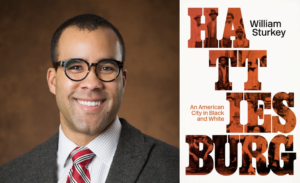

Teaching United States History is excited to present Teach My Book, a series of posts where distinguished authors reflect on their work and how instructors might integrate their insights into the classroom. Our thoughts today come from William Sturkey, associate professor of history at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Dr. Sturkey is discussing his book Hattiesburg: An American City in Black and White (Harvard 2019).

July 2, 1964, was an amazing day in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. That day was the first day of Freedom School, and hundreds of Black youths poured into the city’s old Black churches where they began to learn more about the Civil Rights Movement and African American History. The kids were bursting with energy. They arrived at the churches singing and clapping, their bodies pulsating with possibilities and their minds set on freedom. So many students came out that the churches became too crowded, forcing the Freedom School organizers to close registration. But the kids wouldn’t hear of it. They began unlocking the basement windows and distracting the teachers so that their friends could sneak into Freedom School. Along with the kids, one of the people who came that day was an 82 year-old man. He told an interviewer that he was there to “learn more in order to register to vote.”

My book Hattiesburg started as a study of those kids. I wanted to follow their lives and learn of their activities in the years after they attended Freedom School. But the book took a turn when I sat down to begin Chapter One. I thought Chapter One was going to be about the origins of those Black churches. I wanted to try to explain how it was that those Black churches became such powerful sites in the Civil Rights Movement. I wanted to explore the history of those churches in that community. And I wanted to know who had laid the foundations of those incredible places. Ultimately, it was the search for these answers that led to the book Hattiesburg: An American City in Black and White.

Hattiesburg is an epic, biracial history of Jim Crow in a Southern town. It opens with the founding of the town in the middle of the Mississippi Piney Woods in the 1880s and uses the lives of selected individuals to take readers through an intimate portrait of life in the Jim Crow South. It places Hattiesburg and its people in the carriage cars of American modernity, showing how the local Black and white communities responded to major changes in American life between the end of Reconstruction and the Civil Rights Movement. The chapters are racially segregated. They oscillate between black and white perspectives, showing the communities as they were in real life; separate but intractably locked. The end result is a fresh look at the history of Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement.

Hattiesburg shows that Jim Crow was never static. Rather, the view from one place shows us how race and economic changes altered Jim Crow within itself. Three primary factors created these patterns of change across time. The first was the reliance of the Southern economy on external resources. A deep dependence on federal and Northern investment often undermined the ability of local white supremacists to maintain their system of racial apartheid. The second factor was the mobility brought by economic change. Black Southerners found ways to move within and even beyond the Jim Crow South. And those who stayed leveraged those movements for improved resources, especially schools. The Black high school in Hattiesburg was a product of the Great Migration of African Americans away from Mississippi. The third and final factor was segregation itself, which necessitated that Black people develop their own institutions and community organization traditions. These institutions later launched the very movement that destroyed Jim Crow. Through a luminous narrative featuring a fascinating slew of characters, Hattiesburg takes us beyond the idea of a “movement,” however long or short, to offer a fresh, innovative view of Jim Crow in a place across time.

Hattiesburg could be used in any course about modern United States History, Southern History, or African American History. It alters some of the dominant narratives in several different ways. First, despite the onset of Jim Crow, the “nadir” period of Black history was actually a profoundly important and productive era for many Black communities, whose institutional foundations were established during the rise of the New South. If you look at the churches made famous during the Civil Rights Movement, you can trace almost all of their institutional origins to the very same era that established Jim Crow. Second, the decline of lynching occurred because of both social and economic pressures. White Southerners desperately sought to recruit new industries and worked to deter racialized violence that may prevent companies from moving to their cities. Third, the “Double V” campaign of World War II was important, but the real postwar spark for the coming Civil Rights Movement was actually rooted in Black economic growth.

Hattiesburg is as innovative in its methodology as it is in its lessons. The African American narratives is largely a product of digital access to newspapers and census records. Because African Americans were excluded from local newspapers and archival repositories, Black people who lived in the Jim Crow South are harder to trace than their white counterparts. The historical records themselves are literally segregated. But Black citizens left records elsewhere. Hattiesburg uses oral histories and digitally available materials to track the activities and movements of local African Americans. It marshals much of this history through the family of Turner and Mamie Smith, who were local leaders in town and raised prominent children. It was people like them and their peers who built the churches that later housed the Freedom Schools in 1964.

Chapter 2, in particular, would be useful in a methods class, as it recreates the journey of Turner Smith from slavery to sharecropping and then ultimately into Hattiesburg. This journey is derived from two oral histories with his son and a careful tracing of his documentary record in census records and the Indianapolis Freeman, where local African Americans sent updates from their community. Turner’s path is cast against the backdrop of Emancipation, Reconstruction, Redemption, and then the rise of the New South. It shows how these major developments affected the destinies of people like Turner and Mamie Smith as they pursued their hopes and dreams amidst a rapidly changing society. More than just an overview of the Smith family saga, Chapter 2 provides a lesson in how to reincorporate marginalized peoples into the fabric of American history.

Ultimately, Hattiesburg is a book that intimately weaves the story of local Black and white communities into the fabric of life in the modern American South. It uses Hattiesburg as a lens, or even a character, if you will, to tell an important story of race and power, of opportunity and control, and of negotiation and consequence that enhances our historical understanding of life in the Jim Crow South.

Thanks for the information and the memories! My family moved to Hattiesburg when I was in the 7th grade. I lived there until 1982. As a psychologist I worked for the public schools for many years. Now, looking back, there was boundless energy involving change.